Freezing People is (Not) Easy (26 page)

Read Freezing People is (Not) Easy Online

Authors: Bob Nelson,Kenneth Bly,PhD Sally Magaña

The second day was another marathon of singing, posing, and professional dancers. About noon, Penny rather unceremoniously hollered across the room, “Bob, she's yours now.” I will remember that sentence forever as one of life's finest.

At six o'clock on the second evening, we finished our Herculean wedding. This princess would be coming home with me. What a joy! That night we attended a ball in our honor with over three hundred people joining in the celebration of our union. It was a spectacular eight-course feast of fried rice with shrimp, vegetables, whole carp, soup, and a wider variety of fruit than a farmers' market.

It wasn't long before someone asked to see us kiss.

“Finally,” I said, “we will share our first kiss.” As I took her in my arms for the first time, I closed my eyes and readied myself. I was once again frustrated when my lips touched the side of her cheek. She had turned her head at the last second. Everyone at the table laughed hysterically at my disappointment.

People at the next table again asked to see us kiss; this time I put my hand under her chin and guided her lips to meet mine. Time stopped in that magical moment. It was done. We had made it all come true just like she wanted, and now my ravishing wife would come to our home.

Over the past twenty-two years, Moeurth and I have enjoyed a marriage of love and respect without a single fight. We have brought two wonderful half-Italianâhalf-Cambodian girls into the world. We have certainly had disagreements, but through our deep admiration, we have managed to resolve them with calm consideration for each other. Only once did we come close to angry words over parental control of our two daughters. After I strongly had my say, Moeurth looked at me with a tear rolling down her cheek and then walked away without saying a word. I of course was brought to my knees by that tear and profusely apologized.

There was one exception during my twenty-five-year hiatus from the world of cryonics. I had left the cryonics movement without offering any justification, so in 1991 I granted Mike Perry, historian for the Alcor Foundation, and his two associates a forty-five minute interview.

I had never mentioned my cryonics past to my wife, and I felt I owed her that explanation after we had been married one year. She was intrigued by my past but not bothered. Compared to surviving a Pol Pot concentration camp in Cambodia and adjusting to American life, my delay in revealing this bit of history seemed minor to her.

Cryonics was beyond Moeurth's ability to understand. She was confused and I dare say frightened by the concept. She had seen so much death in her life and couldn't comprehend how a person might possibly come back. She often said, “Honey, me no want freeze, OK?” I always chuckled under my breath and replied, “Okay, darling, don't worry; I won't freeze you.”

Almost two decades later, I decided to write my story. Word had gotten to Sam Shaw, a producer for

This American Life,

and I agreed to an interview

.

Shortly afterward, Moeurth came to me and said, “Honey I have something to say. Please listen clearly. After many years of consideration and learning, now I want freeze. Now I understand.”

Chapter 18

Ted WilliamsâThe Story of One Recent Suspension

When news broke that beloved baseball player Ted Williams

had been cryonically preserved, I watched the Williamses' family drama unfold from the sidelines, still in self-imposed exile from cryonics. I was amazed by how far the technology had advanced in those years, yet the ensuing controversy was eerily familiar.

For more than thirty-five years, the cryonics movement had been hoping for famous individuals to choose cryopreservation. Prior to Ted Williams, perhaps the most famous cryopatient had been Richard “Dick Clair” Jones. Jones was a TV scriptwriter and producer for several shows, including

The Facts of Life, Flo,

and

Mama's Family,

and had won three Emmy awards for

The Carol Burnett Show.

Jones left some two million dollars to Alcor when he was cryopreserved in 1988. On July 5, 2002, Ted Williams was declared clinically dead and cryopreserved. As with so many other cryonic suspensions, controversy swirled around the case.

In 1996 Williams had signed a will stating that he wished to be cremated and his ashes scattered over the ocean off the Florida coast, where he'd been an avid fisherman. But his son, John-Henry, had become interested in cryonics. He had studied the literature and spoken with experts, and he wanted his famous father preserved in “biostasis”âcryopreservedâfor possible later reanimation. As an indication of the love between father and son, Ted had given his son power of attorney over his estate. At that time, both John-Henry and his sister, Claudia, were named as beneficiaries in the will. A child of an earlier marriage, Barbara Joyce “Bobby Jo” Ferrell, had become estranged from her father and was excluded.

When Ted Williams was close to the end of his life, John-Henry called the Alcor Foundation from the Florida hospital. John-Henry requested that the Alcor recovery team come to Florida at once. A private airplane was on standby to fly Williams from Florida to Scottsdale. The operating room and surgical team at Alcor were on full alert, waiting for the patient's arrival. The private airport adjacent to the Alcor facility brought Williams's body to within a few minutes' drive of Alcor's front door.

As with all cryonic suspensions, rapid action is vital, and Alcor was ready. On July 5, 2002, at 2:10 p.m., the great Ted Williams's heart stopped beating and he was pronounced clinically dead. At once the Alcor team took over and introduced a cooling agent through the carotid artery, while a heart-massaging machine maintained Williams's heart at a normal rhythm. The objective was to reestablish circulation and cool the brain as fast as possible while lowering the entire body temperature.

His body was released by hospital officials and rushed by emergency medical vehicle to the waiting jet, which promptly headed for Arizona. As the plane landed in Scottsdale, the medical team prepared Williams for the transfer to the waiting ambulance, which soon delivered him to the Alcor operating room.

Once he was on the table, the medical team took over preparing the body, shaving his head and adjusting tubes and valves. After about thirty minutes of preparation, they began to surgically remove, or “isolate,” the head, having first obtained John-Henry's approval. This step was controversial to many in cryonics, including Professor Ettinger, especially since this was a whole-body preservation, which some interpreted as an “

intact

whole body.” The surgical isolation was intended to optimize perfusion or infusion of cryoprotectant into the brain via the neck arteries.

As the seat of consciousness, feeling, memory, and selfhood, the brain is the all-important part of the anatomy for future recovery of a person. By optimizing the cryoprotection of the brain, the doctors could achieve a new, high level of preservation known as vitrification. As the patient was cooled to cryogenic temperatures, vitrification would prevent the formation of damaging ice crystals as cooling progressed. In this way, the quality of preservation is greatly improved over earlier techniques, further raising hopes that eventually the patient can be recovered in a healthy state. Such recovery would involve treating any ailments, including aging, and of course reattaching the head to the rest of the preserved body with all connections of blood vessels, nerves, and other structures restored.

At the time, cryopreservation techniques did not permit vitrification of the whole body, so the rest of the body, or trunk, was perfused by another method, and both head and trunk were cooled to cryogenic temperatures. For a while the head was stored at about -130°C in a low-temperature refrigeration unit known as the Cryostar, and then both head and body were transferred to an upright capsule and submerged in liquid nitrogen.

Controversy boiled up even as Ted Williams was undergoing the careful preparations at Alcor. Bobby Jo, the estranged daughter, insisted that her father be cremated as requested in his 1996 will. Meanwhile, John-Henry produced a document he had retrieved from the trunk of his car dated November 2, 2000, and signed by himself; his father, Ted; and his sister, Claudia. The note indicated their agreement “to be put into Bio-Stasis after we die. This is what we want, to be able to be together in the future, even if it is only a chance.” The document, if proven genuine, would supersede the request in the will for cremation. Two different testing labs determined the signature of Ted Williams to be genuine. The analysis also determined that Ted and John-Henry used the same pen, while Claudia used a different one. Claudia testified in a sworn affidavit to the note's authenticity.

Regardless of these results, Bobby Jo claimed the note was a forgery and did not negate the cremation request. She agreed to accede to her father's wishes in exchange for a settlement from the estate amounting to several hundred thousand dollars. Ted Williams remains in suspension and was joined at Alcor by his son when he died of leukemia in 2004.

Ted Williams's procedure of a whole body suspension should not be confused with another option as a final effort to save the patient: to recover only the head and allow the rest of the body to go. The rationale is that the brain is the important part and that head-only, or “neuro,” preservation might be sufficient to recover the entire patient someday, when the rest of the body could be replaced by advanced means of tissue and organ regeneration. Preserving just the head would save greatly on maintenance expenses and might have made it possible to stretch CSC's meager funds enough that some or all of the suspensions could have been continued.

I learned much later that Ev Cooper had written about neuro-Âpreservation (head only) in the 1960s, but it was not much considered, if at all, in the early years. The idea of decapitation is morbid and profoundly associated with the very worst of circumstances; of course people didn't want to think about it. If they did consider it, people questioned whether the body could be replaced as hoped, whether the result would still be the original person, and so on. I don't remember that neuro-preservation was ever discussed until after the capsule failures, when it was too late. If we had, I shudder to think how Nothern would have exploited decapitation at our trial. No one was neuro-preserved before Alcor's first suspension in July 1976, and the practice is still controversial. None of those I froze had expressed a wish for a neuro option, or to be converted to it should the funds run short. None of the relatives told me they wanted it performed as a way of either reducing expenses for their loved ones or continuing a suspension if it otherwise had to be terminated. During my years of involvement, we never tried or even considered the head-only option.

The struggle among Ted's children over what evidently amounted to money proved stressful to those in cryonics, because the procedures designed for optimum care seemed morbid to the public. In addition to the head being isolated, the skull was drilled with small openings, or burr holes, to observe the brain during the perfusion process. During the later cool-down to cryogenic temperatures, an apparatus detected sound bursts, indicating small hairline cracks formed in the solidified tissue, as normally occurred. These cracks too must be repaired by future technology, but in terms of loss of information, they are believed to be quite minor. Larry Johnson, an Alcor employee, leaked confidential information to the media in violation of the wishes of John-Henry and Claudia. A legislative initiative was started to restrict or eliminate cryonics in Arizona. In the end, this effort failed, and things returned to normal as media attention subsided. Cryonics in Arizona and elsewhere continues much as before. The wry observation was made that perhaps one day Ted Williams can confirm his real wishes and whether he is satisfied with how things finally turned out.

As of July 2013, numerous celebrities and millionaires have made covert arrangements for themselves. There are about 250 people currently in suspended animation; and well over a thousand people like you and me are all signed up, waiting for a time capsule ride into the future.

When we consider how far the science of human suspended animation has already advanced, we have vast reason to embrace a sublime, greatly extended life on the beautiful planet we call Earth.

Chapter 19

The Conclusion

The underlying Reality has cloaked itself in the ceaselessly transforming cosmos, declaring itself without revealing itself. The purpose of each soul's sojourn on earth is to learn to see beyond the evanescence of phenomena to the Eternal Reality.

âParamahansa Yogananda

Â

By far this is the most exciting chapter to write.

Why? For me the conclusion is really the beginning. In fact, the entire goal of cryonics is to delay any ending by hundreds of years. Thinking back on my epic near-fifty-year cryonics journey, I can honestly say most of it was an honor and only a small part of it was a nightmare.

As a devoted advocate of cryonics during that heady ten-year period, I was president of the Cryonics Society of California and seized the opportunity to freeze the first man, first woman, and first child. As one of the movement's most prolific spokesmen, I taught people about this optimistic new science in numerous interviews and TV shows, including interviews with Regis Philbin and Phil Donohue. Through those years, I had an incredible journey.

Dr. Bedford has been suspended for more than forty-five years, and he is still only minutes into the dying process. If all goes well, he will remain in this stage of early clinical death for centuries if need be, until science determines his fate. Even if there is no hope for this man, he has taken the first step in humanity's search for extended life. It was easy for later cryonics activists to criticize our actions in those first days. During Dr. Bedford's suspension, we did not have a cooperating mortuary or even a sympathetic mortician.

The story of Dr. Bedford's freezing appeared in the first six pages of

Life

magazine's February 3, 1967, issue. I was excited about the potential exposure. An interesting but unfortunate aside is that for only the second time in its history, after two million copies of the issue had been printed and mailed to subscribers,

Life

stopped the presses. The first nine pages were replaced with the story of Grissom, White, and Chaffee, the three

Apollo 1

astronauts who died when their capsule caught fire during a pre-launch test. Consequently, our article was scrapped. The only other time

Life

axed a story was after the Kennedy assassination.

I had first become interested in cryonics because I knew that suspended animation was the best way to make long-distance spaceflight possible. I mourned the loss of those astronauts and pioneers, and yet I was confident that unfortunate tragedy and failure would not prevent future manned spaceflight. On the now-retired launchpad where the

Apollo 1

explosion occurred, one of the memorial plaques states:

Â

In memory of those who made the ultimate sacrifice so others could reach for the stars;

Ad astra per aspera

(A rough road leads to the stars)

Â

The next ten years did not proceed like that early success; instead I spent them like I was hanging on to the side of a mountain by my fingernails. I had dedicated myself to making cryonic suspension available to Americans at the end of their life. However, my great project suffered a long, slow death. After acquiring nineâand losing sevenâfrozen bodies, I had to give up.

After losing my friends and after my abject failure with the vault, the lawsuits that recast my motives in the worst possible way were a devastating sucker punch. With such horrendous charges being made against Joseph Klockgether and me, everyone involved with cryonics might have run and hidden. With the exception of the CSC's secretary, Paul Porcasi, who feared his name being mentioned, every other officer, friend, and neighbor of the Cryonics Society voluntarily took the stand on our behalf. A few years later I received some sense of justice when that snake Worthington was disbarred, partly because of my case.

I spent the next twenty-five years in self-imposed exile from cryonics. I was largely silent and allowed other people to castigate and vilify me, fairly or not, as creating a “black stain” on cryonics. I haven't told my full story to correct history . . . until here and now.

But God chose differently, and this story did not end on such a sour note. I kept my promise for twenty-five years, staying largely silent as other people rewrote the history of what happened at the Chatsworth cemetery, and unfortunately I gave unspoken credence to the horrendous judgment against me. Today the cemetery owners deny they ever heard of cryonics and that a cryonics vault was ever built there. However, the location is still visible, and currently at least seven people are interred in the CSC underground vault there.

Eventually I came out of my self-induced coma to once again embrace cryonics. I was close to retirement and itching to write this book, mostly for my children. I called Professor Ettinger, and he gave his approval, saying, “I always know where your heart is.”

After those years, I've acquired some perspective on CSC's contributions to cryonics. We propelled the cause forward by years when we froze Dr. Bedford. The CSC was the first to implement the Anatomical Gift Act, which is still used by cryonics organizations today. Even our failures, as with all young sciences, had beneficial effects by illustrating mistakes to be avoided in the future.

This subject has always been sensational and attracted high demand for debate and conflict. Many conservative scientists today believe that reanimation will never succeed. However, I prefer to focus on tomorrow's anticipated achievements rather than the limited means of today. Of course we realize it is not possible now to reanimate a frozen humanâthe consideration is about tomorrow!

Today I know differently from my beliefs during those invigorating days of early optimism. Just as the science evolves, so too must our human perceptions for scientific breakthroughs to succeed. Advance any controversial theory that attracts the attention of the popular media or religious leaders and isn't fully proven, and most scientists or the bureaucratic infrastructure will inundate the pioneers with reasons it will never work. Science, like nascent countries and philosophies, needs cowboys and revolutionaries, but unfortunately the rigors of the scientific method, while certainly necessary, can squelch discovery before it advances from hypothesis to experiment.

The truth is, no one can say with certainty what the future will bring. The distant future of one or two centuries

cannot be known

by anyone alive today! A cave dweller might well say “Man can never fly,” but it takes people of vision to see beyond the darkness of their cave. Men whose vision we take for granted, such as Arthur C. Clarke, said cryonic suspension will someday be just another choice of interment.

In 2004 I received an invitation to visit the Alcor cryonics facility in Scottsdale, Arizona, and I visited my old friend, Dr. James Bedford. I was in awe of Alcor and what they had accomplished since I had walked away from cryonics in 1981. The management treated me like royalty, and I was deeply honored. When I was shown Dr. Bedford's capsule, I embraced it. Thirty-seven years had passed since I had last seen him, and this was an emotional reunion.

The next year, I was tentatively reentering the cryonics world while visiting the state-of-the-art cryonic storage facilities at the Cryonics Institute in Clinton Township, Michigan. I was happy to talk with the former CSNY president, Curtis Henderson, at the home of Professor Ettinger. We hadn't seen each other for twenty years. Curtis was gracious, but I could sense that he had some passion in his heart, and I encouraged him to spit it out. That was the reason I had traveled to this meeting. I thought to myself,

If anyone wants to say something or ask me somethingâsay it to my face. Here I am, let it be now.

Curtis told me that I had undermined the cryonics movement. He said that once a leader of a cryonics group had accepted responsibility for suspending patients, he had a sacred duty to allow nothing to get in the way of keeping those patients in suspension forever. There was absolutely no acceptable excuse for not doing so, none whatsoever.

When he finished, I asked him, “If what you said is true, then can you please explain the suspension patients at the CSNY facility? They eventually had the same fate as every CSC patientâbeing buried or cremated.”

Curtis looked at me as though I had just hit him in the head with a baseball bat. He sat staring at me, not saying a word, thinking I know not what.

After a good fifteen minutes of just staring at me, he got up and went into his bedroom. I was unsure what was going to happen. Curtis reappeared a half hour later, and we spent the next couple of days being very cordial and respectful to each other. He was a true pioneer, trying to keep the patients at his New York facility in suspension. We did the very best with what we had; however, we both reached a point when

without money

we could go no further.

On my last visit to the Michigan facility, after I had completed all my legal and financial arrangements for my own cryonic suspension, I was privileged to witness an unforgettable moment in the main storage area where ten huge cryogenic capsules are under twenty-four-hour surveillance, each holding eight patients in liquid nitrogen.

In this room full of enormous, pure-white, human cryogenic containers stood a petite, lovely lady named Bridgett. She walked up to one of these gigantic vessels, placed her face on the resin-fiberglass with her arms outstretched, hugging the enormous unit, and said, “I'm here, darling, and I'll join you when my time comes. Please know that I love you with all my heart!”

With everything said and done, I stand before the world and future generations with a clear conscience and an open heart. I accept my lumps for my dumb mistakes. To the best of my recollection, this is exactly how it happened. And my sole purpose for writing this book is to leave a sincere accounting of my journey.

As Dr. Bedford told me the day before his body was frozen more than forty-five years ago, I repeat here today: If I am never to be resuscitated, I do this so my children and grandchildren might participate in the wonders of science and future medicine.

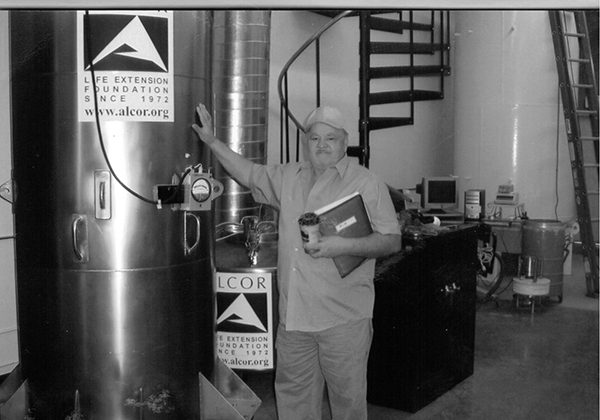

Bob Nelson stands next to the dewar containing Dr. James Bedford.

One summer day in July 2011, I was struck by an odd sense of foreboding and phoned Professor Ettinger. I eventually reached a nurse who told me he was in a coma and near clinical death. I pleaded with her to let me know if he regained consciousness. Two years earlier, after my

This American Life

interview, I had been approached by Hollywood producers and directors about filming my life story. I had just heard some exciting news about the cryonics movie and wanted Professor Ettinger to know. The actors had been chosen, and the film's production seemed assured. After his death, I received this e-mail from his daughter-in-law.

Â

Bob was made aware, in his final hours, of your call and of the impending movie, which made him smile, very possibly his last smile. He was a brave, brilliant visionary. He got the best suspension that preparation, attention to detail, and love could get him. If there is a sequel to this life, I'm sure he will be in it.