From The Holy Mountain (15 page)

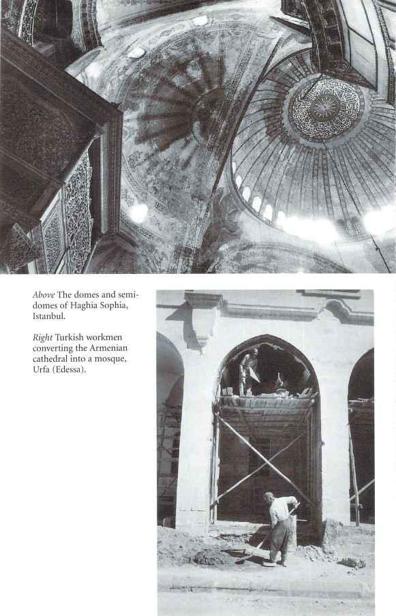

'No,' he said. 'Armenian.'

'Are there any Armenians left in Urfa?'

'No,' he said, smiling broadly and laughing. His friend made a throat-cutting gesture with his trowel.

'They've all gone,' said the first man, smiling. 'Where to?'

The two looked at each other: 'Israel,' said the first man, after a pause. He was grinning from ear to ear. 'I thought Israel was for Jews,' I said.

'Jews, Armenians,' he replied, shrugging his shoulders. 'Same thing.'

The two men went back to work, cackling with laughter as they did so.

H

otel

K

aravansaray

,

D

iyarbakir

,

16

A

ugust

A bleak journey: mile after mile of blinding white heat and arid, barren grasslands, blasted flat and colourless by the incessant sun. Occasionally a small stone village clustered on top of a tell. Otherwise the plains were completely uninhabited.

Diyarbakir, a once-famous Silk Route city on the banks of the River Tigris, was announced by nothing more exotic than a ring of belching smokestacks. The old town lies to one side, on a steep hill above the Tigris. It is still ringed by the original Byzantine fortifications built by Julian the Apostate in the austere local black basalt, and their sombre, somehow unnatural darkness gives them a grim and almost diabolic air.

The Byzantines knew Diyarbakir as 'the Black', and it has a history worthy of its sinister fortifications. Between the fourth and seventh centuries it passed back and forth between Byzantine, Persian and Arab armies. Each time it changed hands its inhabitants were massacred or deported. In 502

a

.

d

. it fell to the Persians after the Zoroastrian troops found a group of monks drunk at their posts on the walls; after the subsequent massacre, no fewer than eight thousand dead bodies had to be carried out of the gates.

Today the city retains its bloody reputation. It is now the centre of the Turkish government's ruthless attempt to crush the current Kurdish insurgency, and indeed anyone who speaks out, however moderately, for Kurdish rights. In Istanbul journalists had told me that Diyarbakir crawled with Turkish secret police; apparently in the last four years there have been more than five hundred unsolved murders and 'disappearances' in the town. One correspondent said that shortly after his last visit, the editor of a Diyarbakir newspaper who had given him a slightly outspoken interview had an 'accident', tumbling to his death from the top floor of his newspaper offices; after this the political atmosphere became so tense that local newspapers could only be bought from police stations. No one, said the journalist, dared to speak to him, other than one shopkeeper who whispered the old Turkish proverb: 'May the snake that does not bite me live for a thousand years.'

As we drove, I wondered if my taxi driver would prove equally tongue-tied, so I asked him if things were still as bad as they had been. 'There is no problem,' he replied automatically. 'In Turkey everything is very peaceful.'

As we passed along the black city walls, I noticed a crowd gathering on the other side of the crash-barrier. Armed policemen in flak jackets and sunglasses were jumping out of jeeps and patrol cars and running towards the crowd. I asked the driver what was happening. He pulled in and asked a passer-by, an old Kurd in a dusty pinstripe jacket. The two exchanged anxious words in Kurdish, then he drove on.

"What did he say?'

'Don't worry,' said the driver. 'It's nothing.' 'Something must have happened.'

We pulled up in front of a huge green armoured car that was parked immediately in front of my hotel; from the top of its glossy metallic carapace protruded the proboscis of a heavy machine gun.

'It's nothing,' repeated the driver. 'The police have just shot somebody. Everyone is calm. There is no problem.'

That evening I found my way through back alleys to Diyarbakir's last remaining Armenian church.

In the mid-nineteenth century the town had had one of the largest Armenian communities in Anatolia. Like the Jews of Eastern Europe, the Armenians ran the businesses, stocked the shops and lent the money. Like the East European Jews, their prominence led to resentment and, eventually, to a horrific backlash.

In 1895, during the first round of massacres, 2,500 Armenians were clubbed to death, shut up in their quarter like rabbits in a sealed burrow. When the English clergyman the Rev. W. A. Wigram visited the town in 1913 he reported seeing 'the doors still