Frozen in Time (7 page)

Ironically, Franklin's failure launched the golden era of Arctic exploration. More than thirty ship-based and overland expeditions would search for clues as to Franklin's fate over the course of the following two decades, charting vast areas and mapping the completed route of the Northwest Passage in the process. Whilst many of these search expeditions were funded by the British government in response to public demand that Franklin be saved, others were raised by public subscription following appeals from Lady Franklin. Seamen volunteered for Arctic service in droves. Yet contemporary journals make it clear that many of these searches were also crippled by illness. In this respect, James Clark Ross was not alone.

Indeed, there was a more sinister enemy on board these Arctic voyages than the usual complaints of frostbite and stiï¬ing boredom. Where one captain, George Henry Richards, reported the “general debility” afflicting his crew, another, Sir Edward Belcher, abandoned four of his ï¬ve ships in order to escape the far north after two years, fearing that a third Arctic year would lead to large-scale loss of life. The crew of another ship, the

Prince Albert,

a privately funded expedition, suffered severely from scurvy during their lone winter, 1851â52. And on the

Enterprise,

Captain Richard Collinson waged a bitter internecine war with his crew; by the end of his command he had placed, amongst others, his ï¬rst, second and third officers under arrest. When he was subsequently criticized for his conduct, Collinson blamed “some form of that insidious Arctic enemy, the scurvy, which is known to effect the mind as well as the body of its victims.”

When another ship, the

Investigator,

commanded by Captain Robert McClure, became trapped at Mercy Bay on Banks Island, several of the men aboard went mad and had to be restrained, their howls piercing the long nights. The crew carried lime juice, specially prepared by the Navy's Victualling Department, and hunted and gathered scurvy grass in the brief Arctic summers. By these methods, McClure was able to forestall the appearance of scurvy, but by the third winter, illness was widespread: “only 4 out of a total of 64 on board were not more or less affected by scurvy.” Alexander Armstrong, expedition surgeon, described treating sufferers with “preserved fresh meat,” as tinned foods were still considered to have antiscorbutic properties. Even after such interventions, three of the men died. McClure abandoned ship, and his crew were spared only by a fortuitous encounter with yet other search ships. Thomas Morgan, who was seriously ill at the time of this rescue, “sick and covered with scurvy sores,” died on 19 May 1854. He was buried on Beechey Island, alongside the men from the

Erebus

and

Terror.

Yet McClure, who was credited with the ï¬rst successful transit of the Northwest Passage, even without his ship, was glad for the struggle he had been put through. He, like others of the age, saw self-sacriï¬ce in some noble cause as the pinnacle of human achievement. He captured the spirit of the Franklin searchers this way:

How nobly those gallant seamen toiled⦠sent to travel upon snow and ice, each with 200 pounds to drag⦠No man ï¬inched from his work; some of the gallant fellows really died at the drag rope⦠but not a murmur arose⦠as the weak fell out⦠there were always more than enough volunteers to take their places.

By far the worst afflicted, however, were two Franklin search expeditions funded by Henry Grinnell, a wealthy American benefactor. The ï¬rst, commanded by Lieutenant Edwin de Haven of the U.S. Navy, aboard the

Advance

and the

Rescue,

went out in May 1850 and by August was already trapped in winter quarters with temperatures plummeting. Elisha Kent Kane, the ship's surgeon and the scion of a wealthy Philadelphia family, described the appalling living conditions endured by the crew:

⦠within a little area, whose cubic contents are less than father's library, you have the entire abiding-place of thirty-three heavily-clad men. Of these I am one. Three stoves and a cooking galley, three bear-fat lamps burn with the constancy of a vestal shrine. Damp furs, soiled woolens, cast-off boots, sickly men, cookery, tobacco-smoke, and digestion are compounding their effluvia around and within me. Hour by hour, and day after day, without even a bunk to retire to or a blanket-curtain to hide me, this and these make up the reality of my home.

A pervasive melancholy set in, and scurvy made its ï¬rst appearance in September. By Christmas, there was a general shortness of breath, and the officers noticed a strange phenomenon that the British searchers had also identiï¬ed, “a sort of craving” for animal fats. Kane described the complexions of the crewmen as having assumed a “peculiar waxy paleness,” even “ghostliness.” The men reported outlandish, vivid dreams. One described ï¬nding “Sir John Franklin in a beautiful cove, lined by orange-trees.” Another dreamt he had visited the desolate nearby coast and “returned

laden with watermelons.” By January, de Haven was also stricken and forced to relinquish command. Among other complaints, he suffered severe pain from a wound in his hand inï¬icted by a schoolmaster's ruler twenty-ï¬ve years before. In February, twelve men were laid out by stiff and painful limbs. Largely dependent on salted and preserved foods, the crew's stores of antiscorbutics, raw potatoes and lime juice were running low. In May, the crew succeeded in killing a large number of seals and walrus, and catastrophe was averted.

The second Grinnell expedition, this time commanded by Elisha Kent Kane, sailed in 1853 with instructions to search Smith Sound, ostensibly for Franklin's missing ships. The expedition was, in fact, a thinly veiled run at the North Pole. This was his ï¬rst command, and Kane was hardly the image of a grizzled Arctic explorer. Of sickly, almost dainty, constitution, he made up for his physical limitations with the spirit of a dauntless adventurerâhis account of this journey is infused with romanticism. He relished the Arctic as a “mysterious region of terrors” as he tacked north through Smith Sound into an unexplored basin that now carries his name. Here, the crew established a winter harbour off the coast of Greenland and lived in a state of perpetual misery. Kane was right with respect to one thing: the terrors abounded. The ship was not insulated, and Kane had miscalculated on the amount of fuel required. By February they could no longer spare fuel to melt water to wash in. It was so cold inside the

Advance

that one man's tongue froze to his beard.

Dependent on “ordinary marine stores,” notably pemmican and salt pork, there was also a severe outbreak of scurvy among the twenty men. Kane carefully noted the advance of symptoms. In February 1854, he wrote, “scurvy and general debility have made me short o' wind.” In April, Kane dispatched his sledging parties north towards the pole. It was a foolhardy gambit that soon degenerated, the party stricken with frostbite and scurvy. The illness that had gnawed at them all winter now threatened to consume them entirely. Kane himself had to be carried back to the

Advance,

“nearly insensible and so swollen with scurvy as to be hardly recognizable.” His condition was regarded as hopeless. When the party reached the ship they were in total disarray, suicidal, incoherent, disease-ridden, gesticulating wildly and conversing with themselves. The ship “presented all the appearances of a mad house.” There remained only three men well enough to carry out ordinary duties. To top it all, rats had infested the ship.

Fortunately, with summer's thaw, the hardships that had characterized the winter abated. Hunting parties were sent off and, with a large supply of fresh meat, health was soon restored. But the ice failed to clear from the ship's harbour, and the crew faced a second winter.

Under stress Kane proved to be unï¬t for command. He became irritable and quarrelsome, and when he wasn't picking an argument with one of his officers he was boasting about his family's status or his amorous conquests back in Philadelphia. His lengthy dinnertime monologues were liberally peppered with Latin phrases, all for the beneï¬t of men he considered his social inferiors. Sick and starved to the bone (on a good day eating the entrails of a fox, on a bad day sucking on their mittens), the crew looked on with a mixture of incredulity and contempt as their commander tried to impress them by speaking the ancient language. Soon, secret meetings were organized, and in September, seven of the men announced to Kane their intention to desert ship and attempt a 700-mile (1,126-km) trek south to Upernavik, the northernmost of Greenland's Danish communities. Yet the mutineers got nowhere near it before returning to the brig nearly frozen to throw themselves at Kane's mercy, which proved a shallow well indeed.

As the second winter set upon them they were nearly out of coal, and Kane ordered the men to use wood from the

Advance

for fuel. They tore off the deck sheathing and removed the ship's rails and upper spars. Unable to secure adequate supplies of raw meat in the fall, the disease returned even more virulently. The symptoms were gruesome. One man had the ï¬esh drop from his ankle, exposing bone and tendons. By December, the only antiscorbutics left were the scrapings of raw potatoes, but there were only twelve of the potatoes left and they were three years old. The entire crew was seriously ill, and Kane was surprised to discover their condition improved or worsened in exact relation to their infrequent ability to obtain fresh meat. Wrote Kane: “Our own sickness I attribute to our civilized diet; had we plenty of frozen walrus I would laugh at scurvy.” He later wrote admiringly of the Inuit: “Our journeys have taught us the wisdom of the Esquimaux appetite, and there are few among us who do not relish a slice of raw blubber or a chunk of frozen walrus-beef⦠as a powerful and condensed heat-making and antiscorbutic food it has no rival.”

Other searchers had come to the same realization, and one, the surgeon Peter Sutherland, suggested in 1852 that had Franklin needed to increase his stock of provisions, “there is no doubt his ingenuity would suggest to him what the Eskimos have practiced for thousands of yearsâpreserving masses of animal substances, such as whales ï¬esh, by means of ice, during the summer months, when it may be easily obtained, for their use during winter.”

The realization came too late for Kane. The health of the crew reached its worst in the spring of 1855, and several men died. At one point, Kane referred to his compatriots in his journal as “my crew,” then corrected himself, writing: “I have no crew any longer.” Instead, he began referring to the men as “the tenants of my bunks.” Kane was, at this point, effectively alone. Of the men on the expedition, only he had remained in comparatively good health throughout the second winter. The reason was simple: Kane had taken to eating the rats infesting the ship. Despite their privations, he could not convince any of the other men to join him.

In the spring, after acquiring fresh walrus meat with the help of some of the natives of Greenland who visited the ship, the bedraggled party abandoned the

Advance

and made its way down the coast, ï¬rst over the ice and then in small boats. After eighty-four days they ï¬agged down a Danish shallop and were saved. They had done nothing to advance the search for Franklin. In fact, they were some 1,000 miles (1,609 km) away from where the last remnants of the expedition were ï¬nally located.

By 1854 nine years had elapsed since Franklin set sail on his voyage of discovery. He had provisions for three years, though it was thought the supplies could have been rationed to last some months longer, perhaps until 1849. What became obvious to the Admiralty was that, regardless of what more could be done to solve the mystery, nothing could be done to save Franklin and his men. On 20 January 1854, a notice in the

London Gazette

stated that unless news to the contrary arrived by 31 March, the officers and crews of the

Erebus

and

Terror

would be considered to have died in Her Majesty's service, and their wages would be paid to relatives up to that date. The expedition's muster books show the sailors buried on Beechey Island, however, were “discharged dead” according to the dates on their headboards: William Braine on 3 April 1846, John Hartnell on 4 January 1846, John Torrington on 1 January 1846.

Despite the official acknowledgement that no more relief expeditions would be sent, interest in the Franklin searchâand in the Arctic in generalâremained high in Britain. Three Inuit (or “Esquimaux” as the Victorians called them) were taken to England by a merchant and given an audience with Queen Victoria at Windsor Castle, then “exhibited” in London. “The painful excitement which has so long pervaded the minds of all classes with respect to the fate of Sir John Franklin's Arctic Expedition lends additional interest to the examination of these natives of the dreary North,” the

Illustrated London News

commented. Interest among North Americans did not always match that of the British public's, however. In one instance, the

Toronto Globe

complained that only a handful of people attended a lecture on the Arctic and the possible fate of Sir John Franklin, while the same hall had been “ï¬lled to overï¬owing” with those curious to view the famous midget Tom Thumb.

Finally, on Monday, 23 October 1854, under the headline “Startling News: Sir John Franklin starved to death,” the

Toronto Globe

reported “melancholy intelligence” that had arrived in Montreal two days earlier. After his failed earlier investigations, the Hudson's Bay Company's John Rae had made the ï¬rst major discovery of the Franklin searches while surveying the Boothia Peninsula. The

Globe

excitedly outlined the news:

From the Esquimaux [Rae] had obtained certain information of the fate of Sir John Franklin's party who had been starved to death after the loss of their ships which were crushed in the ice, and while making their way south to the great Fish [Back] river, near the outlet of which a party of whites died, leaving accounts of their sufferings in the mutilated corpses of some who had evidently furnished food for their unfortunate companions.

Two days later, the

Globe

argued that Rae had succeeded “in revealing to the world the mysterious fate of the gallant Franklin and his unfortunate companions, and in proving the folly of man's attempting to storm âwinter's citadel' or light up âthe depths of Polar night.' ” By 28 October 1854, word had reached Britain that the veil that obscured the fate of Sir John Franklin had been lifted. In a letter to the Secretary of the Admiralty, Rae outlined his discoveries:

⦠during my journey over the ice and snow this spring, with the view of completing the survey of the west shore of Boothia, I met with Esquimaux in Pelly Bay, from one of whom I learned that a party of âwhitemen' (Kablounans) had perished from want of food some distance to the westward⦠Subsequently, further particulars were received, and a number of articles purchased, which place the fate of a portion, if not all, of the then survivors of Sir John Franklin's long-lost party beyond a doubtâa fate terrible as the imagination can conceive.

Rae went on to report descriptions of a party of white men dragging sledges down the coast of King William Island, of the discovery a year later of bodies on the North American mainland and evidence of cannibalism. Contrary to the

Toronto Globe

headline, there was no proof that Franklin himself had starved to death, but disaster had clearly befallen his crews. Evocatively, the Inuit also told Rae that “they had found eight or ten books where the dead bodies were; that those books had âmarkings' upon them, but they would not tell whether they were in print or manuscript.” When Rae asked what they had done with the books, possibly expedition logs, he was told that they had given them to their children, “who had torn them up as playthings.” In support of the Inuit accounts, Rae carried with him items he had been able to purchase from the natives, including monogrammed silver forks and spoons, one of them bearing Crozier's initials, and Sir John Franklin's Hanoverian Order of Merit.

Because Rae's information about the cause of the expedition's destruction came second-hand, it was judged inconclusive by many, though the relics were evidence enough that “Sir John Franklin and his party are no more.” The British government, enmeshed in the Crimean War, asked the Hudson's Bay Company to follow up on the new information. Its chief factor, James Anderson, was able to add only slightly to Rae's report when he discovered several articles from the Franklin expedition on Montreal Island and the adjacent coastline, including a piece of wood with the word “Terror” branded on it, part of a backgammon board and preserved meat tinsâbut no human remains or records. Anderson's search, which lasted only nine days, would be the last official attempt to learn the fate of Franklin. Rae, though attacked by critics for not following up on the Inuit reports and instead hurrying back to London, was given £8,000 in reward money; the men in his party split another £2,000.

The British public and government interest quickly turned to the Crimean War. The very week that news of Rae's discoveries reached Britain, a confusion of orders resulted in a brigade of British cavalry charging some entrenched batteries of Russian artillery. A report in the

Times

captivated Franklin's nephew, the poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson, who immortalized the encounter where so many British horsemen died in his “The Charge of the Light Brigade.” Events had ï¬nally overtaken the disappearance of Sir John Franklin and his officers and crews, leaving many to believe that the mystery of the expedition's destruction would never be solved. In addition, there were others who questioned the value of research expeditions such as Franklin's, which demanded such a heavy toll.

Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine

summed up this view better than any other journal in an article published in November 1855:

No; there are no more sunny continentsâno more islands of the blessedâhidden under the far horizon, tempting the dreamer over the undiscovered sea; nothing but those weird and tragic shores, whose cliffs of everlasting ice and mainlands of frozen snow, which have never produced anything to us but a late and sad discovery of depths of human heroism, patience, and bravery, such as imagination could scarcely dream of.

Yet there were still those who had not given up on Arctic expeditions, who still believed that the answers to Franklin's fate lay somewhere on King William Island or on the mainland close to the mouth of the Back River. Foremost among them was Lady Franklin, who made one last impassioned plea to British Prime Minister Lord Palmerston: “⦠the ï¬nal and exhaustive search is all I seek on behalf of the ï¬rst and only martyrs to Arctic discovery in modern times, and it is all I ever intend to ask.” She failed to convince the British government to send one ï¬nal search, and launched another expedition of her own. No longer seeking the rescue of Franklin, she now sought his vindication.

Jane, Lady Franklin, neé Griffin, aged twenty-four.

Lady Franklin, born Jane Griffin, personiï¬ed the romantic heroine with her refusal to give up hope that searchers would one day discover the fate of her husband and his crews. Her determination, coupled with a willingness to spend a large part of her fortune to outï¬t four such expeditions, haunted the Victorian public as much as it inspired the searchers of her day. “To

know

a loss is a single and deï¬nite pain,” the

Athenaeum

observed, “to dread it is a complicated anguish which to the pain of the fear adds the pain of the hope⦠The misery is, that if the truth be not known, Lady Franklin will nurse for years her frail hope, almost too sickly to live and yet unable to die.”

What makes the devotion of Lady Franklin especially moving is the recognition that she was an independent and free-thinking woman who had not married until her thirties, and who saw more of the world than possibly any other woman of her day. During her long vigil, Lady Franklin not only implored the British for help, but the president of the United States and the emperor of Russia as well. She became an expert in Arctic geography. One famous folk song, “Lord Franklin,” captured the passion of her search:

In Baffin's Bay where the whale-ï¬sh blow,

The fate of Franklin no man may know.

The fate of Franklin no tongue can tell,

Lord Franklin along with his sailors do dwell.

And now my burden it gives me pain,

For my long lost Franklin I'd cross the main.

Ten thousand pounds I would freely give,

To say on earth that my Franklin lives.

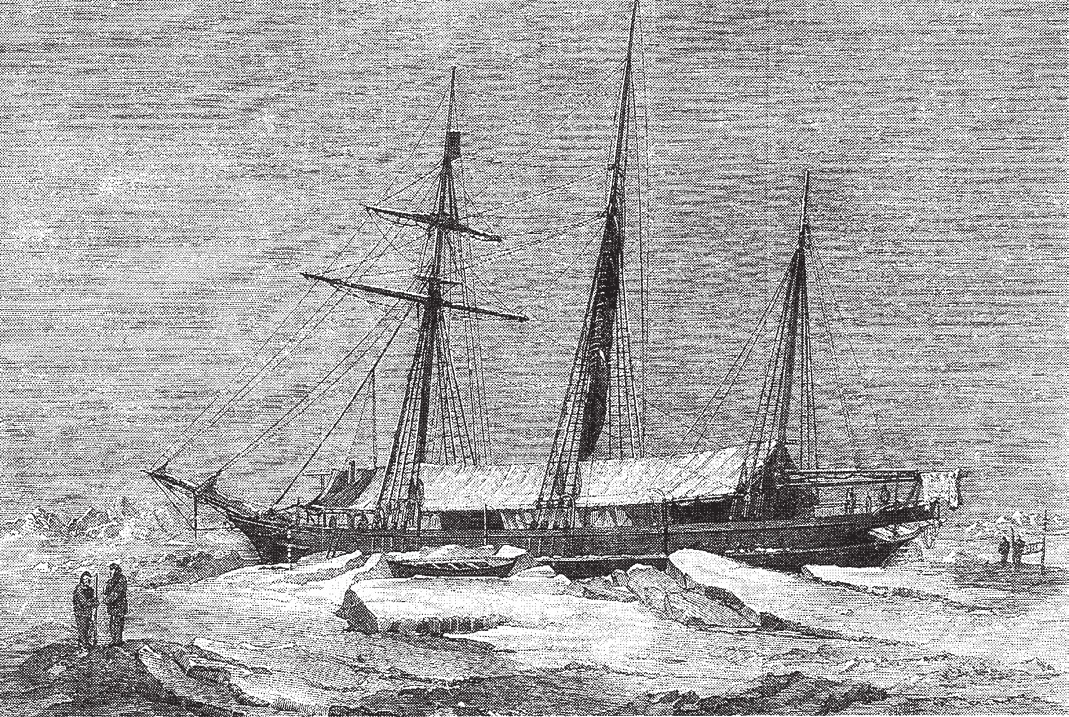

With the help of a public appeal for funds and a donation of supplies by the Admiralty, Lady Franklin purchased a steam yacht, the

Fox,

and placed command with the Arctic veteran Captain Francis Leopold M'Clintock, a Royal Navy officer who had been involved in three earlier Franklin search expeditions, beginning with that of James Clark Ross's attempt in 1848â49. M'Clintock chose Lieutenant William Robert Hobson, son of the ï¬rst governor of New Zealand, as his second-in-command. The

Fox

sailed from Aberdeen, Scotland, on 1 July 1857.

Almost immediately, problems hampered the search and the

Fox

was forced to spend its ï¬rst winter trapped in ice in Baffin Bay, before being freed in the spring. By August 1858 the

Fox

had reached Beechey Island, where, at the site of Franklin's ï¬rst winter quarters, M'Clintock erected a monument on behalf of Lady Franklin. The monument, dated 1855, read in part:

To the memory of Franklin, Crozier, Fitzjames and all their gallant brother officers and faithful companions who have suffered and perished in the cause of science and the service of their country this tablet is erected near the spot where they passed their ï¬rst Arctic winter, and whence they issued forth, to conquer difficulties or to die. It commemorates the grief of their admiring countrymen and friends, and the anguish, subdued by faith, of her who has lost, in the heroic leader of the expedition, the most devoted and affectionate of husbands.

By the end of September the searchers had travelled to the eastern entrance to Bellot Strait, where they established a second winter base. From there, M'Clintock and Hobson were able to leave their ship in small parties and travel overland to King William Island, early in April 1859. The two groups then split up, with M'Clintock ordering Hobson to scour the west coast of the island for clues while he travelled down the island's east coast to the estuary of the Back River, before returning via the island's west coast.

On 20 April, M'Clintock encountered two Inuit families. He traded for Franklin relics in their possession and, upon questioning them, discovered that two ships had been seen but that one sank in deep water. The other was forced onto shore by the ice. On board they found the body of a very large man with “long teeth.” They said that the “white people went away to the âlarge river,' taking a boat or boats with them, and that in the following winter their bones were found there.” Later, M'Clintock met up with a group of thirty to forty Inuit who inhabited a snow village on King William Island. He purchased silver plate bearing the crests or initials of Franklin, Crozier and two other officers. One woman said “many of the white men dropped by the way as they went to the Great River; that some were buried and some were not.”

The Fox,

trapped in Baffin Bay in 1857â58.

M'Clintock reached the mainland and continued southward to Montreal Island, where a few relics, including a piece of a preserved meat tin, two pieces of iron hoop and other scraps of metal, were found. The sledge party then turned back to King William Island, where they searched along its southern, then western coasts. Ghastly secrets awaited both M'Clintock and Hobson as they trudged over the snow-covered land.

Shortly after midnight on 24 May 1859, a human skeleton in the uniform of a steward from the lost expedition was found on a gravel ridge near the mouth of Peffer River on the island's southern shore. M'Clintock recorded the tragic scene in his journal:

This poor man seems to have selected the bare ridge top, as affording the least tiresome walking, and to have fallen upon his face in the position in which we found him. It was a melancholy truth that the old woman spoke when she said, “they fell down and died as they walked along.”

M'Clintock believed the man had fallen asleep in this position and that his “last moments were undisturbed by suffering.”

Alongside the bleached skeleton lay a “a small clothes-brush near, and a horn pocket-comb, in which a few light-brown hairs still remained.” There was also a notebook, which belonged to Harry Peglar, captain of the foretop on the

Terror.

The notebook contained the handwriting of two individuals, Peglar and an unknown second. In the hand of Peglar was a song lyric, dated 21 April 1847, which begins: “The C the C the open C it grew so fresh the Ever free.” A mystery, however, surrounds the other papers, written in the hand of the unknown and referring to the disaster. Most of the words in the messages were spelled backwards and ended with capital letters, as if the end were the beginning. One sheet of paper had a crude drawing of an eye, with the words “lid Bay” underneath. When corrected, another message reads: “Oh Death whare is thy sting, the grave at Comfort Cove for who has any douat how⦠the dyer sad⦠” On the other side of that paper, words were written in a circle, and inside the circle was the passage, “the terror camp clear.” This has been interpreted as a place name, a reference to a temporary encampment made by the Franklin expeditionâpossibly the encampment at Beechey Island. Another paper, written in the same hand, also spelled backwards, includes this passage: “Has we have got some very hard ground to heave⦠we shall want some grog to wet houer⦠issel⦠all my art Tom for I do think⦠time⦠I cloze should lay and⦠the 21st night a gread.” The “21st night” could be 21 April 1848, the eve of the desertion of the

Erebus

and

Terror

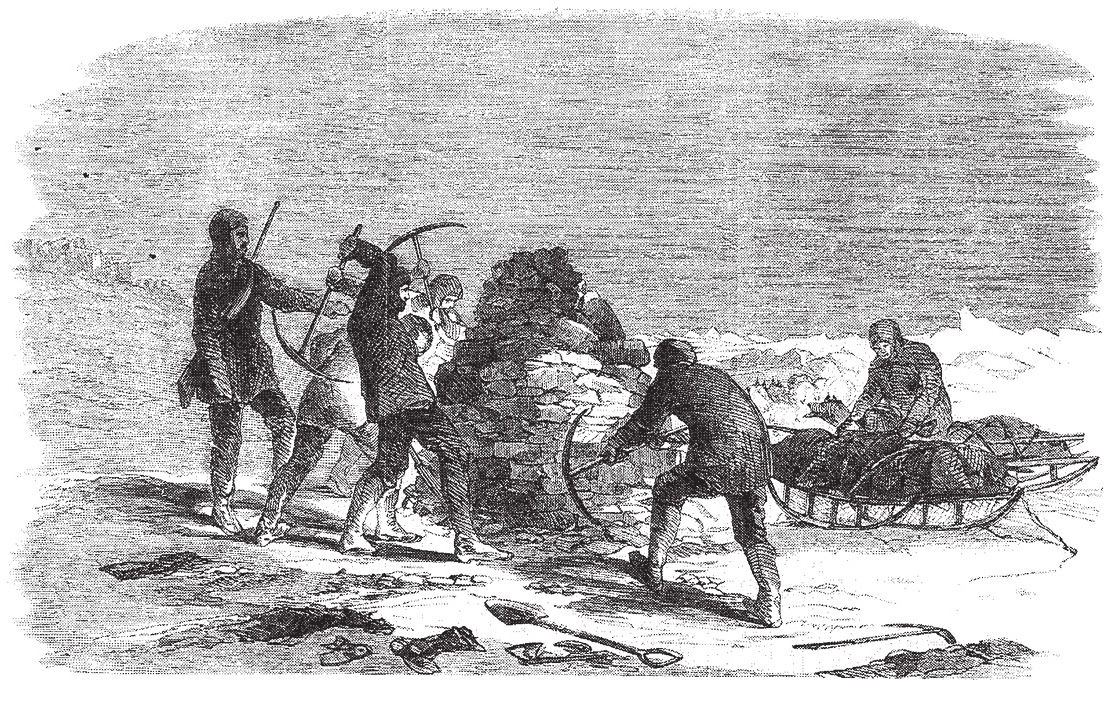

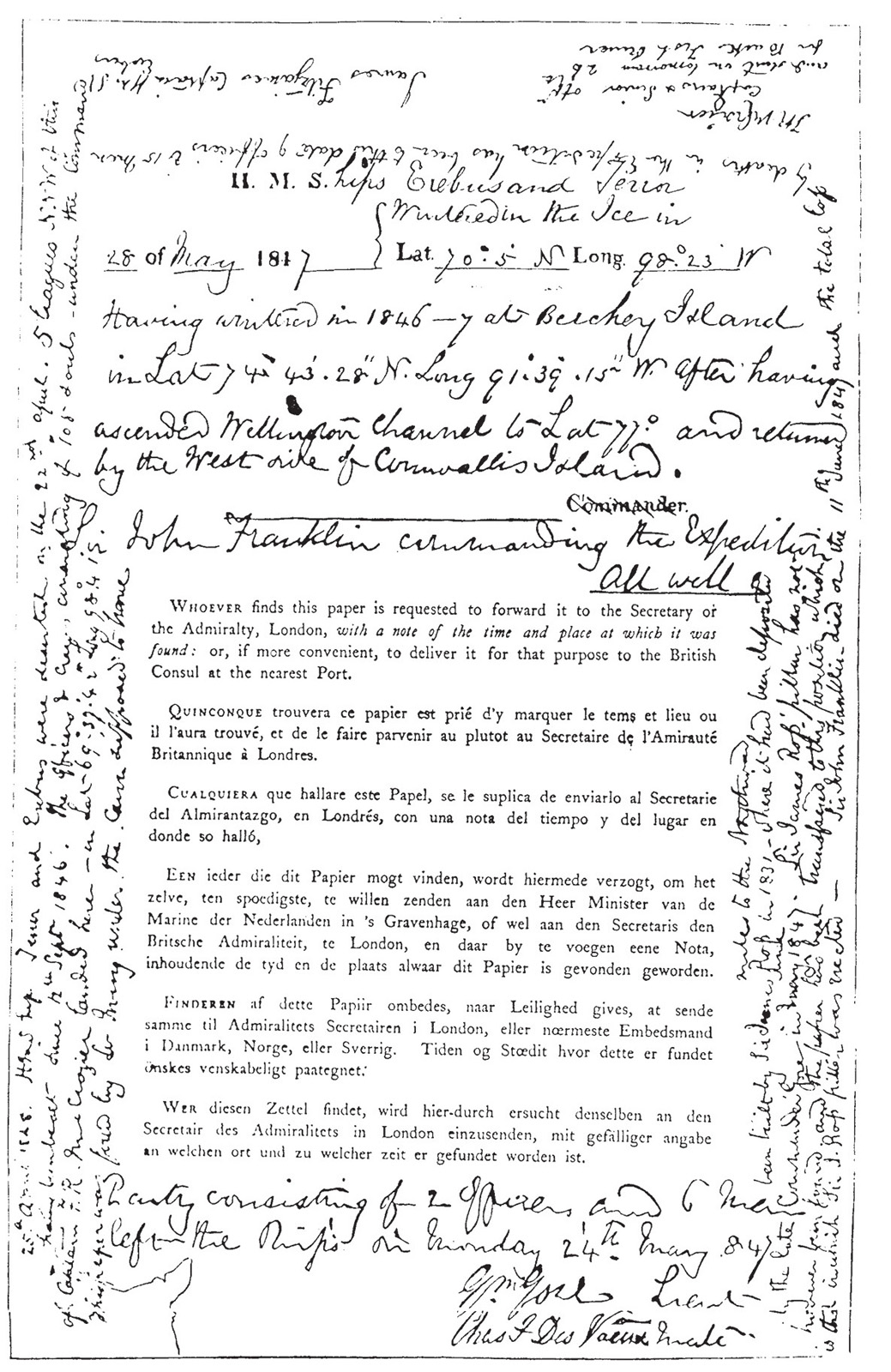

âa possibility raised because of another discovery. The most important artefact of the Franklin searches had been located three weeks before the skeleton was found, as Hobson surveyed the northwest coast of the island. On 5 May, the only written record of the Franklin expeditionâchronicling some of the events after the desertion of the ships and consisting of two brief notes scrawled on a single piece of naval record paperâwas found in a cairn near Victory Point. The ï¬rst, signed by Lieutenant Graham Gore, outlined the progress of the expedition to May 1847:

28 of May 1847. HM Ships Erebus and Terror⦠Wintered in the Ice in Lat. 70Ë 05â² N. Long. 98Ë 23â² W. Having wintered in 1846â7 at Beechey Island in Lat. 74Ë 43â² 28â³ N Long. 90Ë 39â² 15â³ W after having ascended Wellington Channel to Lat. 77Ëâand returned by the west side of Cornwallis Island. Sir John Franklin commanding the Expedition. All well. Party consisting of 2 officers and 6 Men left the Ships on Monday 24th. May 1847. Gm. Gore, Lieut. Chas. F. Des Voeux, mate.

Lieutenant Hobson and his men opening the cairnâ near Victory Point, King William Islandâthat contained the only written record of the Franklin expedition's fate.

The document is notable for an inexplicable error in a dateâthe expedition had wintered at Beechey Island in 1845â46, not 1846â47âand its unequivocal proclamation: “All well.” Originally deposited in a metal canister under a stone cairn, the note was retrieved eleven months later and additional text then scribbled around its margins. It was this note that in its simplicity told of the disastrous conclusion to 129 lives:

(25th April) 1848âHM's Ships Terror and Erebus were deserted on the 22nd April, 5 leagues NNW of this, having been beset since 12th Septr. 1846. The Officers and Crews, consisting of 105 souls, under the command of Captain F.R.M. Crozier landed hereâin Lat. 69Ë 37â² 42â³ Long. 98Ë 41â². This paper was found by Lt. Irving under the cairn supposed to have been built by Sir James Ross in 1831, 4 miles to the Northward, where it had been deposited by the late Commander Gore in June 1847. Sir James Ross' pillar has not however been found, and the paper has been transferred to this position which is that in which Sir J Ross' pillar was erectedâSir John Franklin died on 11th of June 1847 and the total loss by deaths in the Expedition has been to this date 9 Officers and 15 Men.

James Fitzjames, Captain HMS Erebus.

F.R.M. Crozier Captain and Senior Offr.

and start on tomorrow 26th for Backs Fish River.

The notes found in the cairn at Victory Point on 5 May 1859, by Lieutenant Hobson and his men.

“So sad a tale was never told in fewer words,” M'Clintock commented after examining the note. Indeed, everything had changed in the eleven months between the two messages. Beset by pack-ice since September 1846, Franklin's two ships ought to have been freed during the brief summer of 1847, allowing them to continue their push to the western exit of the passage at Bering Strait. Instead, they remained frozen fast and had been forced to spend a second winter off King William Island. For the Franklin expedition, this was the death warrant. There had already been an astonishing mortality rate, especially among officers. Deserting their ships on 22 April 1848, the 105 surviving officers and men set up camp on the northwest coast of King William Island, preparing for a trek south to the mouth of the Back River, then an arduous ascent to a distant Hudson's Bay Company post, Fort Resolution, which lay some 1,250 miles (2,210 km) away. M'Clintock described the scene where the note had been discovered:

Around the cairn a vast quantity of clothing and stores of all sorts lay strewed about, as if at this spot every article was thrown away which could possibly be dispensed withâsuch as pickaxes, shovels, boats, cooking stoves, ironwork, rope, blocks, canvas, instruments, oars and medicine-chest.

Why some of these items had been carried even as far as Victory Point is another of the questions that cannot be answered, but M'Clintock was sure of one thing: “our doomed and scurvy-stricken countrymen calmly prepared themselves to struggle manfully for life.” The magnitude of the endeavour facing the crews must have been overwhelming, and the knowledge of its futility spiritually crushing. It also ran contrary to the best guesses of other leading Arctic explorers. George Back, who had explored the river named for him in 1834, was certain Franklin's men would not have attempted an escape over the mainland: “I can say from experience that no toilworn and exhausted party could have the least chance of existence by going there.” John Rae thought that “Sir John Franklin would have followed the route taken by Sir John Ross in escaping from Regent Inlet.”

To this day, the route of the expedition retreat confounds some historians, who, like Rae, believe a much more logical and attainable goal would have been to march north and east to Somerset Island and Fury Beachâthe route by which John Ross had made good an escape from an ice-bound ship in 1833. Fury Beach was not much further for the crews of the

Erebus

and the

Terror

than it had been for John Ross's crew of the abandoned

Victory.

It was also the most obvious place for a relief expedition to be sent, and James Clark Ross did indeed reach the area with two ships, ï¬ve months after the

Erebus

and

Terror

were deserted.

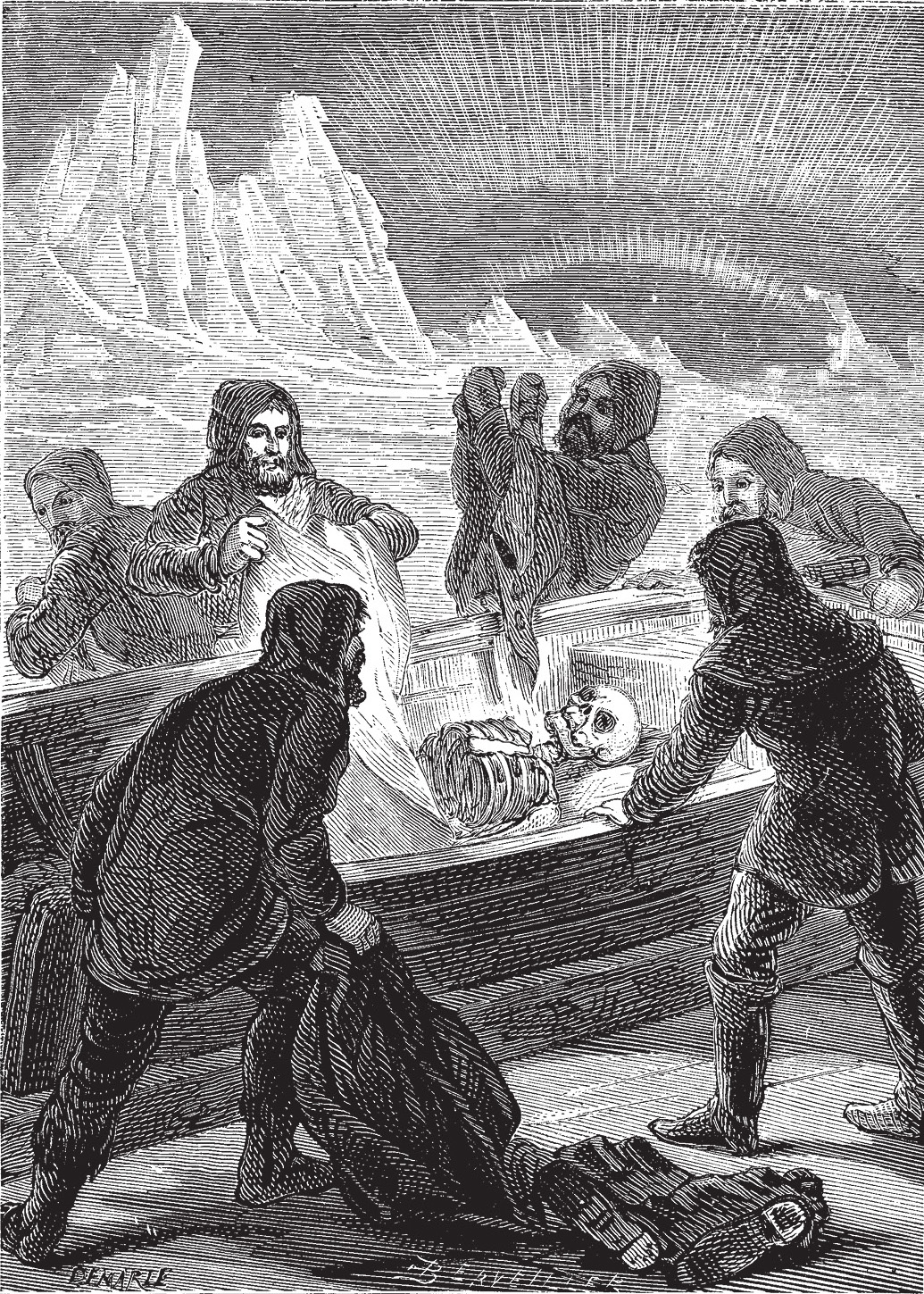

Instead, after quitting their camp on 26 April, the crews moved south along the coastline of King William Island, man-hauling heavily laden lifeboats that had been removed from the ships and mounted on large sledges. Plagued by their rapidly deteriorating health, the crews were then overcome by the physical demands of the task. M'Clintock found what appeared to have been a ï¬eld hospital established by Franklin's retreating crews only eighty miles into their trek. He suspected scurvy. Speculation also focussed on the tinned food supply. Inuit later told of some of their people eating the contents of the tins “and it had made them very ill: indeed some had actually died.” As for Franklin's men, many died along the west and south coasts of King William Island.

Later, Hobson found a vivid indication of the tragedy when he located a lifeboat from the Franklin expedition containing skeletons and relics. Men from Franklin's crews had at last been found, but the help had come a decade too late. When M'Clintock later visited the “boat place,” he described his tiny party as being “transï¬xed with awe” at the sight of the two human skeletons that lay inside the boat. One skeleton, found in the bow, had been partly destroyed by “large and powerful animals, probably wolves,” M'Clintock guessed. But the other skeleton remained untouched, “enveloped with cloths and furs,” feet tucked into warm boots to protect against the harsh Arctic cold. Nearby were two loaded double-barrelled guns, as if ready to fend off an attack that never came.

M'Clintock named the area, on the western extreme of King William Island, Cape Crozier. The boat, which had been carefully equipped for the ascent of the Back River, was 28 feet (8.5 metres) long; M'Clintock estimated the combined weight of the boat and the oak sledge it was mounted on at 1,400 pounds (635 kg).

M'Clintock discovers a lifeboatâcontaining skeletonsâ from the Franklin expedition.

Careful lists of the “amazing” quantity of goods also contained in the boat were compiled. Everything from boots and silk handkerchiefs to curtain rods, silverware, scented soap, sponges, slippers, toothbrushes and hair-combs were found. Six books, including a Bible in which most of the verses were underlined,

A Manual of Private Devotions

and

The Vicar of Wakeï¬eld,

were also discovered and scoured for messages, but none were found. The only provisions in the boat were tea and chocolate. M'Clintock judged the astonishing variety of articles “a mere accumulation of dead weight, of little use, and very likely to break down the strength of the sledge-crews.” Perhaps strangest of all was the direction in which the boat was pointing, for instead of heading towards the river that was the target of the struggling survivors, the boat was pointed back towards the deserted ships. M'Clintock guessed that the party had broken off from the main body of men under the command of Crozier, and was making a failed attempt to return to the ships for food: “Whether it was the intention of this boat party to await the result of another season in the ships, or to follow the track of the main body to the Great Fish [Back] River, is now a matter of conjecture.”