Full Moon (27 page)

“Why don’t blackmailed people come to the police?” Blair wondered. “What a

damned fool!”

“Was he? I don’t think he cared for the blackmail at all. He made no

bargain with Wu Tu; He knew she would not dare to accuse him, because it was

she and her agents who had looted the gold. What he decided to do was to come

back and look for the servant, even if he had to follow him into the fourth

dimension.”

“Did he think he could bring him back?”

“He didn’t know.”

“And you agreed?”

“I wasn’t asked. He went and did it. What would have been the use of my

telling you, for instance, what I thought had happened? Would you have

believed me? You believe me now. But would you have believed me then?”

“If you weren’t consulted, how do you know what he did?”

“I will show you presently. But I should have been very stupid not to

guess what, he had done. He left a note for me saying where he was going, and

reminding me that he had already conveyed his property to me by deed of

trust. He asked me to burn the note and say nothing. L did. We had often

talked over what it might mean to step off into the fourth dimension, and

perhaps meet each other there.

“Neither of us ever had the least doubt of a life after death. But we

agreed in not liking the prospect of death, it’s such a messy and sometimes

such a cruel business. I like life. I love it. But the thought of life in

love with you. and you indifferent, was such a drab, unlovely prospect that I

made up my mind to follow father if I could get into the caverns. I had been

unable to get in lately. So when Chetusingh brought me a message, that I

thought couldn’t possibly be from you, I pretended to believe, and I came

like a shot,”

“Like a shot!” said a whispering echo.

“Wu Tu wants to follow him?”

“I think she wants to look into the fourth dimension. Wu Tu craves power.

She believes she can learn black magic. She believes in it, and I believe

she’s afraid of it.”

“Yes, she does, and she is.” said Blair. “Well, she’s afraid of prison.

She’s afraid of death. She’ll learn all about both, if we ever gel out of

here alive. She’ll have to swing tor killing Zaman Ali—not. that he

didn’t deserve it. I feel sorry for her. But when a woman like Wu Tu slips

up, she has too many debtors and rivals and other sorts of deadly enemies to

have a chance to escape the gallows. I know many a worse blackguard than Wu

Tu who won’t get hanged, but who will laugh with relief when it happens to

her.”

“You’re not vindictive?”

“No. Vindictive people are all contemptible, and most of them are

self-righteous swine. Wu Tu is about the opposite of my idea of a desirable,

but if I could. I’d save her for the sake of what she has taught me, about

crooks and half a hundred other things.”.

“Look!” said Henrietta.

The rind of the moon rose golden in the gap, and the Pleiades vanished.

The entire cavern became filled with dim light: but the great cone glittered

in the midst as if cold fire burned within. The woman remained invisible, but

there were swirling shapes, like opal clouds, inside the cone. They changed

each second, with each fractional change of the moon’s height.

“Wait!” said Henrietta.

“Wait! Wait!” echoes whispered.

They stood up, hand in hand. Second by second the cone grew brighter,

until its summit glowed like molten silver—changing—

changing—the glow descending. Slowly, as the full moon stole upward

past the brim of the gap, the entire cone grew suddenly silver—and then

suddenly transparent. The silver vanished. It gleamed pure crystal. The

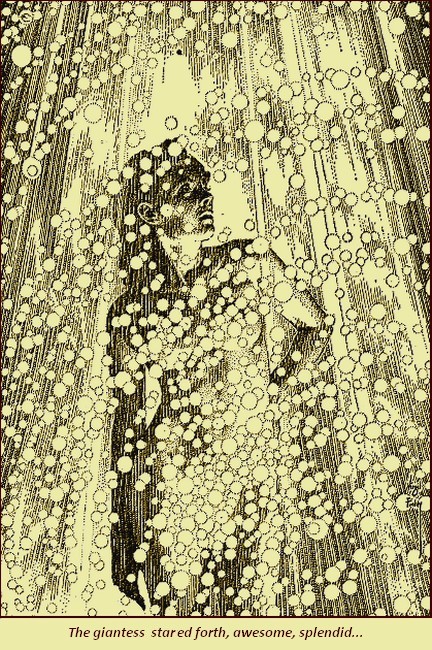

giantess stared forth like a splendid statue, dead and yet strangely

lifelike.

“Come,” said Henrietta.

“Come!” an echo whispered in Blair’s ear. But he stared and stood still.

It was nearly a minute before he yielded to the tug of Henrietta’s hand and

followed her. Even the echoes of their footsteps were like sounds in a

dream.

There was no longer need for the electric torch. Moonlight filled the

cavern: the cone diffused it, conquering all shadows except in the segment

behind the mound: even there it was not totally dark. Henrietta led into the

shadow until the cone stood straight between them and the moon, and they

could see the Woman, weirdly radiant. She looked alive, in motion, walking

forward; tired eyes refused to believe she was not moving. From beneath, at

that angle, she seemed to be staring upward at the ledge that surrounded the

pit.

At the rear of the mound, illuminated dimly by the all-pervading glow, a

flight of wide stone steps ascended fifty or sixty feet to a narrow

egg-shaped opening. Steps and opening were probably invisible from the ledge:

they curved on the face of the mound and were flanked by a natural balustrade

of cream-hued stalagmite, worn soap-smooth where ancient hands, ascending and

descending, had pressed on its upper surface. They were irregular steps: no

two were alike: several of them were three feet higher than the step below.

It was a stairway for a giant, worn on the surface by ages of use.

They ascended together, laboring up hand-in-hand, until they stood

exhausted before the egg-shaped opening. Its small end was downward, and

around its edge were vaguely snake-like tracings on the stone. Within was

darkness. Blair switched on the torch. They ascended a smooth-walled passage,

ten feet high, four feet wide, that spiraled gradually upward, worn along its

midst into a shallow trough by feet that must always have marched in Indian

file.

They could hardly hear themselves speak, hardly hear their own footfall;

the sounds they made seemed to travel along in front of them, so that the

sensation was of following other people into the home of all the booming

noises in the world.

It was a long climb; the passage apparently made two complete ascending

spirals within the mound. But at last there began to be light —so much

light that the torch was no longer needed. They came to another egg-shaped

opening in a weirdly carved wall. Through that the light shone from an

enormous chamber that except for two thirds of the floor contained not one

flat surface. Its curved walls seemed to be built of frozen moonlight. There

was nothing else to which to compare it.

“It is only like this in full moonlight,” Henrietta whispered. “When the

sun shines nothing can live in this place.” Even a whisper sighed like wind

until its echo flowed back past them and down the tunnel.

In the midst of the place, arranged in an elongated oval, there were

eighteen crystalline, apparently unhewn, natural columns. They supported the

roof and surrounded an oval hollow that suggested a pool, but there was no

water in it. Its floor looked like molten metal in the light that streamed

through the roof, between the columns. The mirror-like surface of the pool

caught, suffused and spread the light outward between the columns toward the

concave surface of the chamber wall, which reflected it back, confused but

soft and tolerable. The shadowy reflections of the columns seemed to swim

within the wall, in fantastic and innumerable curves that changed their shape

as the observer moved.

Sensation reeled. The slowly moving moonlight pouring through the gap on

the summit of Gaglajung touched millions of microscopic prisms in the cone

that contained the Woman. The light came through the cone into the chamber,

magnified and broken into soundless, formless, spastic symphonies of chaos.

The place swam in motion. Even the columns seemed to move, in an

incomprehensible, measureless dance, like reeds in a whirlwind. But the air

was stifling; there seemed to be no draught whatever, and that increased the

weirdness.

Up between and above the columns, seen through stone as clear as crystal,

like an undead corpse in water moved by multitudes of currents, stood the

Woman of Gaglajung: By some freak in the shape of the crystalline stone, she

appeared now to be staring downward at her own reflection. It felt like

looking up through deep, clear water at an unearthly bather—monstrous,

meditative, silent. When they stood still and made no echoes, there was such

silence that Blair’s straining ears heard his own and Henrietta’s

heartbeats.

Moment after moment the light increased. The oval hole through which they

had entered was not at the chamber’s wider end but about fifteen feet to one

side of it. At the narrower, far end of the chamber, on the floor, against

the wall, confusingly reflected amid tangled images of columns on the wall’s

curved surface, there was something not quite recognizable and yet familiar

that caught Blair’s eye. He walked toward it, treading as quietly as he could

because his footsteps filled the place with noise as weirdly broken and

confusing as the light.

Henrietta shook off her sandals and followed, but even bare feet stirred a

whispering, like wind amid reeds. They passed between the columns, skirting

the curved surface of the egg-shaped pool. It had been swept; the dust of

ages lay in a heap between two columns, except for a small oval space in the

center.

Seen close, that looked like polished, aluminum. But the part in the

center, about six or seven feet long, defied imagination. It appeared to be

neither solid nor liquid. It looked like a pool of pure moonlight. It was

very difficult to look at steadily, ‘but reflected within it, reversed,

reduced in size and gazing upward, was the Woman. There was nothing else

reflected in that central portion. Blair made a move to examine it more

closely.

“Don’t!” Henrietta exclaimed—instant—sudden— clutching

his arm. Her exclamation filled the place with rolling thunder. Blair saw the

fear in her eyes. He sensed no danger, but saw that she did, so he took her

hand and continued his way to the wall at the far end. The light, continually

more confusing, changed every second. They were close to the

wall—within six strides of it—before he saw that the curious

object was some clothing.

It was a coat, folded with military neatness, topped by a two-decker Terai

hat of thin gray felt, such as Frensham always wore,when not in uniform.

Slightly protruding from the jacket pocket was a flat metal first-aid

kit-box. Beside the hat there was an empty cigarette case of thin, polished

wood, a box of matches and a felt-covered water-bottle with a fitted metal

cup. Beside those was a bit of black candle-wick amid the shapeless residue

of a burned-out candle. Three dead matches and three closely burned cigarette

ends lay in a neat little heap together, near the wall.

“He must have sat here smoking, waiting for the moon,” Henrietta

whispered. “It was at full moon that the deaf-and-dumb man vanished.”

“Vanished—vanished!—” said the echo and went whispering down

the tunnel—“Vanished —vanished!—”

Blair searched the jacket. There was nothing in the pockets. He stared at

Henrietta—refolded the jacket:

“Why the devil did he take his clothes off?”

“The deaf-and-dumb man did,” she answered. “And he found it—the

fourth dimension. He disappeared.”

“Disappeared—disappeared—” said the echo. Blair glanced

upward, but from that end of the chamber the giantess was invisible.

Henrietta whispered again:

“Father made experiments, remember.”

She moved the coat and the other things, signed to him, and they sat where

it had been, side by side, with their backs to the wall, heads touching,

clasped in each other’s arms. A line drawn then between them would “have

passed exactly down the center of the place between the columns and across

the pool, to the middle of the broad end of the chamber. The oval opening by

which they came in was on their left-front, hidden from them by the

columns.

The light kept growing stronger every second, and yet curiously soft:

there was no perceptible strain on the eyes, although there was a feeling of

confusion. Attention wandered. It was like staring in a dream at fascinating

and convincing unreality. There appeared an exceedingly thin line, like a

plane of light seen edgewise between the pool and the roof—almost like

one filament of the Aurora Borealis. When Blair moved his head it

vanished.

When he resumed his position it reappeared. It refused to be placed. It

was there and not there, but it seemed to pass upward, through the

transparent roof toward the Woman. It shone, but it was less like a ray of

light than like one of those slanting rays that Cubists paint, to lead

imagination toward new frontiers of realism. It moved, but there was no

describing its movements: its soundlessness suggested sound turned inside

out, rather than silence.

Henrietta whispered excitedly: “Do what he did!”

Abruptly, she slipped off her clothes. Even so. Blair hesitated.

Convention dies harder in a man. But Henrietta seemed perfectly

unself-conscious. Chin on knees, she stared straight at the dreamlike line

between the columns, not turning her head when she spoke again,

low-voiced:

“I don’t know why—perhaps nobody can know why—this only

happens in full moonlight. You can’t see unless you’re naked. Why, I don’t

know. But you’ll have to resist. You must hang on.”