Gallipoli

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

At dawn on 25 April 1915, Allied forces landed on the Gallipoli Peninsula in present-day Turkey, with the hope of securing the Dardanelles and thus allowing the Imperial Fleet to go all the way to Constantinople. If all went well, it was Winston Churchill and Lord Kitchener's impassioned view that the Ottoman Empire would be knocked out of the war.

Â

It did not quite go as they planned. Of course, the story has been told before, but in this book FitzSimons, with his trademark vibrancy and expert melding of writing and research, not only recreates the disaster as experienced by those who endured it or perished in the attempt, he takes us everywhere: from the secret deliberations of the British War Council, to the Ottoman leadership, to the trenches on both sides of no-man's-land. True as ever to his mantra of âMake it live and breathe!', FitzSimons conveys us to the centre of the story each step of the way; and is able to shine new light on the whole campaign, in this its Centenary year.

To Charles E. W. Bean, Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett and Keith Murdoch. The first for so skilfully and courageously chronicling many of the events herein; the latter two for their bravery in influencing the course of events.

I dips me lid.

Remote though the conflict was, so completely did it absorb the people's energies, so completely concentrate and unify their effort, that it is possible for those who lived among the events to say that in those days Australia became fully conscious of itself as a nation.

Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914â1918, Vol. I

History will undoubtedly concede that strategically the attack on Constantinople is absolutely sound, and the results of success will be far-reaching. It is the manner in which it is being carried out, which is causing all the trouble.

Ellis Ashmead-Bartlett, The Uncensored Dardanelles

I could pour into your ears so much truth about the grandeur of our Australian army, and the wonderful affection of these young soldiers for each other and their homeland, that your Australianism would become a more powerful sentiment than before. It is stirring to see them, magnificent manhood, swinging their fine limbs as they walk about Anzac. They have the noble faces of men who have endured. Oh, if you could picture Anzac as I have seen it, you would find that to be an Australian is the greatest privilege the world has to offer.

Keith Murdoch to Andrew Fisher (âThe Gallipoli Letter'), 23 September 1915

The Black Sea, the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles

Location of Rabaul in relation to Australia

Cairo district army camps and hospitals

Lemnos, Imbros, Tenedos and the Dardanelles

Gallipoli Peninsula in relation to the Dardanelles

Naval attack on the Dardanelles, 18 March 1915

Intended objectives and actual position for Anzacs, 25 April 1915

Map of First, Second and Third Ridge

Troop positions, 25 April 1915

Quinn's PostâCourtney's Post trench system

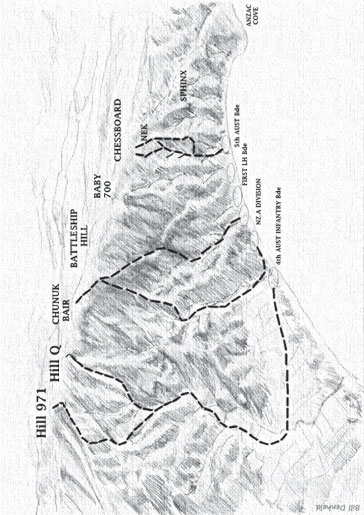

Opposing trench lines, 6â10 August 1915

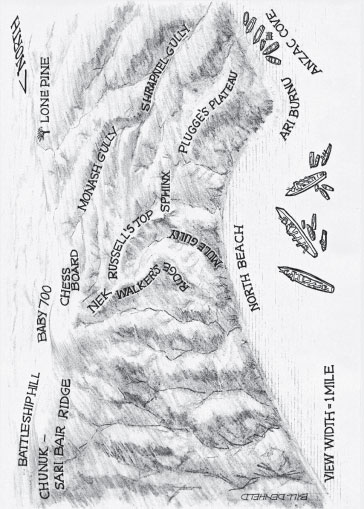

Sari Bair Range from the shore

Allied and Turkish trench dispositions, Hill 60, 26 August 1915

Allied and Turkish trench dispositions, Hill 60, pre-attack, 27 August 1915

Anzac Cove and Lone Pine, by Bill Denheld

View over Gallipoli Peninsula, by Bill Denheld

Gallipoli attack lines, by Bill Denheld

Gallipoli and I go back a long way.

As the youngest of seven kids, born to parents who had returned from serving in the Second World War to carve out a farm in the bush at Peats Ridge â just an hour north of Sydney â the very name âGallipoli' resonated for me like no other. A place of extraordinary deeds, of inspiring courage and sacrifice, it made you proud to be an Australian. Knowledge of it went with

being

an Australian. I learned about it at primary school; I heard about it every Anzac Day service up at Central Mangrove RSL; and I frequently thought about it,

at the going down of the sun, and in the morning

â¦

Sure, I was sort of proud of Mum and Dad and their service in the Second World War â Mum as an army physiotherapist, helping rehabilitate the veterans of Milne Bay and Kokoda; and Dad at El Alamein and in New Guinea â but it wasn't as if they had been at Gallipoli, where I knew the

real

action had taken place.

I studied it quite seriously at high school, I read about it on my holidays and wrote an essay on it while at the University of Sydney. My reverence for it blossomed to the point that, as a rugby player living and playing in Italy in the mid-1980s, on my '84/'85 Christmas break, I drove my tiny little Fiat all the way through the Iron Curtain, through Yugoslavia and Bulgaria to first Istanbul, and then of course down to Gallipoli.

Alone â long before visiting these battlefields had become something of a rite of passage for many young Australians â I wandered around, awe-struck at the savagery of the terrain, how the cliffs rose all but straight from the shore, how the trace of the trenches meandered in parallel lines so close together, how some of the gullies they'd fought in and for looked rather more like abysses to my eyes.

Standing on the beach below the spot known as The Sphinx, I noticed a great deal of erosion in the landscape all around, and wondered about it until I suddenly realised. That was not mere erosion, it was the scars of thousands of artillery shells hitting those hills!

At Lone Pine Cemetery, amid all the gravestones marked with such words as

DUTY NOBLY DONE, HE DIED IN A FAR COUNTRY/FIGHTING FOR/HIS NATIVE LAND, A MOTHER'S THOUGHTS OFTEN WANDER TO THIS SAD AND LONELY GRAVE

⦠I noted an epitaph that quite shocked me, going something like

DIED IN A FOREIGN FIELD. AND FOR WHAT?

Coming back from the battlefield towards the nearest town â Gallipoli itself â I gave three hitchhiking Turkish workers in blue overalls a lift up to the next town, and though the language barrier between us was insurmountable, I was a tad amazed that they seemed extremely friendly, even after I identified myself as â steady, fellas,

steady

â an

Australian.

Would I be so hail-fellow-well-met with someone from a nation that had come to my shores and killed 90,000 of my countrymen?

No.

I returned home to Australia, proud that I had made my pilgrimage to sacred soil, and then embarked on a journalistic career, covering many subjects but always with an eye out for Anzac Day stories. I was particularly stunned by the reaction I received to a yarn I wrote about a cricket match played on the shores of Gallipoli, even while Turkish shells were bursting all around. Letters, phone calls, people stopping me in the street, expressing their wonder at the Diggers' bravery â¦

Many years on, stories of Gallipoli were still striking so many chords with the Australian people you could play an anthem to it. In the late 1990s, for no reason I can think of, I suddenly started taking my kids to Anzac Day services in town.

In April 1999, I was in my car heading down Sydney's Market Street, about to turn left onto Sussex Street, to the

Sydney Morning Herald

building, when some highbrow historian on ABC Radio used the phrase âwhen the Australians invaded Turkey, at Gallipoli'.

Invaded?

Such an ugly, aggressive, non-reverential word! Yes, I suppose, technically, Gallipoli was on Turkish soil â even though it was GALLIPOLI â and, strictly speaking, if you wanted to really get pernickety about it, our blokes didn't really have the Turkish blessing to land on their shores. So, if your measure was hoity-toity historical, then it just possibly could be construed as an âinvasion', so long as you put some monster quotation marks around it. But it sat very uncomfortably with me, and was the first time I had been obliged to think of the whole idea of the landing on Gallipoli shores in less than holy terms. But the more I thought about it as the years passed, the more I drifted into a rather more sober view.

To open my 2004 book on Kokoda, I quoted the words of Paul Keating, shortly after, as Prime Minister, he famously kissed the hallowed ground in New Guinea in 1992: â

The Australians who served in Papua New Guinea fought and died, not for defence of the old, but the new world. Their world. They died in defence of Australia and the civilisation and values which had grown up there. That is why it might be said that, for Australians, the battles in Papua New Guinea were the most important ever fought

.'

1

Now

that

resonated.

âAfter all,' I would occasionally note in after-dinner speeches, when feeling brave, âat Gallipoli, they fought for England and lost. At Kokoda, they fought for Australia and won.'

Other times, I would note, âHow weird we Australians are! After the Germans invaded Poland in 1939, they moved their way through most of the rest of Europe, knocking over army after army, and got all the way to North Africa, still without registering a defeat. The

first time

the Germans were stopped was when they came up against the Australians at Tobruk. Same with the Japanese! After dropping bombs on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese Imperial Army knocked over the Philippines, moved down through the Malayan Peninsula and knocked over Singapore, before landing in New Guinea ⦠where they were defeated, for the first time, by the Australians at Milne Bay and then Kokoda. So we have on our national military record that our soldiers were the first to stop the Germans and the Japanese during the Second World War. But when it comes time for a day of military remembrance, we say, “Yes, yes, yes, that was us that stopped the hitherto unstoppable Germans and Japanese, but did we ever tell you about the time we got sent packing by the Turks?”'

There is usually a momentary stunned silence â someone said something

against

reverence for Gallipoli? â before people give rueful smiles and acknowledge it

is

a strange thing.

Broadly, after immersing myself in writing about the Second World War, I came to the view that the whole Gallipoli story was overdone, and that Australia's emotional centre of gravity when it came to our military history had moved forward.

Still, as the Centenary of Gallipoli approached, I found myself on both the Council of the Australian War Memorial and the Anzac Centenary Advisory Board, two institutions where I was exposed to many fascinating angles to Gallipoli I had not previously considered. Again I was given cause to reflect on just what it was all about, what it all meant from the perspective of 100 years on.

I particularly remember a presentation to the Anzac Centenary Advisory Board in early 2013 made by a very learned academic from Monash University, Professor Bruce Scates, where, at our behest, he presented 20 stories about Australians who had fought in the First World War and what had happened to them, including most particularly Hugo Throssell, as part of a broad plan to present 100 such stories to the public. Each story seemed more horrifying than the last, in detailing the appalling consequences of young men dying grisly deaths and leaving behind ruined families.

At the end of his presentation, no one spoke for a good 20 seconds.

Devastating!

âDid ⦠uh ⦠um, anything

good

happen to anyone?' one of the people around the table asked.

His expression said it all: NO.

âSurely the bad outweighs the good in war,' the good Professor finally replied firmly. âWe can't afford to lose sight of that.'

When someone suggested that the most disturbing cases be cut from the presentations and be replaced with âpositive, nation-building stories', he bristled.

âWe owe the

truth

to a generation that suffered so much,' he said. âAnd the truth is the effect on most lives was devastating. If you try to make me put a positive spin on it, I shall resign.'

In March 2013, once I'd embarked on a book about it, I revisited Gallipoli and again walked through Lone Pine Cemetery, intent on finding that inscription that had haunted me from 30 years earlier â

DIED IN A FOREIGN FIELD. AND FOR WHAT?

Alas, among the 1167 graves there, I couldn't find it, but I did come across other moving epitaphs, such as that for Private L. J. Dawson, of the 1st Battalion,

OH FOR THE TOUCH OF A VANISHED HAND,

which I quoted in my newspaper column upon my return. It prompted a flurry of correspondence, where readers sent in other epitaphs they had seen at Gallipoli, including one for Trooper Eric Chalcroft Bell, Killed In Action on 19 May 1915, aged 22:

LOVING HUSBAND OF NELLIE, BELOVED FATHER OF EVA, DULCIE & ERICA

.

What, I wondered in my column, became of Nellie, Eva, Dulcie and Erica? The answer, coming from a reader descended from them, was devastating, involving grinding poverty, orphanages and sexual abuse of those daughters.

It influenced the way I wrote this book. I did not want to go down the âThey died for our freedom' path, because however noble the intent of many of them, I have never come across the âpursuit of freedom' or its like as a motivating factor in any of the myriad letters or diaries I've read, and though âfighting for Australia' and âdoing my duty' was indeed a frequent refrain, in many cases the bitter truth, as noted by Charles Bean, is they just

died.

Tragically. Too often for not even the gain of one yard of land. Did they even have right on their side?

I happened to be at the Australian War Memorial in 2013 when Paul Keating, commemorating the 20th anniversary of the reinterment of the Unknown Soldier, said, âThe First World War was a war devoid of any virtue. It arose from the quagmire of European tribalism. A complex interplay of nation-state destinies overlaid by notions of cultural superiority peppered with racism â¦'

2

The more I researched, the more I began to wonder whether it was a fairer summation to say that many were in fact sacrificed on the altar of British Imperialism?

I began the book with these things in mind, though â as with my last book, on Ned Kelly â I didn't want to draw specific conclusions. I wanted to detail

what happened

across the board, not just from ground level with the Australian soldier, but also for the New Zealanders, the Turks, the Brits and other nationalities, the officers and all of the politicians and leaders who put them all there in the first place.

As with all of my books with historical themes, I wanted to make it read like a novel, but fill it with accurate raw detail and perch it on 2000 or so firm footnotes to show that it is nevertheless real. For the sake of the storytelling, I have occasionally created a direct quote from reported speech in a newspaper, diary or letter, just as I have changed pronouns and tenses to put that reported speech in the present tense. I have equally occasionally restored swearing words that were blanked out in the original newspaper account due to the sensitivities of the time. Always, my goal has been to determine the most likely words used, based on the documentary evidence presented.

Trying to bring the Turkish side of the saga to life became problematic in the storytelling when the Turks and Australians used different geographical nomenclature to describe the same landform. To get around this, I have broadly followed Charles Bean, with the most notable exception being â

dere

' â a Turkish word meaning âgully'. No doubt, for example, âSazli Dere' is the name used by the Turks, but the narrative is clearer as âSazli Gully', and only rarely did the Diggers and officers themselves use Turkish terms for landforms.

For the same reason of remaining faithful to the language of the day, I have stayed with the imperial form of measurement and used the contemporary spelling. Though the Turks used âIstanbul' to describe their ancient capital, for ease of narrative told from a fundamentally Anglo perspective I have used âConstantinople'.

One happy circumstance in doing this book was that the three principal members of the research team I have worked with on so many previous books happened to have particular strengths on this subject.

Libby Effeney lived in Turkey for five years, speaks the language and has strong contacts within the Turkish historical academic community. She was able to visit Turkey on my behalf, finding the nuggets of gold to bring the Turkish side of things to life. A PhD student from Deakin University, her intellect, work ethic, creative nous and drive to get to the bottom of things was invaluable in all facets of this book, and I warmly thank her for all her work, including liaising with the other researchers on specific subjects. She was a joy to work with throughout, combining great professionalism by day with warmth in emails at midnight, assuring me it would all come together in the end. When she becomes a Professor, I will boast of having worked with her. I already do.

Sonja Goernitz is a dual GermanâAustralian citizen familiar with the highways and byways of German historical institutions, and she was able to return to her homeland to winkle out gems from the German side of the equation. She, too, was tireless in her efforts, and I thank her.

My friend of 35 years standing, Henry Barrkman, was living in Dublin for most of the course of writing the book and was able to access the London Archives relatively easily. An angel of accuracy, a demon for detail, his impact on this manuscript was immense. I thank him most particularly for two things: always challenging the accepted version of events until such times as original documentation proved it; and trawling the minutes of the hours of the

days

of endless meetings of the War Council 100 years ago in London, noting who said what to whom and when, to work out how the actual decision to go to Gallipoli was made. All up, a bravura performance.