Gallipoli (8 page)

Authors: Peter FitzSimons

8 AUGUST 1914, KITCHENER'S MOB MASSES

And now the posters begin to appear all over London hoardings, calling for volunteers for the âNew Army'. They are soon to be referred to as âKitchener's Mob', for the facts that the face soon appearing on those posters is that of Lord Kitchener and the men enrolled really are seen by the regulars as an inexperienced, unprofessional mob.

As to those regulars, they have already been formed into a British Expeditionary Force, which on this very day gets its mobilisation orders to depart for France on the morrow. In the words of one of the Highlander troops, their job will be to âgie a wee bit stiffening to the French troops'.

54

Most are desperately hoping to be given a chance to kill Germans.

EARLY EVENING, 10 AUGUST 1914, CONSTANTINOPLE, A SON HAS BEEN BORN TO US

Another night. Another meeting. This is between Colonel Hans Kannengiesser of the German Military Mission and the Ottoman Minister of War, Enver. Suddenly, there is something of a commotion outside. Someone wishes to interrupt their conversation?

âLord Kitchener Wants You' recruitment poster, 1914 (AWM ARTV0485)

It proves to be the very pushy German nobleman officer Lieutenant-Colonel Friedrich Freiherr Kress von Kressenstein, who has news that cannot wait, and which â he bristles with righteous authority and glares through his rimless glasses â needs an urgent decision. âFort Ãanakkale,' Kressenstein says, âstates that the German warships

Goeben

and

Breslau

are lying at the entrance to the Dardanelles and request permission to enter. The fortress asks for immediate instructions to be sent as to the procedure for the commanders of the Kum Kale and Sedd-el-Bahr.'

55

Enver prevaricates, which is unlike him. He knows he requested

Goeben

, but that was days ago now. Indeed, the Ottoman Military Attaché in Berlin had informed him as early as 3 August that he had been told âvery confidentially' that Kaiser Wilhelm II might agree to send

Goeben

to Constantinople and, subsequently, to send it alongside the Ottoman Navy into the Black Sea.

56

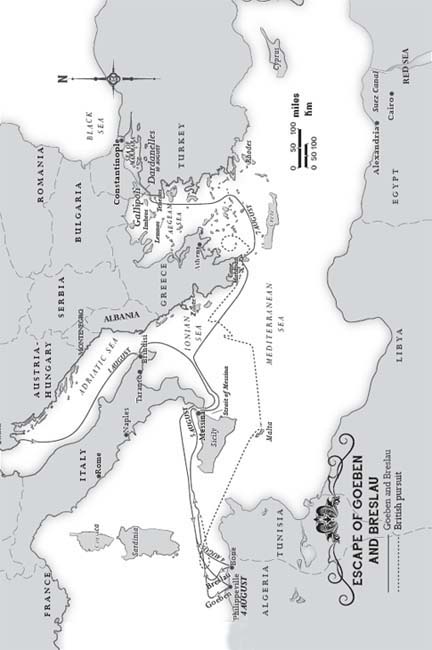

Escape of

Goeben

and

Breslau

, by Jane Macaulay

This news had been welcome then, but now that the stakes have risen, with war on the Western Front a reality, his request is problematic. The entry of these ships, in this manner, with the British in pursuit, will surely bring an end to Turkey's purported neutrality and spell war for the Ottomans. And their army is far from prepared.

âI can't decide that now,' he says in rapid staccato. âI must first consult the Grand Vizier.'

âBut,' von Kressenstein insists, âwe need to wire immediately.'

57

Enver takes a moment to think silently. The British Fleet will not be long in finding the ships where they lie, and if Turkey is to accept them, then it must be done now or never. There is a certain logic to it â¦

(As eyewitness to the moment, German military officer Colonel Hans Kannengiesser would later comment, âIt was a very difficult problem for Enver â usually so quick at arriving at a decision. He battled silently with himself though outwardly showed no signs of a struggle.')

58

He pauses. He deliberates. Is this the moment?

He draws himself up and says the words, âThey are to allow them to enter.'

Though relieved, the imperious von Kressenstein cannot resist following up. âIf the English warships follow the Germans,' he asks, âare they to be fired on if they also attempt an entrance?'

A second Rubicon beckons ⦠and, again, Enver is reluctant to cross it. âThe matter,' he says gravely, âmust be left to the decision of the Council of Ministers. The question can remain open for the time being.'

âExcellency,' von Kressenstein persists, âwe cannot leave our subordinates in such a position without issuing immediately clearly defined instructions. Are the English to be fired on or not?'

59

ââ¦

ââ¦

âYes â¦'

60

The German cruisers may enter.

The British ship will be stopped.

The Minister for War, General Enver, breaks the news to his Cabinet colleagues of what he has done, referring to

Goeben

with the smiling words, âA son has been born to us.'

61

With her forces not yet mobilised, âneutral' Turkey attempts to disguise this act of war â offering safe harbour for more than 24 hours to a ship of a combatant country â by proposing a sham purchase of the

Goeben

and

Breslau

. Germany agrees, the only condition being that, along with the warships, Admiral Souchon and his crew be drafted into the Ottoman Navy. So both warships will be claimed as Turkish; however, they will still remain firmly under German control. And while the Turks can

announce

their purchase of the ships, no actual sale can be made until the war is over and the Reichstag has approved it.

Genius!

The next morning, the Navy Minister, Cemal, releases an official communiqué, just two sentences long, announcing the news in the newspaper

Ikdam

: â

Osmanlılar! ⦠Müjde!

â Ottomans! ⦠Good news!

âThe Ottoman government purchased two German vessels, the

Goeben

and the

Breslau

, for 80 million marks. Our new vessels entered the straits at Chanak last evening. They will be in our port today.'

62

There is wild acclaim across Constantinople and other big cities. Though they were expecting news of their dreadnoughts from England, the edgy Ottomans are happy to be receiving these two brilliant new ships. And they are due to Constantinople that very day! We must get down to the shoreline to welcome them in.

The Turks have shown the English what they think of their treachery, taught them a lesson and made their navy stronger, all in one!

Ambassador von Wangenheim, meantime, has radioed Admiral Souchon â described by one contemporary as a âdroop-jawed, determined little man in a long-ill-fitting frock coat, looking more like a parson than an admiral'

63

â to tell him the news. Once the German ships get through the heads, they must immediately hoist the

Turkish

flag.

Ach, und noch was â¦

And one more thing.

The ships will soon no longer be

Goeben

and

Breslau

but

Yavuz Sultan Selim

and

Midilli

.

Later that morning, the American Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Henry Morgenthau â a lawyer from New York turned property speculator â drops in at the German embassy to find his German counterpart, Baron von Wangenheim, beside himself with excitement.

âSomething is distracting you,' Morgenthau says. âI will go and come back again some other time.'

âNo, no!' says the Baron. âI want you to stay right where you are. This will be a great day for Germany!'

A few minutes later, the blessed thing happens. The German Ambassador receives a radio message. âWe've got them!' he shouts to Morgenthau in his thick accent.

âGot what?'

âThe

Goeben

and the

Breslau

have passed through the Dardanelles.'

64

GETTING STARTED

Otherwise Australians shook their heads when they saw men of the first contingent about the city streets. âThey'll never make soldiers of that lot,' they would say. âThe Light Horse may be all right, but they've got the ragtag and bobtail of Australia in this infantry.'

1

Charles Bean, Official History of Australia in the War of 1914â1918

13 AUGUST 1914, THINGS CONTINUE TO SHAPE

In Melbourne, in his stone-walled office at Victoria Barracks on St Kilda Road, General Sir William Bridges is in the eye of the cyclone, personally calm and considered but making decisions that cause furious activity around the country as men continue to flood into recruiting depots.

By now, it has been established that existing territorial units will form the base of the Australian Expeditionary Force, which will be composed for the most part of volunteers in their 20th year and upwards. Ideally, while half of the force will have military experience, the other half will be trainees drawn from the universal training scheme and raring to go. All of them must be at least five foot six inches tall, with a chest measurement of at least 34 inches around the nipples to the back.

Initially, the AIF will comprise one large infantry division, the 1st Australian Division, composed of three brigades, with attendant units, and one Light Horse Brigade. Where possible, each brigade will be drawn from a particular state, its battalions from a particular district. Already, the government has started buying some of the 2300-odd horses thought necessary â most of them âWalers', a combined breed able to travel long distances in hot weather and go for as long as 60 hours without water, even while carrying a total load of over 20 stone! The government is also calling upon horse owners âto repeat the generosity shown during the Boer War and donate any horses suitable for military purposes'.

2

As to the manpower, while recruits are welcome from everywhere, including such institutions as Melbourne's Scottish Union â an umbrella group for Scottish clans and societies located in Victoria â General Bridges is very clear about one thing: âKilts could not be allowed. All Australian regiments must wear khaki, the only distinction being the colour of the hat-band â¦'

3

Oh. And one more thing ⦠Upon enlistment, some of the older recruits have the skin on their left chest examined to see if they bear tattoos of either BC or D. These are infamous old-time British Army tattoos, marking the bearer as either having Bad Character or being a Deserter.

In Constantinople, meanwhile, and indeed across the Ottoman Empire, there is all but equal activity as â led by Minister for War Enver and aided by the German Military Mission â there is an enormous effort to get the Turkish Armed Forces battle-ready against the growing likelihood that they, too, will soon be at war. Ammunition is produced and stockpiled, weaponry ordered and training of new recruits commenced with urgency.

This is no easy thing when, as an Empire of 23 million subjects, of whom just over half are Turks, they are âresource poor, industrially underdeveloped, and financially bankrupt',

4

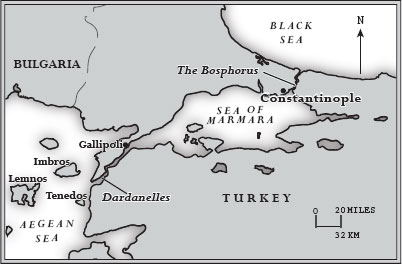

but at least the Turks themselves don't lack fervour. Despite the fact that the Ottoman Army is still not remotely recovered from the devastation of the Balkan Wars, despite the fact that the country's roads and railways, the telegraph network and the whole national infrastructure are antiquated, especially when compared with their European counterparts, still the army is capable of moving reasonably quickly via the key waterways â the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles â and it is the first and last that receive the first and last of its men and munitions.

The Black Sea, the Bosphorus, the Sea of Marmara and the Dardanelles, by Jane Macaulay

With Russia, as ever, the most likely threat to Turkey, detachments from the 1st Army Corps are ordered to the shores that lie at the northern end of the Bosphorus, as are torpedo boats. Down at the Dardanelles, the Bulair Battalion stationed near the town of Gallipoli had received mobilisation orders as early as the last day of July, and they are busily engaged in gathering troops and planning âtough and realistic battle training'.

5

Just the day before, the 9th Infantry Division's 26th Regiment at Gallipoli had reported its 2nd and 3rd Battalions at war strength. The Division's 27th Regiment have also reported for duty at war strength. Things are moving fast on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

19 AUGUST 1914, THE STREETS OF MELBOURNE THUNDER TO THEIR TREAD

Â

Far and near and low and louder

On the roads of earth go by,

Dear to friends and food for powder,

Soldiers marching, all to die.

6

A. E. Housman, A Shropshire Lad

Â

Here they come!

Ever and always, there is something magnificent about a large body of young men moving to the same rhythm, and this is a case in point. They are new recruits to the Australian Imperial Force, who have formed up at 9.30 this morning at Victoria Barracks, and are now âmarching' â at least the best they can â to the newly established camp at Broadmeadows, some ten miles away, to the north of the city. For the most part, the 2500 men â the nucleus of four battalions! â are still in the civilian clothes they were wearing when they signed up, but, gee, don't they look magnificent all the same! As they pass by Melbourne Town Hall, heading up Swanston Street, the only thing louder than the volunteer band â who, if you can believe it, are playing bugles and bagpipes at the same time â is the raucous cheering of the people.

And see how the pretty girls glow at them as they stride abreast, their chests puffed out as they gaily wave their hats to all their mates now gazing enviously upon them from office windows and roofs. They are now soldiers of the

King

, don't you know, heading away to

war

, to fight for the

Empire

! And the new recruits are so thrilled about it they all even wave happily at the men already becoming known as the âWould-to-God-ders' â those many men so often heard to say, âWould to God I could join myself, but â¦'

But there is no ill feeling at all now.

âIt was,' notes the

Age

's special war correspondent, Phillip F. E. Schuler, âthe first sight of the reality of war that had come to really grip the hearts of the people, and they cheered these pioneers and the recklessness of their spirits. There were men in good boots and bad boots, in brown and tan boots, in hardly any boots at all; in sack suits and old clothes, and smart-cut suits just from the well-lined drawers of a fashionable home; there were workers and loafers, students and idlers, men of professions and men just workers, who formed that force. But â they were all fighters, stickers, men with some grit (they got more as they went on), and men with a love of adventure.'

7

Finally, at 5 pm, they arrive at their âcamp', if that is what you can call row after row of tents hastily thrown up in dusty paddocks that stretch two miles wide by a mile and a half deep. âBedding,' one trooper records, âwas 2 blankets and a waterproof sheet â later came palliasses [mattresses] and straw.'

8

Their first port of call, even before heading to the âMess', is the quarter-master's store, where they are issued with khakis, webbing belts, packs, heavy brown boots and their first slouch hats â which they try on, oh so self-consciously. And then straight to the barbers to have their locks shorn.

Though you're not yet soldiers, not by a long shot, at least you bastards can start to

look

like soldiers.

From as soon as reveille the following morning, the grass in those paddocks starts to grow greener for the blood, sweat and tears those men expend in training ⦠before inevitably being killed off altogether and being ground into either dust or mud by the ceaseless tramp of feet. For now the men, in their newly issued kit, begin with â

âby the right, quiiiick march ⦠left, left, left, right, left'

â marching practice in their individual companies, and they soon progress to lessons in firing rifles for those few who don't already know how to do it. And then there are endless bayonet drills: how to sharpen it, attach it to your rifle and, most importantly, kill your enemy with it. The tummy is your best go, men â it's a big target, unshielded by any bones that will prevent you driving the blade right through your enemy, and a good strike will almost always prove fatal.

While that is the general thrust, the specifics are a lot more complex, and the man who is the Chief Bayonet Instructor at Broadmeadows, Captain Leopold McLaglen, is so expert on it he would later write a book so his expertise could be preserved. âWhen at close quarters with opponent, his equilibrium may be readily upset, thus placing you in position to deliver “Point”. From the cross rifle position force opponent's rifle to his left, dropping your bayonet on side of opponent's neck, your opponent naturally flinches to the right, his rifle being locked by your movement and your own body being guarded. At this moment place left foot at the side of the opponent's left foot, trip his left foot smartly to the left, at the same time forcing your bayonet downwards on opponent's neck â¦'

9

One of McLaglen's best students would prove to be a young fellow from down Geelong way by the name of Albert Jacka. Young and tough, he has been born and raised chopping wood, and though not a huge man, there is nothing of him that is not muscle, gristle and bone. While others soon tire at bayonet practice â all that shouting and stabbing at bags of straw â Jacka never does. He is âgreased lightning'!

10

Light and lithe, Jacka can put four holes in the bag in the time it takes other men to put in one, and already be onto the next bag and the one after that. As a little boy, he had been, his brother would later say, âvery, very bashful, though always ready to fight if anyone picked a quarrel'.

11

Though quite reserved, he intends to be ready to fight.

All of the new recruits now belong to the body of an entirely new order. You see, men, the base unit is a âsection', made up of a non-commissioned officer, like a Sergeant or a Corporal, a Lance-Corporal and 14 âprivates' at full strength. Three sections then make up a platoon, commanded by a Lieutenant; four platoons form a company of up to 227, commanded by a Major; four companies form the backbone of your battalion of 1017, under the command of a Lieutenant-Colonel; four battalions make a brigade of 4080; and three brigades totalling some 12,000 plus approximately 6000 supporting âdivisional troops' â artillery, signals, medical, transport (horses and wagons), engineers, etc. â make up the approximately 18,000 of the 1st Australian Division.

In command of a division is not God Himself, but not far off â usually a Major-General. When you put

two

divisions together with ancillary support units, you have an Army Corps.

As to those men training specifically with the Australian Light Horse, they learn that â unlike the âbeetle-crushers' (

sniff

) of the infantry â they are organised into brigades of about 1700 men each, composed of 546-strong regiments, consisting of three squadrons divided into troops of 32 Lighthorsemen divided in turn into eight sections of four men.

It could get very complicated, and for many of the new recruits the only safe way forward is to snap off myriad salutes at anyone with insignia indicating they aren't of your own lowly rank, and try to work out just what their military status and significance is later on â¦

Together with such skills training, there are frequent, sometimes daily, battalion parades, where the young soldiers have to turn up exactly on time, positively gleaming in their neatness, and then march and manoeuvre around the parade ground like clockwork. They must do such things as âForming Fours', whereby, through intricate manoeuvres of fancy footwork and many shouted orders â âBy Sections â Number!', âForm â Fours!', âTwo â Deep!'

12

â two long ranks of ten men become five short lines of four and permutations thereof in just a few seconds.

Of course, initially, the men are constantly getting it wrong, and of course the Drill Sergeant is constantly growling at the men â

âAs you were! As you WERE!' â

particularly once they graduate to the more complex forms such as Fours Wheeling and Forming Sections, but bit by bit it starts to come together.

But woe betide anyone who, on parade, does not have polished boots, shining brass and proper attire well presented. A mere unfastened button is enough for the Sergeant-Major to growl, âFall out, number three, and dress yourself â¦' And yes, number three does do that, usually âwith dragging step and unmistakable signs of disgust on his countenance',

13

but it is done.

It is all about imposing a discipline so that, in a battle, the soldier's instinct to obey a command from a superior officer is instant and automatic. In battle, they are told, there are âthe quick and the dead', and this training is about ensuring that they will be quick in both the response to the order and the execution of it. If an officer tells you to turn left, you turn left,

Suh!

; if he tells you to turn right, you turn right,

Suh!

; and if in battle he tells you to advance 50 yards and attack on the right flank, then that is what you do,

Suh!