Generation X (13 page)

"These are

my

parents, Dag. I know them better than that." But Dag is all too right, and accuracy makes me feel embarrassingly petty.

I parry his observation. I turn on him: "Fine comment coming from someone whose entire sense of life begins and ends in the year his own

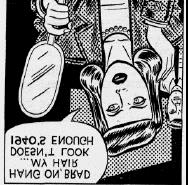

MUSICAL HAIRSPLITTING:

parents got married, as if that was the last year in which things could The act of

ever be safe. From someone who dresses like a General Motors showroom classifying music and musicians

into pathologically picayune

salesman from the year 1955. And Dag, have you ever noticed that your categories:

"The Vienna Franks

bungalow looks more like it belongs to a pair of Eisenhower era Allen-

are a good example of urban white

town, Pennsylvania newlyweds than it does to a fin de siècle existentialist

acid folk revivalism crossed with

ska."

poseur?"

"Are you through yet?"

1 0 1 -ISM: The tendency to

"No. You have Danish modern furniture; you use a black rotary-dial pick apart, often in minute detail,

all aspects of life using half-phone; you revere the Encyclopedia Britannica. You're just as afraid of understood pop psychology as a

the future as my parents." Silence.

tool.

"Maybe you're right, Andy, and maybe you're upset about going

home for Christmas—"

"Stop being nurturing. It's embarrassing."

"Very well. But

ne dump pas

on

moi,

okay? I've got my own demons and I'd prefer not to have them trivialized by your Psych 101-isms. We're always analyzing life too much. It's going to be the downfall of us all.

"I was going to suggest you take a lesson from my brother Matthew, the jingle writer. Whenever he phones or faxes his agent, they always haggle over who eats the fax—who's going to write it off as a business expense. And so I suggest you do the same thing with your parents. Eat

| them. Accept them as a part of getting you to here, and get on with life.

i Write them off as a business expense. At least your parents talk about Big Things. / try and talk about things like nuclear issues that matter to me with my parents and it's like I'm speaking Bratislavan. They listen I

indulgently to me for an appropriate length of time, and then after I'm out of wind, they ask me why I live in such a God-forsaken place like the Mojave Desert and how my love life is. Give parents the tiniest of confidences and they'll use them as crowbars to jimmy you open and

rearrange your life with no perspective. Sometimes I'd just like to mace them. I want to tell them that I envy their upbringings that were so clean, so free of

futurelessness.

And I want to throttle them for blithely handing over the world to us like so much skid -marked underwear."

PURCHASED

EXPERIENCES

DON'T

COUNT

"Check

that

out," says Dag, a few hours later, pulling the car over to the side of the road and pointing to the local Institute for the Blind.

"Notice anything funny?" At first I see nothing untoward, but then it dawns on me that the Desert Moderne style building is landscaped with enormous piranha-spiked barrel cactuses, lovely but razor deadly; vi sions of plump little

Far Side

cartoon children bursting like breakfast sausages upon impact, enter my head, fit's hot out. We're returning from Palm Desert, where

we drove to rent a floor

polisher, and on the way

back we rattled past

the Betty Ford Clinic

(slowly) and then past

the Eisenhower facility,

where Mr. Liberace

died. 'Hang on a sec-ond; I want to get a few

of those spines for the

charmed object collec-tion." Dag pulls a pair of

pliers and a Zip-Loc

plastic bag from the clapped-out glove box which is held closed with a bungie cord. He then jackrabbits across the traffic hell of Ramon

Road. Two hours later the sun is high and the floor polisher lies

exhausted on Claire's tiles. Dag, Tobias, and I are lizard lounging in the demilitarized zone of the kidney-shaped swimming pool central to our bungalows. Claire and her friend Elvissa are female bonding in my kitchen, drinking little cappuccinos and writing with chalks on my black wall, f A truce has been affected between the three of us guys out by the pool, and to his credit, Tobias has been rather amusing, telling tales of his recent trip to Europe—Eastern bloc toilet paper: "crinkly and shiny, like a K-Mart flyer in the

L.A. Times,"

and "the pilgrimage"—visiting the grave of Jim Morrison at the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris:

"It was super easy to find. People had spray painted 'This way to Jimmy's'

all over the tombstones of all these dead French poets. It was great."

Poor France.

Elvissa is Claire's good friend. They met months ago at Claire's doodad and bijou counter at I. Magnin. Unfortunately, Elvissa isn't her

real

name. Her real name is Catherine.

Elvissa

was my creation, a name that stuck from the very first time I ever used it (much to her pleasure) when Claire brought her home for lunch months ago. The name stems from

her large, anatomically disproportionate head, like that of a woman who points to merchandise on a TV game show. This head is capped by an

Elvis -oidal Mattel toy doll jet-black hairdo that frames her skull like a pair of inverted single quotes. And while she may not be

beautiful

per se, like most big-eyed women, she's compelling. Also, in spite of living i n t h e d e s e r t , s h e ' s a s p a l e a s c r e a m c h e e s e a n d s h e ' s a s t h i n a s a g r e y h o u n d c h a s i n g a p a c e b u n n y . S u b s e q u e n t l y , she will seem a little bit cancer prone.

Although their background orbits are somewhat incongruous, Claire

and Elvissa share a common denominator—both are headstrong, both

have a healthy curiosity, but most important, both left their old lives behind them and set forth to make new lives for themselves in the name of adventure. In their similiar quest to find a personal truth, they willingly put themselves on the margins of society, and this, I think, took some g u t s . I t ' s h a r d e r f o r w o m e n t o d o t h i s t h a n m e n .

Conversation with Elvissa is like having a phone call with a noisy

child from the deep South—Tallahassee, Florida, to be exact—but a child speaking from a phone located in Sydney, Australia, or Vladivostok in the USSR. There's a satellite time lag between replies, maybe one-tenth of a second long, that makes you think there's something suspect malfunctioning in your brain—information and secrets being withheld from you.

As for how Elvissa makes her living, none of us are quite sure,

and none of us are sure we want to even

know.

She is living proof of Claire's theory that anyone who lives in a resort town under the age of thirty is on the make. I

think

her work may have to do with pyramid or Ponzi schemes, but then it may be somehow sexual: I once saw her in a Princess Stephanie one-piece swimsuit ("please, my

maillot")

chatting amiably with a mafioso type while counting a wad of bills at the poolside of the Ritz Carlton, high in the graham cracker—colored hills above Rancho Mirage. Afterward she denied she was there.

When pressed,

she will admit to selling never-to-be-seen vitamin shampoos, aloe products, and Tupper- ware containers, on which subject she is able to improvise convincing antiweevil testimonials on the spot ('This crisper saved my

life").

Elvissa and Claire exit my bungalow. Claire appears both depressed

and preoccupied, eyes focused on an invisible object hovering above the ground a body's length in front of her. Elvissa, however, is in a pleasant state and is wearing an ill-fitting 1930s swimsuit, which is her attempt to be hip and retro. In Elvissa's mind this afternoon is her "time to be Young and do Young things with Young people my own age." She thinks of us as Youngsters. But her choice of swimwear merely accen-tuates how far removed she has become from current bourgeois time/

space. Some people don't have to play the hip game; I like Elvissa, but s h e c a n b e s o c l u e d o u t .

"Check out the Vegas housewife on chemotherapy," whispers To-bias to me and Dag, misguidedly trying to win our confidence through dumb wisecracks.

"We love you, too, Tobias," replies Dag, after which he smiles up at the girls and says, "Hi, kids. Have a nice chat?" Claire listlessly grunts and Elvissa smiles. Dag hops up to kiss Elvissa while Claire flops out on a sun-bleached yellow fold-out deck chair. The overall effect around the pool is markedly 1949, save for Tobias's Day-Glo green

swimsuit.

"Hi, Andy," Elvissa whispers, bending down to peck me on the cheek. She then mumbles a cursory hello to Tobias, after which she

grabs her own lounger to begin the arduous task of covering every pore of her body with PABA 29, her every move under the worshipful looks of Dag, who is like a friendly dog unfortunately owned by a never-at-home master. Claire's body on the other side of Dag is totally rag-doll slack with gloom. Did she receive bad news, or something?

(Perish the thought.)

"Spare me,

please."

retaliates Elvissa. "I know your type exactly.

You yuppies are all the same and I am fed up indeed with the likes of you. Let me s e e y o u r e y e s . "

" W h a t ? "

YUPPIE WANNABE'S:

"Let me see your eyes."

An

X

generation subgroup that

Tobias leans over to allow Elvissa to put a hand around his jaw

believes the myth of a yuppie

life-style being both satisfying

and extract information from his eyes, the blue color of Dutch souvenir and viable. Tend to be highly in

plates. She takes an awfully long time. "Well, okay. Maybe you're not debt, involved in some form o f

all

t h a t

bad. I

m i g h t

even tell you a special story in a few minutes.

substance abuse, and show a

willingness to talk about

Remind me. But it depends. I want you to tell me something first: after Armageddon after three drinks.

you're dead and buried and floating around whatever place we go to, what's going to be your best memory of earth?"

" W h a t d o y o u m e a n ? I d o n ' t g e t i t . "

"What one moment for you defines what it's like to be alive on this p l a n e t . W h a t ' s y o u r

t a k e a w a y ? "

There is a silence. Tobias doesn't get her point, and frankly, neither do I. She continues: "Fake yuppie experiences that you had to spend money on, like white water rafting or elephant rides in Thailand don't count. I want to hear some small moment from your life that

proves you're

really alive."

Tobias does not readily volunteer any info. I think he needs an

example first.

" I've got one," says Claire.

A l l e y e s t u r n t o h e r .

" S n o w , " s h e s a y s t o u s . " S n o w . "

E M E M B E

EARTH

CLEARLY

"Snow," says Claire, at the very moment a hailstorm of doves erupts upward from the brown silk soil of the MacArthurs' yard next door.

The MacArthurs have been trying to seed their new lawn all week, but the doves just love those tasty little grass seeds. And doves being so cute and all, it's impossible to be genuinely angry with them. Mrs.

Mac Arthur (Irene) halfheartedly shoos them away every so often, but the doves simply fly up on top of the roof of their house, where they consider t h e m s e l v e s h i d d e n , a t

w h i c h p o i n t t h e y t h r o w

exciting little dove parties.

I'll always remember

the first time I saw snow.

I was twelve and it

w a s j u s t a f t e r t h e f i r s t

and biggest divorce. I

was in New York visit -ing my mother and was

standing beside a traffic

island in the middle of

P a r k A v e n u e . I ' d n e v e r

been out of L.A. before.

I was entranced by the big city. I was looking up at the Pan Am Building and contemplating the essential problem of Manhattan." 'Which is —?" I ask. "Which is that there's too much weight improperly distributed: t o w e r s a n d e l e v a t o r s ; s t e e l , s t o n e , a n d c e m e n t . S o m u c h

mass

u p s o high that gravity itself could end up being warped—some dreadful

inversion—an exchange program with the sky." (I love it when Claire gets weird.) "I was shuddering at the thought of this. But

right then

my brother Allan yanked at my sleeve because the walk signal light was green. And when I turned my head to walk across, my face went

bang,

right into my first snowflake ever. It melted in my eye. I didn't even know what it

was

at first, but then I saw

millions

of flakes—all white and smelling like ozone, floating downward like the shed skins of angels.

Even Allan stopped. Traffic was honking at us, but time stood still. And so,

yes

—if I take

one

memory of earth away with me, that moment will be the one. To this day 1 consider my right eye charmed."

"Perfect," says Elvissa. She turns to Tobias. "Ge t the drift?"

"Let me think a second."

"I've got one," says Dag with some enthusiasm, partially the result, I suspect, of his wanting to score brownie points with Elvissa. "It hap-pened in 1974. In Kingston, Ontario." He lights a cigarette and we wait.

"My dad and I were at a gas station and 1 was given the task of filling up the gas tank—a Galaxy 500, snazzy car. And filling it up was a big responsibility for me. I was one of those goofy kids who always got colds and never got the hang of things like filling up gas tanks or unraveling tangled fishing rods. I'd always screw things up somehow; break some -t h i n g ; h a v e i t d i e .

"Anyway, Dad was in the station shop buying a map, and I was

outside feeling so manly and just

so

proud of how I hadn't botched anything up yet—set fire to the gas station or what have you—and the tank was a/most full. Well, Dad came out just as I was topping the tank off, at which point the nozzle simply went nuts. It started spraying all over. I don't know why—it just

d i d

—all over my jeans, my running shoes, the license plate, the cement—like purple alcohol. Dad saw

everything and I thought I was going to catch total shit. I felt so small.

But instead he smiled and said to me, 'Hey, Sport. Isn't the smell of gasoline great? Close your eyes and inhale. So

clean.

It smells like the

future.

'

"Well, I did that—I closed my eyes just as he asked, and breathed i n d e e p l y . A n d a t t h a t p o i n t I s a w t h e b r i g h t o r a n g e l i g h t o f t h e s u n coming through my eyelids, smelled the gasoline and my knees buckled.

But it was the most perfect moment of my life, and so if you ask me (and I have a lot of my hopes pinned on this), heaven just

has

to be an awful lot like those few seconds. That's my memory of earth."

" W a s i t l e a d e d o r u n l e a d e d ? " a s k s T o b i a s .

"Leaded," re p l i e s D a g .

"Perfect."

" A n d y ? " E l v i s s a l o o k s t o m e . " Y o u ? "

"I know my earth memory. It's a smell—the smell of bacon. It was a Sunday morning at home and we were all having breakfast, an un-precedented occurrence since me and all six of my brothers and sis ters inherited my mother's tendency to detest the sight of food in the morning.

W e ' d s l e e p i n i n s t e a d .

"Anyhow, there wasn't even a special reason for the meal. All nine of us simply ended up in the kitchen by accident, with everyone being funny and nice to each other, and reading out the grisly bits from the n e w s p a p e r . I t w a s s u n n y ; n o o n e w a s b e i n g p s y c h o o r m e a n .

"I remember very clearly standing by the stove and frying a batch o f b a c o n . I k n e w e v e n t h e n t h a t t h i s w a s t h e o n l y s u c h m o r n i n g o u r family would ever be given—a morning where we would all be normal

and kind to each other and know that we liked each other without any strings attached—and that soon enough (and we did) we would all be-come batty and distant the way families invariably do as they get along in years.

"And so I was close to tears, listening to everyone make jokes and feeding the dog bits of egg; I was feeling homesick for the event while it was happening. All the while my forearms were getting splattered by little pinpricks of hot bacon grease, but I wouldn't yell. To me, those pinpricks were no more and no less pleasurable than the pinches my

sisters used to give me to extract from me the truth about which one I l o v e d t h e m o s t—and it's those little pinpricks and the smell of bacon that I'm going to be taking away with me; that will be my memory of earth."

Tobias can barely contain himself. His body is poised forward, like a child in a shopping cart waiting to lunge for the presweetened breakfast cereals: "I know what my memory is! I know what it is now!" "Well j u s t

t e l l

u s , t h e n , " s a y s E l v i s s a .

"It's like this —" (God only knows what

it

will be) "Every summer back in Tacoma Park" (Washington, D.C. I

knew

it was an eastern city)

"my dad and I would rig up a shortwave radio that he had left over from the 1950s. We'd string a wire across the yard at sunset and tether it up to the linden tree to act as an antenna. We'd try all of the bands, and if the radiation in the Van Allen belt was low, then we'd pick up just about everywhere: Johannesburg, Radio Moscow, Japan, Punjabi stuff.

But more than anything we'd get signals from South America, these weird haunted-sounding bolero-samba music transmissions from dinner thea-

ULTRA SHORT TERM

ters in Ecuador and Caracas and Rio. The music would come in

NOSTALGIA:

Homesickness

faintly—faintly but clearly.

for the extremely recent past:

"God, things seemed so much

"One night Mom came out onto the patio in a pink sundress and

better in the world last week."

carrying a glass pitcher of lemonade. Dad swept her into his arms and they danced to the samba music with Mom still holding the pitcher. She was squealing but loving it. I think she was enjoying that little bit of danger the threat of broken glass added to the dancing. And there were crickets cricking and the transformer humming on the power lines behind the garages, and 1 had my suddenly young parents all to myself—them and this faint music that sounded like heaven—faraway, clear, and

impossible to contact—coming from this faceless place where it was

always summer and where beautiful people were always dancing and

where it was impossible to call by telephone, even if you wanted to.

Now

t h a t ' s

earth to me."

Well, who'd have thought Tobias was capable of such thoughts?

W e ' r e g o i n g t o h a v e t o d o a r e e v a l u a t i o n o f t h e l a d .

"Now you have to tell me the story you promised," says Tobias to Elvissa, who seems saddened by the prospect, as though she has to keep a b e t s h e r e g r e t s h a v i n g m a d e .

"Of course. Of course I will," she says, "Claire tells me you people t e ll stories sometimes, so you won't find it too stupid. You're

none

of you allowed to make any cracks, okay?"

"Hey," I say, "that's always been our main rule."

CHANGE

COLOR

Elvissa starts her tale: "It's a story I call The Boy with the Hummingbird Eyes." So if all of you will please lean back and relax now, I will tell it. 'lt starts in Tallahassee, Florida, where I grew up. There was this boy next door, Curtis, who was best friends with my brother Matt. My mother called him Lazy Curtis because he just drawled his way through life, rarely speaking, silently chewing bologna sandwiches inside his lantern jaw and hitting baseballs farther than anyone else whenever he g o t u p t h e w i l l t o d o s o .

H e w a s j u s t

s o

w o n d e r-fully silent. So competent at everything. I, of

course, madly adored

Curtis ever from the first

moment our U-haul

pulled up to the new

house and I saw him

lying on the grass next

door smoking a cigarette,

an act that made my

m o t h e r j u s t a b o u t f a i n t .

He was maybe only

fifteen. "I promptly copied everything about him. Most superficially I copied his hair (which I still indirectly feel is slightly his to this day), h i s s l o p p y T -shirts and his lack of speech and his panthery walk. So did my brother. And the three of us shared what are still to me the best times of our lives walking around the subdivision we lived in, a devel-opment that somehow never got fully built. We'd play war inside these tract houses that had been reclaimed by palm trees and mangroves and small animals that had started to make their homes there, too: timid a well-cut head of black hair and a hot bod. He would also occasionally bob his head up and down, then sideways, not like a spastic, but more as though he kept noticing something sexy from the corner of his eyes but was continually mistaken.

"Anyhow, this rich broad, this real

Sylvia

type" (Elvissa calls rich women with good haircuts and good clothes

Sylvias)

"comes out from the spa building going mince mince mince with her little shoey-wooeys and her Lagerfeld dress, right up to this guy in front of me. She purrrrs something I miss and then puts a little gold bracelet around this guy's wrist which he offers up to her (body language) with about as much

enthusiasm as though he were waiting for her to vaccinate it. She gives the hand a kiss, says 'Be ready for nine o'clock' and then toddles off.

"So I'm curious.

"Very coolly I stroll over to the pool bar—the one you used to work i n , A n d y —and order a most genteel cocktail of the color pink, then saunter back to my perch, surreptitiously checking out the guy on the way back. But I think I died on the spot when I saw who it was. It was Curtis, of course.

"He was taller than I remembered, and he'd lost any baby fat he m i g h t h a v e h a d , and his body had taken on a sinewy, pugilistic look, like those kids who shop for needle bleach on Hollywood Boulevard who sort of resemble German tourists from a block away and then you see them up close. Anyhow, there were a lot of ropey white scars all over him. And Lord! The boy had been to the tattoo parlor a few times. A crucifix blared from his inner left thigh and a locomotive engine roared across his left shoulder. Underneath the engine there was a heart with china-d i s h b r e a k m a r k s ; a b o u q u e t o f dice and gardenias graced the o t h e r s h o u l d e r . H e ' d o b v i o u s l y b e e n a r o u n d t h e b l o c k a f e w t i m e s .

"I said, 'Hello, Curtis.' and he looked up and said, 'Well I'll be damned! It's Catherine Lee Meyers!' 1 couldn't think of what to say next.

I put down my drink and sat closed legged and slightly fetal on a chair beside him and stared and felt warm. He reached up and kissed me on t h e c h e e k a n d s a i d , ' I m i s s e d y o u , B a b y D o l l . T h o u g h t I ' d b e d e a d before 1 ever saw you again.'

"The next few minutes were a blur of happiness. But before long I had to go. My client was calling. Curtis told me what he was doing in town, but I couldn't make out details —something about an acting job in L.A. (uh oh). But even while we were talking, he kept bobbing his head around to and fro looking at I don't know what. I asked him what he was looking at, and all he said was 'hummingbirds. Maybe I'll tell you more tonight.' He gave me his address (an apartment address, not a hotel), and we agreed to meet for dinner that night at eight thirty. I couldn't really say to him,

' B u t w h a t a b o u t S y l v i a ? '

really

c o u l d I ,

knowing that she had a nine o'clock appointment. I didn't want to seem snoopy.

"Anyhow, eight thirty rolled around, plus a little bit more. It was t h e n i g h t o f t h a t s t o r m—remember tha t ? I j u s t

b a r e l y

made it over to the address, an ugly condo development from the 1970s, out near Rac-quet Club Drive in the windy part of town. The power was out so the streetlights were crapped out, too. The flash-flood wells in the streets were beginning to overflow and I tripped coming up the stairs of the apartment complex because there were no lights. The apartment, number three-something, was on the third floor, so I had to walk up this pitch-black stairwell to get there, only to be ignored when I knocked on the door. I was furious. As I was leaving, I yelled

' Y o u h a v e g o n e t o t h e

dogs, Curtis Donnely,'

at which point, hearing my voice, he opened the door.