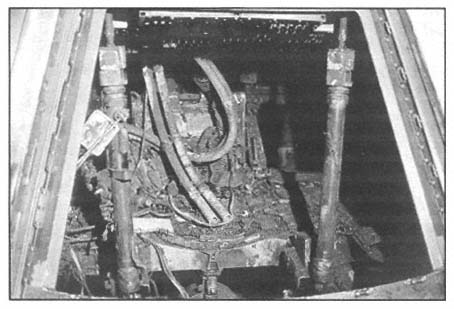

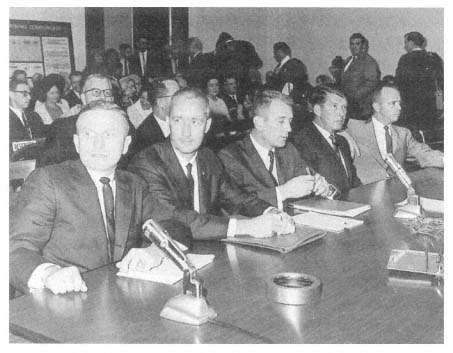

communication tapes of the accident, listening to the anguished scream of Roger Chaffee crying, "We're burning up!" in an effort to find out what happened.

|

The astronauts' deaths destroyed the lives and careers of several people at NASA. One man had a nervous breakdown. Borman, however, saw it no differently than the many other deaths he had witnessed while he was a test pilot. This was risky work, and people sometimes died doing it.

|

Nonetheless, Borman felt himself getting increasingly angry. Everywhere he and the rest of the investigation committees looked, they found sloppy workmanship by both the contractor and by NASA.

|

When Borman had been a freshman at West Point, something had happened that would define the rest of his life. The plebe's life was brutal: up at dawn, working sixteen hours a day, little time off, and little sympathy from anyone. One day the cadets had been running the plebes around all day, doing twenty-mile hikes, endless drills, and continuous workouts.

|

The day ended with bayonet drills on the West Point grounds. The plebes made repeated forward thrusts with their bayoneted rifle, holding it out at full stretch as if they had just stuck it in the gut of an enemy soldier. Never a big man, Borman only weighed one hundred forty pounds when he was eighteen. Now he was literally trembling with exhaustion. He couldn't hold the rifle steady.

|

Observing the plebe with contempt was a small, wiry lieutenant colonel who was actually a bit shorter than Borman. The officer came up to Frank and began screaming at him, telling him that he couldn't back it, that he wasn't good enough.

|

Borman stopped trembling. He grew both calm and angry and looked that "little weasel" in the eye. No bastard was going to tell him he couldn't do something. He might be a naïve, country boy suddenly thrust into the hard, competitive world of West Point, but they'd have to kill him to get him out of the Academy. It was the same determination and strength of will that allowed him to bring every plane he ever flew safely back to earth.

|

Now, twenty years later, it was the same thing. Borman decided that he was going to do whatever it took to make sure the Apollo spacecraft flew again. And when it did, it would be the safest spacecraft ever built.

|

|