Genius on the Edge: The Bizarre Double Life of Dr. William Stewart Halsted (24 page)

Read Genius on the Edge: The Bizarre Double Life of Dr. William Stewart Halsted Online

Authors: Gerald Imber Md

Tags: #Biography & Autobiography, #Medical, #Surgery, #General

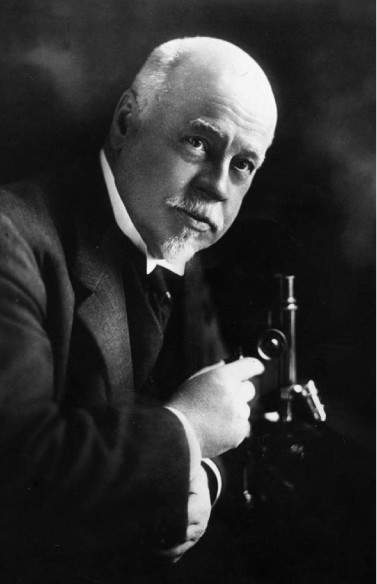

William Halsted, circa 1904, at High Hampton.

William H. Welch, 1905, the first dean of John Hopkins’s medical school.

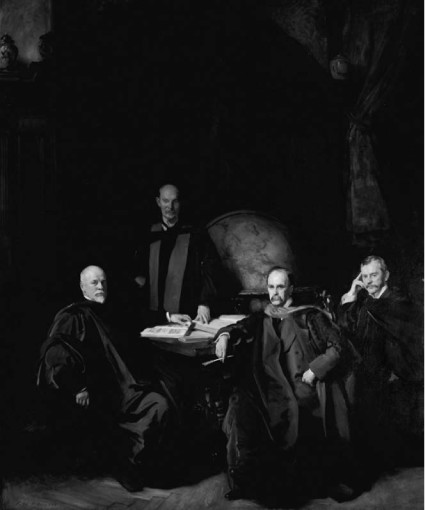

The Four Doctors

by John Singer Sargent, 1906. From left, Welch, Halsted (standing), Osler, and Kelly.

High Hampton, the Halsteds’ country home in North Carolina, circa 1920.

Interior of High Hampton, circa 1920.

Halsted and his early associates and residents, October 1914. Standing, from left:

Roy McClure, Hugh Young, Harvey Cushing, James Mitchell, Richard Follis, Robert Miller,

John Churchman, and George Heuer. Seated: John M.T. Finney, Halsted, Joseph Bloodgood.

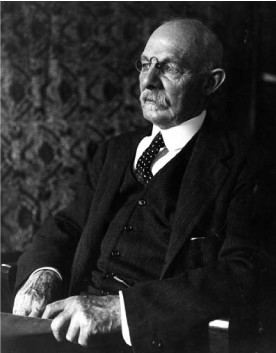

Franklin P. Mall, a famous anatomy professor and one-time laboratory mate of William Halsted, 1911.

William Halsted studying X-Ray, 1914.

William Halsted, 1922. Photograph by John H. Stockdale.

CHAPTER NINETEEN

Country Squire

FROM THE TIME OF

their honeymoon trip in 1890, the Cashiers Valley in the Blue Ridge Mountains became central to the Halsteds’ life together. In 1895, Halsted arranged to purchase the Hampton family lodge and the remaining 450 acres from Caroline’s aunts. Whether implicit in the transaction or not, “the aunties” became relatively permanent guests, and Caroline’s sisters and their children often visited as well. Over the following years Halsted annexed contiguous lands and small farms, until the estate grew once again to more than 2,000 acres.

Halsted’s acquisition of the properties usually suited the purposes of both parties, and he was seen as a great benefactor to the hard-scrabble community. But the purchase of an adjoining 50-acre farm in 1897 ended sadly, and resulted in the story of “The White Owl of High Hampton.” The tragic tale was often retold in the Cashiers community and memorialized in a painting. As the story goes, Halsted had made an offer to the farmer, Hannibal Heaton, who was amenable to the sale. His wife was not. She became extremely upset and threatened to kill herself if he sold their home. Heaton did not abide her wishes or her threat, and upon returning from completing the transaction found his wife hanging from an oak tree near the house. Legend has it that

in the air, circling her head, was a white owl, eerily screeching like a crying woman. Heaton left and never returned to the Cashiers Valley; his wife was buried at the cemetery on the High Hampton property.

Over the years the Halsteds continued to negotiate land purchases through their Charleston attorney, Frank R. Frost. The largest of these was a 640-acre parcel acquired from the heirs of the Preston family at a price of one dollar an acre. Offers made for other nearby land were as low as twenty-five cents an acre.

AS THE LAND ACQUISITIONS

restored their control of the valley, the Halsteds began the long process of upgrading the long-neglected buildings. Another cottage was added, along with a guesthouse, both in the unpainted clapboard style of the lodge, which was itself improved in functional ways such as the construction of a pipeline and pump to supply fresh water. The rooms were comfortable and anything but elegant. Furnishings were spare, primarily wicker and wood, and quite unlike the clutter of expensive antiques strewn about the Baltimore house.

The main house and the guest cabins were closely grouped and in the shade of great, old trees. Paths between them were cut and edged, and the immediate grounds were neatly tended. Hiking and riding trails were rough and natural, and often subject to flooding and fallen trees.

The view of the mountains was dramatic. The glittering granite escarpments and waterfalls of Whiteside and Chimney Top mountains, the two highest peaks in the range, were clearly visible, and were as awe-inspiring as any picture postcards. Between the houses and the distant view was a small lake stocked with trout, fast-running streams, and rough-hewn riding trails. Halsted’s dahlia garden was located close to the house, and farther away were many acres planted with basic crops such as corn, potatoes, and turnips grown for both human and animal consumption. Yield was plentiful in the rich soil,

but the demand so thin that Halsted once wrote, “Our potato crop is so great that we are embarrassed to know what to do with it.”

Caroline took an active hand in the farming, often helping with the planting and picking, once bagging 450 bushels of rutabaga with only her young cook to help. A half dozen hands regularly worked the place under longtime farm manager Douglas Bradley, and there was always too much to do. In addition to routine tasks, Caroline oversaw the building of a sawmill to provide finished lumber for their building needs, as well as a water-powered grist mill that turned out excellent stone-ground meal. She supervised the cutting of trails and logging, the care of the farm animals, and personally looked after her constant companions, the family dogs.

For Halsted, High Hampton was a place to read, relax, and indulge in activities he had little time for in the city. Health permitting, he was always available for a hike, a horseback ride, or a drive in the buckboard or buggy. His farming activities were restricted to choosing and cutting dahlias and picking corn. Corn on the cob, freshly picked while the water was set to boil, was a favorite lunchtime treat, and he had perfected a system for determining ripeness that regularly dazzled visitors. Walking among the lines of corn with drying silk, he would roll the ears between his fingers and feel for a telltale crunch that indicated the corn was ready for picking.

Caroline was in charge of projects large and small, and despite its identification with her husband, she was the primary caretaker of Halsted’s prized dahlia garden. She arrived at High Hampton in early spring and left in November, the prescribed times for planting new tubers and digging up and separating the old. Each winter Halsted scoured the European seed catalogues and garden literature and ordered the most interesting new dahlia varieties. These would arrive at Cashiers long before he, and Caroline would have the beds prepared and the tubers planted in wide military rows separated by grass paths. The flowers were usually in bloom by Halsted’s arrival, and by

midsummer they were eye height and bursting with huge heads of brilliant color. Though he had little hand in the care and feeding of his precious garden, Halsted was responsible for choosing the plants for each year’s color show. He thoroughly enjoyed the spectacle and in early morning would walk the grass path between the beds, often still in pajamas, robe, and slippers. George Heuer was a guest on a particularly moist morning when the legs of Halsted’s pajamas became soaked with dew and clung to his legs. Caroline, already dressed in her usual short, heavy skirt and boots, spotted him from the veranda and called out, “William, how many times have I told you not to go out like that? Look at your slippers, they are soaking wet.”