Georgian London: Into the Streets (18 page)

Read Georgian London: Into the Streets Online

Authors: Lucy Inglis

Drowning was a preoccupation among the medical pioneers of London. They knew there was a relationship between the cessation of breathing and the stopping of the heart.

John Hunter had conducted

gory experiments on a dog by removing the sternum of a living animal to observe what happened to the heart when breathing

was severely restricted by use of a bellows mechanism. This prompted him to design a machine, again based on a bellows, which would restart the breathing in apparently drowned individuals. His paper, presented to the Royal Society in 1776, was full of good sense: he had observed that cold water often kept people alive for longer than if they were ‘drowned’ in warmer water, and that they should only be warmed up slowly. He did, however, think that blowing air up the anus might also be beneficial for the drowned. A mixed bag.

Nevertheless, Hunter’s paper coincided with popular interest in resuscitation: ideas of ‘artificial breathing’ aided by bellows, or mouth to mouth, were gaining ground and the rudiments of cardiac massage were emerging.

For five years before Hunter’s

influential paper, an Islington-born doctor, William Hawes, had been agitating for funding and action to be taken for ‘the resuscitation of people apparently dead’. In 1773, in his ‘incessant zeal’ to prove that it was possible to bring back the drowned from the edge of death, he organized and paid for ‘reception houses’ between Westminster and London Bridges where people could be brought ‘within a certain time after the accident’ and attempts would be made to resuscitate them. By summer 1774, he and the other doctors staffing the reception houses had been so successful that they met with a group of philanthropists including playwright Oliver Goldsmith in the Chapter Coffee House in St Paul’s Churchyard and formed the Society for the Recovery of Persons Apparently Drowned.

The Society provided training in the new rescue techniques. In July of the same year, Thomas Vincent, a waterman, rescued a fourteen-month-old boy from an aqueduct and revived him using the massage techniques. In 1776, the Society changed its name to the Humane Society. Levels of public approval for reanimating those who had previously been thought lost were already high, as reported in the

Morning Chronicle

in January that year: ‘

As proof

that the Society for the Recovery of Drowned Persons is well received by the publick, the Debating Society at the Crown Tavern in Bow lane where every subject is fully discussed, have given 5 guineas as a token of their approbation.’

Hawes and his colleagues continued to refine their methods of

reviving the drowned by expelling water from the lungs and beating rhythmically upon the victims’ chests. In the same year, William Henly, a Fellow of the Royal Society, wrote to the Humane Society with a suggestion that electricity be used to shock the heart and brain in ‘

cases of Apparent Death from Drowning’. After all, he reasoned, why not use ‘the most potent resource in nature, which can instantly pervade the innermost recesses of the animal frame’? In 1794, the first clear success in using electricity to restart the heart was recorded by what had become the Royal Humane Society. Sophia Greenhill, a young girl, had fallen from a window in Soho and was pronounced dead by a doctor at Middlesex Hospital. Mr Squires, a local member of the Society, made it to the girl in around twenty minutes. Using a friction-type electricity machine, he applied shocks to her body. It seemed ‘in vain’, until he began to shock her thorax. Then he felt a pulse, and the child began to breathe again. She was concussed but went on to make a full recovery, and the Royal Humane Society was finally sure of the importance of electricity in reanimating those in ‘suspended animation

’.

In the same year, George III – who was already a patron of the Society – gave land on the north bank of the Serpentine for a headquarters and principal receiving house to be erected. Lifeguards were stationed there, who were trained in the latest techniques of resuscitation and in using equipment for restoring respiration and pulse. By the early Victorian period, there were eighteen receiving houses in London, and the

Illustrated London News

estimated some 200,000 people were bathing in the Serpentine each year. In winter, the lifeguards donned greatcoats emblazoned with ‘Iceman’ on the back and patrolled the banks for any skater who might fall through the ice. Icemen operated throughout London at all regular skating grounds.

The success rate of the Royal Humane Society’s operatives was undeniable. They were required never to drink on the job, and were made aware of the complications in rescuing suicides and working in icy conditions with hypothermic subjects. They couldn’t always win, of course. In 1816, Percy Bysshe Shelley’s wife, Harriet, drowned herself in the Serpentine after he had abandoned her for Mary Godwin.

At the end of the Georgian period, in 1834, the Serpentine receiving house was given a grand makeover, with the Duke of Wellington laying the foundation stone. The Royal Humane Society had taught resuscitation techniques to many Londoners, and the Society’s receiving houses formed the earliest model for what became Accident and Emergency departments. Lifeguards and icemen had become familiar sights, patrolling the Serpentine. Whereas at the beginning of the century chances of survival for those thought drowned were almost non-existent, by the end of the Georgian period the Society’s operatives had learned to do everything they could because, in the words of their motto, ‘a small spark may perhaps lie hid’.

For all their grandeur and undoubted importance, Westminster and St James’s retained a variety and humanity which seem removed from them now. Boozing politicians, campaigning ladies, weight-conscious poets and Herculean chairmen mixed in with art, philanthropy and science. These areas also fuelled the luxury goods and entertainment industries which were growing rapidly in nearby Covent Garden and Soho. Next, we will visit some of the less polite attractions of Georgian London.

4. Bloomsbury, Covent Garden and the Strand

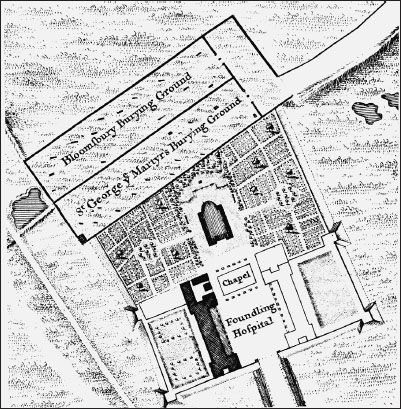

For a long time, Bloomsbury was part of the parish of St Giles-in-the-Fields. In 1624, Bloomsbury had 136 houses; by 1710, a return was made to Parliament which indicated that St Giles alone contained almost 35,000 inhabitants catered for by one church, three chapels and a Presbyterian Meeting House. The government decided to create a new parish to the north. In 1724, it came into being as St George’s, Bloomsbury. The parish church was designed by Nicholas Hawksmoor, who came in with an estimate of £9,790 and exceeded it by just £3. It was orientated north–south, to fit the plot, and has an oddly stepped steeple with a statue of George I on the top.

By the end of the eighteenth century

, the parish contained 3,000 houses.

The changes in Bloomsbury were remarkable and some of the most dramatic in Georgian London: ‘

The fields where robberies and murders had been committed, the scene of depravity and wickedness the most hideous for centuries, became … rapidly metamorphosed into splendid squares and spacious streets; receptacles of civil life and polished society.’ Previously, north of Holborn, there had been little other than marshy fields (where gentlemen held ill-advised duels), a few farms and some taverns, such as the Vine Tavern which sat at the bottom of Kingsgate Street on the site of London’s ancient and only vineyard. The nearby Maidenhead Inn, which was probably named sarcastically, flourished as ‘a liquor-shop and public house of the vilest description, and the haunt of beggars and desperate characters

’. These were the places that the citizens of Bloomsbury wanted to see fade away.

In Bloomsbury Place, the seeds of a British institution were sown when Hans Sloane opened his medical practice after a trip to Jamaica. Jamaica had cemented his love of natural history and the exotic, and he began to establish his reputation as a naturalist. His ferocious love of collecting, and the large income from his practice, meant that he soon had the basis for a museum, and he bought a neighbouring

house to accommodate his objects. As he aged, he became more disorganized – though he still collected greedily. The young botanist Carl Linnaeus visited and was shocked by Sloane’s lack of order. Upon Sloane’s death, in 1753, his trustees offered the collection to George II, to no avail. Instead, the trustees petitioned Parliament, and the collection was secured for the nation. The nation had also acquired Edward Harley’s library and the Cotton Library, and they too needed a new home. The aging Montagu House, a short distance from Sloane’s old home on Bloomsbury Place, was acquired for the purpose. Renamed the ‘British Museum’, it opened on 15 January 1759. Tickets were by application, and they stated that ‘No Money is to be Given to the Servants’, who had no doubt hoped to make handsome tips showing visitors around.

Three years after the British Museum was given the royal seal of approval, another temple to education emerged in Bloomsbury: University College. It had long been observed that London had no true university to rival those of Oxford and Cambridge. Jeremy Bentham, the philosopher and legislator, along with Lord Brougham and the poet Thomas Campbell, wanted to create an institution which would deliver a ‘

literary and scientific

education at a moderate expense’.

All this was within a stone’s throw of Southampton Row, one of Bloomsbury’s oldest streets, and the long-time residence of another Bloomsbury character, Mrs Griggs. Upon her death, in 1792, the

Annual Register

remembered her as

… [that] eccentrical lady … at her house, Southampton Row, Bloomsbury, Mrs. Griggs. Her executors found in her house eighty-six living and twenty-eight dead cats. A black servant has been left £150 per annum, for the maintenance of herself and the surviving grimalkins. The lady was single, and died worth £30,000. Mrs. Griggs, on the death of her sister, a short time ago, had an addition to her fortune; she set up her coach, and went out almost every day airing, but suffered no male servant to sleep in her house. Her maids being tired frequently of their attendance on such a numerous household, she was induced at last to take a black woman to attend and feed them. This black woman had lived servant to Mrs. Griggs many years, and had a handsome annuity given her to take care of the cats.

The Capper farm had disappeared beneath University College. The sisters’ farmhouse still stood on the east side of Tottenham Court Road, but the land around it was becoming rapidly built up. In 1808, on a small patch of some open ground nearby, Richard Trevithick installed London’s first passenger railway as an advertisement for his locomotive. The ‘Catch Me Who Can’ was situated close to where Euston Station is today, and ran on a circular track, with journeys costing a shilling a ride. It was meant to prove that trains were faster than horses but Trevithick hadn’t laid his tracks well enough, and no one really saw how railways could take off. Ten years later, in 1818, John Harris Heal, a mattress-maker from the West Country, moved into what would become 196 Tottenham Court Road. He took over the old Capper farmhouse as a store and it survived until 1917, when it was demolished. Heal’s still sits on the same site.

In only a few decades, Bloomsbury went from farmland to a fashionable neighbourhood, exemplified by the elegant Bloomsbury Square. Large-scale developments by James Burton and Thomas Cubitt make up vast swathes of Bloomsbury, and on Great Russell Street, just opposite the British Museum, is the small terrace which represents John Nash’s first foray into domestic architecture. Burton and Nash would go on to be hugely influential in the West End of London with the Regent Street development, whilst Cubitt would develop Pimlico and Belgravia in a very different style. The most

important Georgian survival in Bloomsbury is Bedford Square, which was built upon the Cappers’ cow yard, and for which no architect is known.

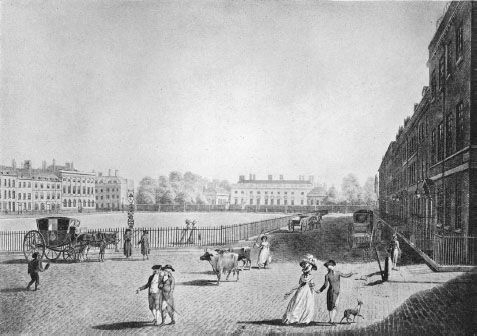

‘In Bloomsbury Square’, engraving by R. Pollard and F. Jukes, 1787

Relatively close by, to the west of Holborn, was the theatre neighbourhood of Covent Garden, with all its rackety allure. Francis Russell, the 4th Earl of Bedford, had begun developing the estate in 1631, and building progressed remarkably quickly, finishing in 1637. Covent Garden was unusual in that it was self-contained as a community, with the focus on the piazza designed by Inigo Jones. Here sat St Paul’s Church with a small local prison and whipping post. In front of the church the first Punch and Judy show appeared in England, in 1662, when Pietro Gimonde brought his toy theatre to the square.

Bedford House sat on the north side of the Strand. The gardens stretched all the way up to the piazza, where they were hidden behind a high wall. Against this wall Covent Garden market started, in 1677, when Bedford granted a lease on a market, six days a week, to two local residents for the trading of ‘

all manner of Fruites

, Flowers, roots, and herbs whatsoever’. The piazza was undeniably beautiful,

and retained the feel of the older pre-Restoration age. The sewerage provisions were good, at least until the end of the eighteenth century, so whilst the accommodations might be old-fashioned, they were well ventilated and not uncivilized. Only the noise and the press of people afflicted the piazza of Covent Garden – but to theatre people, what did that matter?

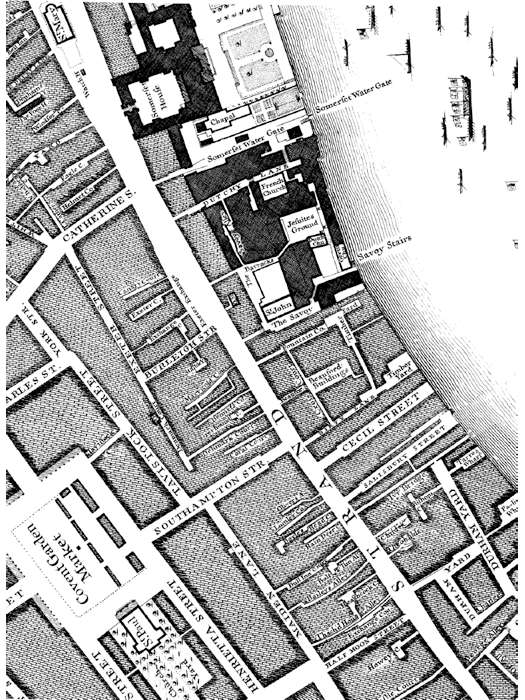

Covent Garden and the Strand, showing the Exeter Exchange and the area of the Savoy Palace, detail from John Rocque’s map, 1745

To the south was the Strand, the street connecting Westminster and the City. Roman in origin, its name originated during the Anglo-Saxon period and referred to the Old English word meaning ‘shore’, the road being close to the shallow banks of the Thames. In the Georgian period, the focal point of the Strand was the Exeter Exchange. It stood among taverns, eating houses and milk cellars where cows were led underground and milked for a fortnight before being sent back to local pastures. Between the Strand and the river were a maze of subdivided medieval palaces with slum-like infilling. Numerous steps and narrow sets of stairs led down to the river, where the water slopped and slapped loudly at high tide. Even when William Chambers and the Adam brothers built their fine developments – Somerset House and the Adelphi – the tunnels beneath the Adelphi complex, which were meant to serve the river, almost immediately became the haunt of London’s hookers and homeless. In amongst these narrow infested streets and courts were the most prominent areas of London’s second-hand book trade, together with the sale of pornography. Holywell Street, in particular, became famous for it, with over fifty pornography shops there in 1837.

It was a bustling, vibrant area of London. But from respectable Bloomsbury, in the north, to the rough thoroughfare of the Strand, there was an underlying theme. Bloomsbury housed the illegitimate offspring of prostitutes and indiscreet girls. Covent Garden was filled with actresses trading on their looks and charm, as did the area’s high proportion of female businesswomen in their shops and market stalls. The Strand was the home of London’s street prostitutes plying their wares, and just to the south were the pornographers operating from shops and stalls manned and frequented by both men and women. The theme, of course, was that sex sells.

In 1722, Thomas Coram was fifty-four and had led a hard life at sea. On his return to London, he went to work in the City but chose to live in Rotherhithe, ‘

the common Residence of Seafaring People’. Naturally inclined to hard work, he walked to and from the City at dawn and dusk, and was shocked to see so many ‘young Children exposed, sometimes alive, sometimes dead, and sometimes dying

’.

Many of these children were the offspring of street prostitutes who had died, become too sick or too drunk to care for them, or who had simply abandoned them in the street. Coram, a foundling himself, was not a wealthy man and decided to start a charity based on the joint-stock company model: the institution would operate as a legal

business, taking care of the children by bringing in donations which would then be overseen by a proper board. But people were still smarting from huge losses after the South Sea Bubble fiasco, and donations were hard to come by. Coram was undeterred and scored his first coup by signing up the Duchess of Somerset as a patron, in 1729. Over the following six years, he managed to convince seven more duchesses, eight countesses and five baronesses to pledge their support. The ‘Ladies Petition’ was key to the success of the project, linking charity with fashion in the way which would do so much good during this century.