Ghost Sea: A Novel (Dugger/Nello Series) (12 page)

Read Ghost Sea: A Novel (Dugger/Nello Series) Online

Authors: Ferenc Máté

A

COLD DAWN

drenched the ketch with dew. It beaded like rain on the varnish and ran in streaks down the paint. The sea was broken by loaf-shaped islands to the west and great mountains to the east, under whose vast, steep, wooded slopes long fjords twisted and vanished in the continent.

There were sounds in the galley and the smell of bacon frying. Then Charlie’s little face poked out the hatch—half fearful, half smiling—and he handed us steaming cups of coffee.

“You a helluva good Charlie, Charlie,” Nello said. “If we live through this, I give you nice big tip.”

Hay poked his head out and bade us good morning, but glanced furtively at us: that, if I remember right, was the last time he looked us in the eye until the end. He asked if we’d seen anything, looked around, saw nothing to catch his interest, and went below to eat his breakfast in the warmth.

Sea fog drifted over the cold water. The tide had turned but was neap during the day and with the waters here more open and the land breeze still coming down the fjords, we sailed north at three knots toward a lump of land that seemed to block our way.

“The pass,” Nello said, his voice flat from concern. “That’s where the North begins. It runs at thirteen knots; not the fastest pass on the coast, but the bloody longest. A two-mile dogleg of reefs and rocks. There’s only a half hour of slack water but with this engine it’ll take us an hour, if not more. The whirlpools will be up; and the overfalls. It flows at thirteen knots, Cappy, except it doesn’t flow—it boils. This whole fjord, fifty miles long and a mile wide, has to blow through a hundred-foot-wide throat in just six hours.

“Imagine a giant wave out at sea—what would it take for a wave to move at thirteen knots? Would have to be thirty feet high, right? Now imagine that wave blasting through those narrows. One colossal wave breaking and breaking, for hours. They call this end Yuculta Rapids, the far end Devil’s Hole.

“It’ll be good for you, Cappy. Take your mind off things.”

W

E WERE LESS

than two miles from the entrance of the pass—we could see the cleft between the steep bluffs where it began. But slack water was not for three more hours, so Nello steered us into the only anchorage around, a sandy hook-shaped cove, huddled below the dark wall of forest. A mass of brambles framed the cove: salal, blackberry, salmonberry, some fruit trees gone wild, all entwined into a green chaos. Someone had once eked out a life here.

With our slow sail during the night, we had given up hope of catching the Kwakiutl before the rapids; even paddling alone, he would have made it through, if not on the midnight then for sure on the dawn slack.

We dropped anchor and launched the skiff. We had Charlie bring a bucket and an old knife. “Good clams, Charlie,” Nello said, pushing off. “Good clams in the sand and oysters on the rocky point.” Hay was given the hatchet to cut some firewood, Nello took the Winchester, and I took my pistol.

Hay had been silent all morning. His manner had changed from that quiet arrogance to almost deferential; he seemed more like a hostage than the one who paid for the show. It took him a while to understand that we were going ashore just to stretch our legs, and he had to be told twice about the narrows and the slack. As we rowed, he kept turning back and looking north toward the pass.

I jumped ashore. It was good to stand on land for the first time in days.

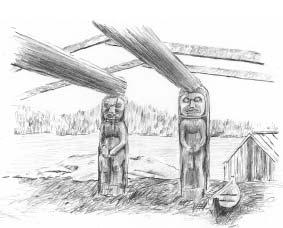

The sun rose behind a mountain and seemed to torch the trees, leaving only dark skeletons against the sky. The clamshell beach glowed white. Beyond the high-water mark, where shells were packed in dense welts by the storms, the shadow of the mountain still left the forest and brambles dark. An old log sticking out of the brambles into the sun, covered in lichen, seemed a comfortable place to rest. But as I sat, it collapsed under me; I fell into its hollow. It was a rotted, upside-down dugout canoe, the once-thick cedar sides as crumbly as a biscuit. I reached down behind me to push myself out but stopped; I felt as if I had stuck my fingers through some bars. I edged to one side to look down. The sun shone into the hole, onto my hand, and onto the rib cage which my fingers were gripping. Beside it, askew, as if looking up in curiosity, was the skull. Gap-toothed. The rest of him—shin-bones, shoulders, arms, all jumbled—had been scattered by animals and restacked by the tides. I backed away. I could discern odd shapes up in the salal now, mounds that had been houses, and more rotten “logs” just below a low bank of a midden. I walked along the brambles searching in the shadows and saw a drooping eye look back; a burial pole lay face-up just beyond the sand. At the end of the midden was the solitary remnant of a house: a carved post with a once-ferocious wolf’s head, teeth bared, half rotted away. A fern, waving in the light breeze, sprouted from one ear. Inland of the brambles, in a great cedar whose lower branches had been desiccated by time, a half dozen boxes hung or were wedged in the crooks. Parts of them had rotted and fallen long ago, and out hung shreds of blankets, clothes, feathers, and more bones. A raven had made a nest in one of them; it now flew off cawing lowly over the cove.

“Leqwildex,” Nello said beside me. “A rich village. They fished the rapids. Two hundred people lived here when the smallpox hit that spring during the eulachon run. There were nineteen left alive when the salmon came in July. Most were old—moved away, why stay? The village was dead.”

Charlie was down on the water’s edge, singing a little song, digging with a stick into the mounds of mud that squirted, then digging with his hands and clanging the clams loudly into the bucket.

Nello went and pried some oysters off a tidal rock. I made a fire with driftwood, and threw the oysters right onto the coals. “Come on, Charlie,” Nello called, and he cut a long switch with a forked end, went to the water’s edge, kicked off his boots, rolled up his pants and waded in. Charlie did the same. They stood in the water with Nello poised like some great heron, switch in hand, its fork below the surface. Then he lunged, stopped, and with a slow, smooth movement lifted the switch with a big rock crab, too dumb to let go, hanging from it. He laid it on the shore on its back. The crab’s legs and claws sawed the air, and I drove the sharp edge of a rock right through his pale belly—an ugly crunching sound. The legs went limp. Grabbing both sets of claws and legs, I tore them from the shell. There was nothing left but a hollow. I stripped the spongy tissue from the legs, rinsed them in the sea, then threw them on the coals.

We sat under a cherry tree gone wild and leaning precariously seaward from the midden. We ate without a word. Nello threw the shells, clattering, on the rocks.

“They say that was the best eulachon run ever.”

HAT

S

PRING

T

he ravages of that most frightful disease continue unabated. The northern tribes are now nearly exterminated. They have disappeared from the face of this fair earth, at the approach of the paleface, as snow melts beneath the rays of the noonday sun.

Captain Shaff of the schooner

Nonpareil

informs us that the Indians recently sent back North are dying fast. Out of 100, about 15 remain alive.

The small pox seems to have exhausted itself, for want of material to work upon.

—F

ROM THE PAGES OF

The British Colonist

“I

had just turned five,” Nello began, “when it hit our village.

“My mother got sick; she started to go blind. My grandfather paid the captain of an old steamer that hauled boom chain and steel cable to logging camps to take her down to the hospital in Victoria. He sent me with her to get away from the sickness. He had been chief of our

na’mima

, but got old and passed down the title to my elder brother, who fell through the ice the next winter and died. My grandfather had a great bird burial pole carved for him; its beak alone was longer than me. Cost him every penny he had, so with no money to pay for our passage, he offered the captain of the steamer all he had left: the pole. He had offered himself as a slave but the captain told him nicely that he didn’t need one and he preferred the pole to sell to collectors in Victoria. My grandfather sat beside the pole with a lost look in his eyes and watched two sailors hack at it with hatchets.

“It was the most splendid burial pole in the islands, painted all bright colors, even the sick had dragged themselves outside to watch when it went up; now they dragged themselves out to watch it get hacked down. Those sailors were no loggers, didn’t know a damn about how to fell a tree, so they never bothered to back cut, just hacked away stupidly at its front, cursing and laughing all the while. The villagers sat silent. The sailors got angry as they went on, hacked harder, cursed louder, until finally the pole made a sound of pain—leaned toward the sea, turned slightly, then splintered. To my child’s eye, it seemed for a moment that the great bird took flight—flew miraculously over the sea, over the islands, its reds and yellows defiant in the mist—but then it just fell, in a quick sad arc, beak-first into the sand. Only a giant splinter remained standing. The steamer backed close to the beach, churning up the silt of the shallows. They threw a towline around the bird, then the funnel belched soot, and it surged ahead. Some of the village men began beating a slow rhythm on a board.

“The rope shuddered so tight that beads of water flew from it; then, with an ugly crunch that hurt my heart so much I still recall the pain, its beak cracked at its base and it lunged forward through the water. The beating on the board grew frantic. Women wailed. My poor grandfather stood unmoving, his head down, staring at the gash the bird left in the sand.

“Out in the bay, the steamer dropped anchor. The drumming on the board grew irregular and it began to rain, a soft drizzle. My grandfather hadn’t moved; just stood and stared. He was still there as, man by man, the drummers fell silent. Night came. A bonfire was lit on the beach, in the rain, near the little house on stilts where the sick people stayed to be near the curing power of killer whales and the sea. My grandfather came and sat on a rusted sewing machine that someone had long ago bartered for a dugout war canoe.

“In the morning, they carried my mother down. My aunt held my hand as we followed; she told me not to be afraid because the raven would look after me, and to be strong like the Hamatsa and hard like our warriors. Meanwhile, she held my hand so tight she almost crushed my fingers. How could I be strong with all my fingers broken? I was watching them load my mother into a canoe in the rain. We were well away from the shore but still I could hear my aunt shouting advice. Bless her heart.

“They put us under the tarp that stretched from the deckhouse to the backstay of the riding sail, but the wind and the boat’s rolling sent the rain in under it. We didn’t mind; we’re a people used to rain. The rain is our world. We suffer when the sun comes out and blinds us with the sparkling sea.

“The engine throbbed as the anchor chain came in. My mother’s eyes smiled up at me but her face was still. By then the smallpox had made her almost blind but she tried to pretend that she still saw me as before. There was a sour smoke from the coal fire in the boiler. We moved ahead and the great bird rolled, went down, then leapt like a fish trying to throw a hook. Our village vanished in the mist. I heard a long wail, soft like the rain.

“At the bottom of our passage we didn’t turn west toward the strait like I thought we would—I could see the clouds above it racing north, whipped to a wedge by the wind—instead we turned east, into the islands. I heard the mate argue with the captain. The mate said to try the strait, for the love of God, but the captain yelled back that he wasn’t going where the wind could blow you off the deck, and the waves were so goddamn steep they fell on you like a wall. What would be the use anyway: the squaw would surely die. The mate told him not to bullshit about the squaw, that all he really cared about was not losing his blessed pole. I kept wondering what a ‘squaw’ was. The captain ruled—we weaved east and south among the islands. In the canoe passage the tide was so low the bird’s beak kept hitting bottom.

“My mother lay quietly. I poured some water between her lips and pushed a morsel of dried salmon past her teeth. She chewed out of obligation. The storm started to break over the strait and shafts of sunlight shot down from the clouds. I liked that boat—I can’t remember why—maybe I thought it would make my mother well again.

“W

E BUCKED THE TIDE

. It took us until afternoon to catch sight of Broken Islands, and beyond them the clouds racing up the strait. We swung near Hope Village. I could see the beach, the midden, the houses, all deserted; no smoke, no people. The canoes were there, all right, pulled high on the beach, black against the white of the clam shell, but there was no one—not even the old or sick, who normally stay behind when the rest of the village moves to summer fishing grounds. Anyway, it was too early for the salmon run and the eulachons had gone. Besides, the roof planks and the wall planks were all there—like the canoes.

“We headed west.

“I was looking forward to going down the strait, especially in the blow. Children have no fear, not even when their little world is ending. Maybe they just don’t know that word, the ‘end.’ Anyway, I was hoping for a blow. Hell, I had been out there before; just me and my uncle, he was of the Killer Whale Clan. He loved killer whales. They would come into the strait in the summer, favored a bight on the big island, where the Nimpkish River brought the best morsels to the sea and attracted salmon. But my uncle didn’t go to fish; he went to pray.

“He and I would paddle out to the bight just before slack tide and we would sit there, tearing smoked clams with our teeth off the yew skewers—goddamn clams harder than your boot sole—and my uncle would sit like a rock staring down at the water as if that would somehow make the killer whales sound. The air around the whirlpools smelled of the bottom of the sea.

“Sometimes he would stand up and chant; at others he’d have a pee over the side. I was never sure which it was that brought up the whales, but my God, when they came! Always from the north. Always from the north. A small female led the herd—she used to sound with a quick fling of her head—then three or four young males side by side, some more females, and at the end the ‘old man,’ my uncle called him, with his tall fin split from battle. He would sound and hang in the air an improbably long time, shedding sheets of water, his big black body and white cheeks aglow in the sun, the smell of the spray he shot filling the air with stink, and my uncle there with his arms open wide, beaming with pride as if he had, by magic, conjured them from the deep. Maybe he did. I wouldn’t bet against it even now.

“So he’d stand chanting, and he’d never notice the wakes from the whales coming at us, always on our beam as we drifted in the stream, and when they hit, he’d be taken by surprise, lose his balance, and as often as not fall into the sea.

“The whales came every time, always together. They stick together all their lives; like us Injuns. Not like us whites.

“T

HE CAPTAIN KEPT

his steamer near the shore where the wind was calmer, but still we came down the strait bouncing, the bird bobbing. At the fork, instead of going on straight south to Victoria, he swung east up a sound toward the snowy mountains. We slowed, and the big bird banged the stern, and the captain came out and asked nicely how my mother was. By then she was so blind she didn’t even blink when I leaned down to her. Her skin began to slough away.

“The captain said we could make better time if he went up the sound and left the bird with a friend on a homestead, then we could barrel on full speed to Victoria. But with the wind funneling up the sound, it was even rougher than the strait, so he would leave my mother and me for an hour on a sheltered little island. They rowed us ashore with some salmon and water and two blankets. Said she would eat better on firm ground. They put her in the lee of the salal, then steamed away, full speed, up the sound.

“We never saw them again.

“I covered her with the blankets, then cut some hemlock branches with an oyster shell and built a lean-to over her. I poured more water on her lips, but most of it ran down her face. I can’t remember how many days we stayed there. The sun was often out but the nights were cold.

“It was a beautiful sunny morning when she died. There was a mist over the sea, and the water was so flat, you couldn’t tell where it ended and the shore began. The sun was on her face. I could tell she liked it. She sort of smiled. And it stayed. That smile. After a while, I put a raven feather under her nose like I’d seen my brother do with shot bear, but the feather didn’t move. I held it for a long time.

“The next morning some crows came, so I began to bury her like our people do at the summer grounds where the shore is all rock. I built a house gently over her. Rocks, driftwood, bark, and lots of shells to make it pretty.

“I can’t recall how many days passed before the church boat came down the sound and saw me standing on the shore. At first I didn’t want to go. Didn’t want to leave my mother. They took me to Victoria, to a mission. Full of Indian kids with no parents. My father came at Christmas and took me to my

nonna

and

nonno

, near Pisa.

“They say there were eight thousand of us Kwakiutl that spring, but barely nine hundred left by the fall.”