gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (44 page)

Although Kharsag, like the Duku mound, is sometimes described as the Mountain of the East,

8

an allusion to the direction of the rising sun, it is also occasionally situated in the north,

9

the direction of the Eastern Taurus Mountains and the Armenian Highlands. So where exactly was Kharsag, if indeed it was a physical location?

THE NIPPUR FOUNDATION CYLINDER

One Sumero-Akkadian inscription, dating to around 2600 BC and found on a terra-cotta cylinder deposited in the foundations of the “Mountain House” (E-kur) of the god Enlil in the city of Nippur in southern Iraq, speaks of Kharsag in direct association with the Tigris and Euphrates rivers:

The holy Tigris, the holy Euphrates,

The holy scepter of Enlil

Establish Kharsag;

They give abundance.

His scepter protects (?);

[to] its lord, a prayer . .

.

the sprouts of the land.

10

Unless this is a reference to the

mouths

of the Tigris and Euphrates, it implies that the two great rivers were seen to sprout forth from Kharsag, the Mountain of the World. That Kharsag might be an actual mountain to the north or northeast of Mesopotamia has long been realized, although most usually it is identified with Mount Ararat,

11

a sacred mountain in eastern Turkey of paramount importance to Christian tradition.

It was here, we are told, that Noah’s ark came to rest after the Great Flood, although this, as we shall see, is a complete misnomer. The original Genesis account says only that the ark came to rest “on [the] mountains of Ararat (Gen. 8:4),” a reference to the kingdom of Ararat. This is the Hebrew name for Urartu, which appears in Assyrian and Babylonian literature for the first time around the thirteenth century BC. At its height Urartu stretched from the Eastern Taurus Mountains in the south all the way to the Caucasus Mountains in the north, with its main heartland being in the region of the Armenian Highlands and Lake Van. Never does the Bible allude directly to Mount Ararat. Yet this has not stopped overzealous clergy members, theologians, and scholars identifying the so-called Place of Descent, where Noah’s ark made landfall, with the tallest mountain in Armenia, which is Mount Massis, popularly known today as Mount Ararat.

MOUNT AL-JUDI

Mount Massis is unquestionably a mountain very sacred in Armenian tradition, and evidence of human activity here goes back to prehistoric times. Yet nothing before the fifth century AD associates it with the story of Noah’s ark. Indeed, the inhabitants of the region point out another mountain as the true Place of Descent. This is Mount al-Judi, the modern Cudi Dağ, close to the Turkish-Syrian border. At the foot of the mountain is the town of Cizre, which tradition asserts is the site of Thamanin, the settlement established by Noah and his family after leaving the ark.

Mount al-Judi is the Place of Descent recognized by Babylonian Jews, Christians of the Assyrian Church, Muslims (as stated in the Holy Qur’an’s Sura 11:44), Yezidis (a Kurdish angel-worshipping religion), and “Chaldeans,”

12

a reference to the peoples of Northern Mesopotamia. This same mountain is asserted to be the landing place of Noah’s ark by Berossus (a Babylonian historian, ca. 250 BC) and Abydenus (a Greek historian, ca. 200 BC), who stated that inhabitants thereabouts “scraped the pitch off the planks as a rarity, and carried it about them for an amulet,” while “the wood of the vessel (was used) against many diseases with wonderful success.”

13

According to English Orientalist George Sale (1697–1736), who made an English translation of the Holy Qur’an published in 1734, relics of the ark were “seen here in the time of Epiphanius [a famous church leader who lived at the end of fourth century AD], if we may believe him; and we are told the [Byzantine] emperor Heraclius [who ruled AD 610–641] went from the town of Thamanin up to the mountain al Jûdi, and saw the place of the ark.”

14

Sale mentions also that there was once an ancient monastery on the summit of Mount al-Judi, which was destroyed by lightning in AD 776. After this time, belief that the mountain was the Place of Descent declined, its place taken by Mount Massis, called by the Turks Agri Dağ and by the Christians Mount Ararat.

15

THE SWITCH TO MOUNT MASSIS

The Armenian Church was directly responsible for transferring the Place of Descent from Mount al-Judi to the more northerly Mount Massis,

16

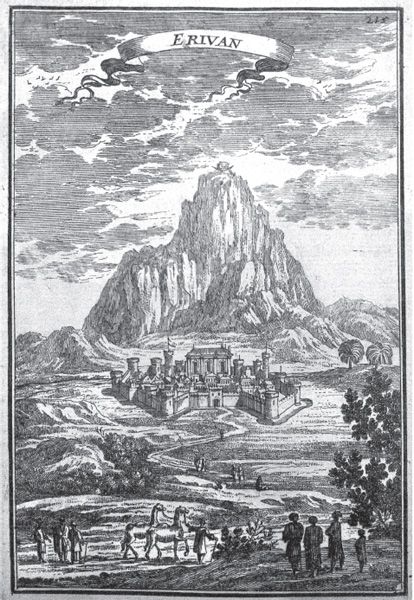

a holy mountain under the jurisdiction of the Mother See of Holy Echmiadzin, a church and monastery located in Vagharshapat, near the city of Erivan, or Yerevan, the capital of the Republic of Armenia (see figure 30.1). As the seat of the Catholicos, or head of the Armenian Church, Holy Echmiadzin is to the Armenians what the Vatican is to the Catholic Church. When viewed from Echmiadzin, Mount Massis seems to rise up from the surrounding plain to dominate the southern skyline.

The change in location of the Place of Descent from Mount al-Judi to Mount Massis was almost certainly political and occurred following the ruling of the Council of Ephesus in 431, which banned the ancient Assyrian Church from the Orthodox Catholic Church because of its unorthodox views on Christ’s dualist nature. At the time Mount al-Judi was under the jurisdiction of the Assyrian Church, the Armenian Church’s southern rival, so a switch of interest away from Mount al-Judi to Mount Massis was deemed appropriate, as the Armenians did not want the Assyrians to have control of this important place of pilgrimage.

Yet before this time the Armenian Church was, seemingly, happy to accept Mount al-Judi as the site of the Place of Descent. This is brought out in an Armenian chronicle known as the

Epic Histories,

attributed to an Armenian historian named Faustus of Byzantium, who lived in the fifth century. The book chronicles the visit of Jacob (or James), the second bishop of Nisibis in Northern Mesopotamia, to Mount al-Judi. Here the “Armenian saint,” who was born at the end of the third century, is said to have found the “wood of Noah’s Ark.”

17

Today, only Christians believe that Mount Ararat is the site where Noah’s ark came to rest. Yet the sheer potency of this belief remains so strong that it has inspired a number of high-profile attempts to locate the remains of the ark on the slopes of Mount Ararat. All of these expeditions have either come to nothing or resulted in clandestine video footage of the alleged remains of a petrified boat, which becomes impossible to verify.

The reason for diverting from the main theme of the chapter to cite these facts is that the Christian belief in the power of Mount Ararat has over the past three hundred years seriously clouded scholarly judgment regarding the geographical placement of legendary locations connected with either Northern Mesopotamia or the Armenian Highlands. For instance, it was almost certainly the Christian obsession with Mount Ararat that led to its being identified with Kharsag.

18

Yet no major rivers take their rise there, especially not the Tigris and Euphrates mentioned in the inscription recorded on the Nippur foundation cylinder.

Since it was anciently believed that the Tigris and Euphrates stemmed from the same source, it is more likely that Kharsag should be identified with the Bingöl massif, which is located around 150 miles (240 kilometers) west-southwest of Mount Ararat. Just as the Armenians saw Bingöl Mountain as the Place of the Gods, the Sumero-Akkadians saw Kharsag as “where the gods were born”

19

or “where the gods had their seat,”

20

an allusion to the presence thereabouts of the Duku mound, which, as we have seen, was very likely envisaged as a tell, an abandoned occupational mound, dating back to the age of the gods.

Figure 30.1. Old print of Mount Ararat as seen from Erivan, modern Yerevan, the Republic of Armenia’s capital and largest city.

Interestingly, some accounts of the Duku mound speak of something called the Ancient City,

21

which was believed to have been built right on top of it, underneath which was the Abzu.

22

Although scholars consider that this account relates to the ancient city of Eridu, which was under the patronage of Enki and had its own representation of both the Duku mound and Abzu, chances are that the concept of the Ancient City relates to a built structure existing on the original Duku—one that was seen to sink down into the hill when its ancestor gods withdrew into the mound.

THE NIPPUR FOUNDATION CYLINDER

In the 1980s British historical writer and geologist Christian O’Brien (1914–2001) made a careful study of the Nippur foundation cylinder (correctly entitled the Barton Cylinder, after George A. Barton [1859–1942], the Canadian clergyman and professor of Semitic languages who first translated its text). He concluded that its inscription alluded to some kind of settlement of the Anunnaki existing in Kharsag, which he interpreted as meaning “principal fenced enclosure” or “lofty fenced enclosure.”

23

It was a conviction reinforced by the fact that the Akkadian word

edin,

meaning “plain,” “plateau,” or “steppe,” is twice used in connection with this highland “settlement.”

24

Was this the “Ancient City” existing on top of the Duku mound?

Among the Anunnaki named in the Nippur foundation cylinder is the great lord Enlil, along with Enki, whom we have already met; Utu, or Ugmash, the sun god; Anu, whose name means “heaven”; and Enlil’s (usually Enki’s) consort, Ninkharsag, a name that translates as “Lady of the Sacred Mountain.” Significantly, she appears also under the Akkadian name Šir (the equivalent of the Sumerian Muš, pronounced

mush

),

25

meaning “Serpent,” and is given the epithet Bê-lit, meaning “Divine Lady.”

26

Even though Mesopotamian scholar George A. Barton assumed that Šir was a “serpent goddess” venerated in the city of Nippur,

27

O’Brien interpreted her name as meaning “Serpent Lady”

28

and identified her as one of the Anunnaki living in Kharsag.

CULT OF THE SNAKE

It is curious that Ninkharsag, also called Šir (or Muš), the wife of Enlil or Enki, is seen as one of the Anunnaki living at Kharsag, for a cult of the snake is known to have thrived on the plain of Mush (which in Turkish is written Muş). A medieval translation of a work by the fourth-century Armenian abbot Zenob Glak says that snake worship was introduced to the kingdom of Taron, the ancient name of Mush, by “Hindoos,” who arrived from the east in 149 BC.

29

They built cities and temples here that were destroyed by Gregory the Illuminator during his crusade against the pagans at the beginning of the fourth century AD. Apparently, the temples were located at Ashtishat, close to the road between Mush and Bingöl Mountain, where afterward Surb Karapet, the Monastery of Saint John the Baptist, was built.

This story suggests that Mush derives its name from the Sumerian Muš, the Akkadian Šir (pronounced

shir

), both meaning “snake” (even though in Armenian popular tradition Mush, as the word

mshush,

means “fog,” a name deriving from a story in which the Armenian goddess Anahita raised a mist so that her daughter Astghik, goddess of love and beauty, could bathe without any mortal setting eyes on her nakedness). If so, then the ancient snake cult known to have existed at Ashtishat (the principal seat of the goddess Astghik, whose symbol was the

vishap,

a word meaning “snake” or “dragon”) probably predates the arrival of the “Hindoos” and most likely relates to a time when the region was under the control of one of the Mesopotamian civilizations. If so, then this has profound implications for the identification of Kharsag with Bingöl Mountain, and the Garden of Eden with the Mush Plain, for in his book

The Genius of the Few,

Christian O’Brien argues that the account of Kharsag preserved in the Nippur foundation cylinder was perhaps the origin of the Genesis account of the terrestrial Paradise:

The parallels between this epic account and the Hebraic record at the Garden of Eden are highly convincing. Not only is “Eden” twice mentioned, but the reference to the “Serpent Lady”, as an epithet for Ninkharsag . . . [is] clear confirmation of the scientific nature of the work carried out by the equivalent Serpents in the Hebrew account.

30