gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (20 page)

If the Hooded Ones did exist, then what might have been their powerful message, and where did they come from? To even start to answer these questions we need to return to the strange symbolism of the T-shaped pillars, in particular those that stand proud in the center of Enclosure D, arguably the most accomplished structure uncovered so far.

12

THE FOX’S TAIL

T

he imposing central pillars in Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosure D both sport wide belts, at the front of which, beneath a centrally placed belt buckle, fox-pelt loincloths have been carved, the animal’s hind legs and long, bushy tail extending down to knee level (see

plate 13

). Further emphasizing the eastern monolith’s vulpine character is the presence on its inner face of a leaping fox, something present also on the central pillars of Enclosures B, the eastern central pillar in Enclosure A, and the western central pillar in Enclosure C.

These images of the fox, along with the high level of faunal remains belonging to the red fox (

Vulpes vulpes

) found at Göbekli Tepe, led archaeozoologist Joris Peters, writing with Klaus Schmidt, to conclude that the interest in this canine creature went beyond any domestic usage and was connected in some way with the “exploitation of its pelt and/or the utilization of fox teeth for ornamental purposes.”

1

That this statement was made even

before

the discovery of the fox-pelt loincloths carved on the front narrow faces of Enclosure D’s central pillars means that what Peters and Schmidt go on to say in the same paper should not be ignored, for in their opinion “a specific worship of foxes may be reflected here.”

2

That leaping foxes appear also on the central pillars in the large enclosures at Göbekli Tepe suggests that the entrant passing between them would have encountered this vulpine creature upon accessing the otherworldly environment reached through the enclosures’ inner recesses. So why foxes, especially as they are usually seen in indigenous mythologies as cosmic tricksters, evil twins of the true creator god, responsible only for chaos and disarray in the universe?

BELT BUCKLE CLUE

Was the fox the chosen animal totem of the Hooded Ones, the faceless individuals portrayed by the T-shaped pillars? If the answer is yes, then what does it mean? The key is the strange belt buckle immediately above the fox-pelt loincloth on the enclosure’s eastern pillar (Pillar 18). A similar belt buckle is seen on the western pillar (Pillar 31), although here it is left unadorned, in the same way that the figure’s belt, in complete contrast to the one worn by its eastern counterpart, is completely devoid of any glyphs or ideograms.

Only on the eastern pillar does the belt buckle reveal something very significant indeed. It shows a glyph composed of a thick letter U that cups within its concave form a large circle from which emerge three prongs that stand upward (see figure 12.1 and

plate 13

). That this emblem is worn centrally, on a belt festooned with strange ideograms, suggests that it has a very specific function. If so, then what might this have been?

THREE-TAILED COMET

Having examined the belt buckle glyph at some length, it is the author’s opinion that it represents the principal components of a comet. The circle is its head, or nucleus, and the U-shape is the bow shock that bends around the leading edge of the nucleus and trails away as the halo. The upright prongs denote three separate tails, with multiple tails being a common feature of comets (see figure 12.2).

That the comet’s “tails” on the belt buckle stand upward also makes sense, for these are often seen to trail into the night sky as the comet reaches perihelion. This is its final approach and slingshot orbit around the sun. As this takes place the solar magnetic fields cause the gaseous particles of the comet to point away from the sun, so when the comet is seen in the sky, either in the predawn light (before perihelion) or, alternatively, just after sunset (following perihelion), its tail or tails point upward from the horizon, creating an unforgettable sight (see figure 12.3).

Figure 12.1. The belt on Enclosure D’s eastern central pillar (Pillar 18) showing its belt buckle device and fox-pelt loincloth.

Figure 12.2. Left, comet showing the bow shock around its leading edge and, right, Halley’s Comet in 1910. Both resemble elements of Pillar 18’s belt buckle.

Figure 12.3. The Great Comet of 1861 showing its triple tail.

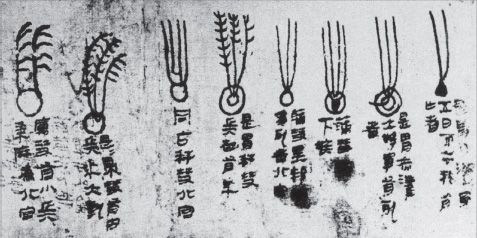

The idea that the belt buckle glyph shows a comet is strengthened by its similarity to three-tailed comets seen in an ancient Chinese silk text. The Mawangdui cometary atlas (also known as the

Book of Silk

), created ca. 300–200 BC and named after the Han Dynasty mound tomb in which it was discovered in the 1970s, lists, in all, twenty-nine different cometary forms and the disasters associated with them. In figure 12.4, we see that in more than one example there is a striking resemblance to the Göbekli Tepe belt buckle design, especially as the comets are drawn with their tails pointing upward.

3

MARK OF THE COMET

Yet even assuming that the belt buckle glyph

does

show a comet, could this not simply be a personal device without any connection to the function of Göbekli Tepe? This appears unlikely, as the pillar is festooned with ideograms of a probable celestial nature. The belt’s C and H glyphs would appear to have cosmological values, as does the carved eye held within a slim crescent worn around the “neck” of the T-shaped monolith. In addition to this, it does seem as if Enclosure D’s eastern central pillar has a greater function than its western neighbor, almost as if one twin is alive, while the other functions as a ghost or echo of the other.

Figure 12.4. The Chinese Mawangdui atlas (or Book of Silk) from ca. 300– 200 BC, showing the entry for the various different types of comet, some resembling the belt buckle on Göbekli Tepe’s pillar.

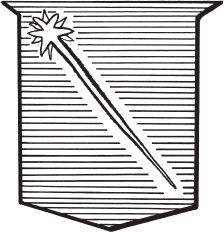

Regardless of these facts Pillar 18’s belt buckle is simply not enough to demonstrate that comets held some special importance at Göbekli Tepe. There is, however, another tantalizing link between the symbol of the comet and Enclosure D—this being the fox-pelt loincloths seen beneath the belt buckle on both monoliths. Universally the fox,

and the fox tail in particular,

has been seen as a metaphor for comets, due to the hairlike appearance of their long tails. Even in British heraldry the device known as the comet or blazing star is drawn to resemble the fox’s tail (see figure 12.5 on p. 124). It is for this reason that comets have occasionally been personified as having clear vulpine and—as we shall see—canine (doglike) and lupine (wolflike) qualities of a dark, foreboding nature.

COMETARY CANINES

Chinese myths and legends, for instance, speak of mountain demons called

t’ ien-kou

(

tengu

in Japanese), “heavenly dogs.” Folk tradition asserts that these supernatural creatures derive their name from comets or meteors falling to earth, for it is said they resemble the tails of dogs or foxes. One account speaks of t’ien-kou as:

Figure 12.5. Medieval heraldic device known as the comet or blazing star with its distinctive “fox tail.”

a huge dog with a tail of fire like a comet. Its home was in the heavens, but it sustained itself by descending to earth every night and seeking out human children to eat. If it could not catch any children it would attack a human adult and consume his liver.

4

It is this dreaded fear of comets, seen in terms of malevolent supernatural creatures in canine form, that brings us to a fascinating account recorded by a Spanish Jesuit priest who journeyed through northern Mexico in 1607–1608. While staying in the town of Parras in the state of Coahuila, Andrés Pérez de Ribas (1576–1655) witnessed the priests of the local tribe, perhaps the Tlaxcalan Indians, conduct a powerful and somewhat macabre ceremony to ward off the baleful influence of a comet (almost certainly it was Halley’s Comet, which made an appearance in 1607). According to him:

The end of the comet (some of them said) was in the form of plumage: others said it had the form of an animal’s tail. For this reason some came with feathers on their heads, and others with a lion’s or fox’s tail, each of them mimicking the animal he represented. In the middle of the plaza there was a great bonfire into which they threw their baskets [containing dead animals] along with everything in them. They did this in order to burn up and sacrifice these things, so they would rise up as smoke to the comet. As a result, the comet would have some food during those days and would therefore do them no harm.

5

Although this strange ceremony to negate the influence of a comet took place on another continent nearly ten thousand years after the abandonment of Göbekli Tepe, the very specific use of fox (and lion) tails not just to represent the comet but also to connect with its supernatural nature, cannot be ignored. This form of sympathetic magic was the domain of the priest or shaman, and there can be little question that very similar ceremonies took place on other continents in past ages.