gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (23 page)

Figure 15.2. Biela’s comet in 1846, soon after it split in two.

THE MONSTROUS REGIMENT

The

Prose Edda

account reveals next how the monstrous regiment “direct their course to the battle-field called Vigrid. Thither repair also the Fenris-wolf and the Midgard-serpent, and Loki with all the followers of Hel, and Hrym with all the frost-giants.”

15

For Donnelly this implied that “all these evil forces, the comets, the fire, the devil, and death, have taken possession of the great plain, the heart of the civilized land. The scene is located in this spot, because probably it was from this spot the legends were afterward dispersed to all the world.”

16

This is an interesting statement since it supposes that somewhere in the ancient world there existed a heartland, a place where all these great tragedies were played out and witnessed by those who survived this tumultuous ordeal.

BATTLE OF LIGHT AND DARKNESS

It is after this time that the gods, as the defenders of the world, begin to fight back and start to win the day against the hellish terrors, although not without casualties on their own side. Heimdal, the guardian of Bifrost Bridge, blows the Gjallarhorn, which had been hidden beneath Yggdrasil. It awakens the gods, allowing the battle of Ragnarök to commence. The sky god Odin takes flight to Mimir’s Well, a sacred pool at the foot of Yggdrasil. Here lurks the head of his friend Mimir, which he asks to grant him advice. After that we are told the “ash Yggdrasil begins to quiver, nor is there anything in heaven or on earth that does not fear and tremble in that terrible hour.”

17

It is a hint once more that the world pillar is being shaken, tilted even, by the events transpiring both on the ground and in the air.

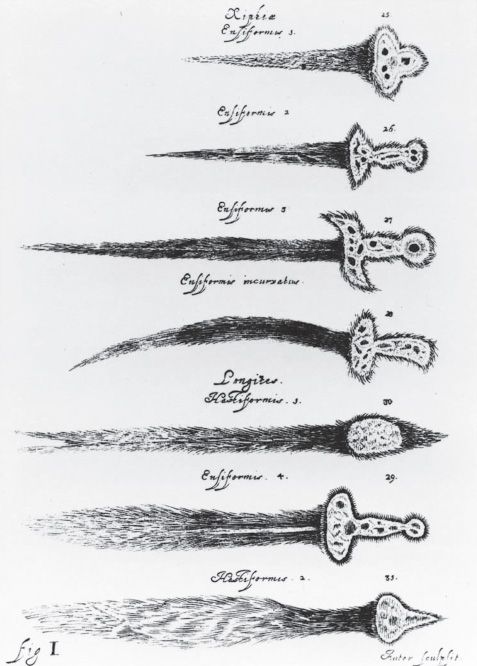

Figure 15.3. A page from Johannes Hevelius’s Cometographia of 1668 showing comets as daggers and swords.

Thereafter, the gods enter Vigrid and engage in battle: “That day the dog Garm, that had been chained in the Gnipa-cave, breaks loose. He is the most fearful monster of all, and attacks Tyr, and they kill each other.”

18

At the same time, the god Thor is able to slay the Midgard Serpent but dies as a consequence of the poisonous venom the monster breathes on him. Inevitably, Donnelly saw Garm, described as a bloodstained hound that guards “Hel’s gate,” as alluding to yet another comet fragment.

19

Its appearance marks the entry of a fourth canid into the Ragnarök story.

THE EARTH SINKS

At this point in the battle Odin takes on the Fenris Wolf but is swallowed by the monster, which he himself had helped to rear (is this “because Odin had a connection with wolves?” asks one commentator

20

). On seeing the death of his father, Odin’s son Víðarr rushes at the beast and, wearing a magic boot prepared specially for the confrontation, stamps his foot into the Fenris Wolf ’s mouth and holds open its lower jaw. He then uses brute force to pull up on the beast’s jaw, an action that brings about its instant demise (see figure 15.4).

Figure 15.4. Shaft of the Gosforth Cross in Cumbria, England, showing Odin’s son Víðarr killing the Fenris Wolf. Note its knotted serpentine tail.

The Fenris Wolf ’s father, Loki, comes up against the god Heimdal, and they kill each other, at which: “Surt flings fire and flame over the world. Smoke wreathes up around the all-nourishing tree (Yggdrasil), the high names play against the heavens, and earth consumed sinks down beneath the sea.”

21

Once more, this is a clear sign of some kind of global conflagration, as well as an all-encompassing deluge that begins to engulf the earth, making it appear as if it is sinking beneath the waves.

THE FIMBUL-WINTER

Just in these few lines we see telltale signs of the aftermath of a major cataclysm that is set to decimate the earth and everything upon it, a surmise affirmed by the fact that the

Prose Edda

speaks also of the world being plunged into an age of ice:

The growing depravity and strife in the world proclaim the approach of this great event. First there is a winter called Fimbul-winter, during which snow will fall from the four corners of the world; the frosts will be very severe, the winds piercing, the weather tempestuous, and the sun will impart no gladness. Three such winters shall pass away without being tempered.

22

Donnelly easily recognized these words as describing the onset of a glacial age, following the impact of the comets. This great freeze, which seems to come on quickly, does eventually begin to thaw, as the clouds of darkness disappear and a new sun and moon are born. The floods recede also, leading to a complete renewal of nature.

Thereafter emerge the sole human survivors:

During the conflagration caused by Surt’s fire, a woman by name Lif (life) and a man named Lifthraser lie concealed in Hodmimer’s forest. The dew of the dawn serves them for food, and so great a race shall spring from them that their descendants shall soon spread over the whole earth.”

23

Donnelly suggested that it was from a cave that Lif and Lifthraser emerged because caves feature worldwide in the regeneration of humankind in the wake of catastrophes, while the reference to them giving birth to a great “race” implies that, in Scandinavian tradition at least, the current human population derives from these two individuals. Others survive the cataclysm as well, including Víðarr and Vale, the sons of Odin, and Mode and Magne, the sons of Thor. Yet these are not mortal beings like Lif and Lifthraser. They are offspring of the Æsir, who are destined to dwell on the plains of Ida, where stands the world tree, Yggdrasil, alongside Mimir’s Well and Asgard, the home of the gods.

DONNELLY’S DATES

From what we read here, it does seem possible that the Eddas, like very similar myths and legends from around the world, contain echoes of a devastating catastrophe that engulfed the world during some distant epoch. Donnelly envisaged this sequence of events beginning around thirty thousand years ago, at the height of the last ice age, and culminating around eleven thousand to eight thousand years ago.

24

As we shall see, his later dates correspond pretty well with the proposed timescale of cosmic catastrophes now believed to have taken place globally toward the end of the last ice age, triggered by a major impact event around 10,900 BC (see chapter 17).

Donnelly was convinced that a comet, or indeed a series of comets, was responsible for these cataclysms, and once again he was bang on the money, as we shall see soon enough. His proposal that these global killers were portrayed in ancient myths and legends as supernatural creatures of the earth and sky also seems to be right, a theory advanced since that time by a number of different catastrophists, who have each put a unique spin on the subject.

NUCLEAR WINTER

In the Ragnarök account, various monsters are cited as being responsible for destruction in this world, including the Midgard Serpent, the fire giant Surt, and at least four canids, three of them wolves. Two of the wolves are accused of having swallowed the sun and moon, and this quite possibly describes the temporary disappearance of the heavenly bodies that would inevitably follow a catastrophe of this scale. A comet or asteroid impacting the earth would create unimaginable clouds of smoke, dust, and microparticles of various kinds that would be thrust into the upper atmosphere, creating what is known as a nuclear winter, a total blackout of available light. This debris, which would probably remain airborne for some considerable length of time, would be joined by a thick layer of toxic ash produced by the intense firestorms that would engulf entire regions of the planet in the days, weeks, and months after the initial event.

To our ancestors this period of absolute darkness might have led them to assume that the sky wolves, in other words, the comet fragments, had quite literally devoured the sun and moon. Clearly, the lack of any sunlight heating up the planet would have resulted in an immediate drop in temperature, helping to trigger the onset of an ice age in a matter of days. Indeed, it would have happened in a manner quite similar to that portrayed in Roland Emmerich’s disaster movie

The Day After Tomorrow

(2004). Although fiction, this film adequately shows what would happen under such severe weather conditions and how quickly our world would be turned on its head by an initial catastrophe of global consequences.

The effect of all this would have been to bring humankind to its knees as it strived to survive from day to day, all this being “caused” by the intrusion into their midst of perceived supernatural creatures, including deathly serpents and terrifying sky wolves that could quite literally swallow the sun and moon whole.

It must have been an unimaginably frightening time to live in. Never would this dreadful age be forgotten; nor should it be forgotten. As Donnelly so aptly put it:

What else can mankind think of, or dream of, or talk of for the next thousand years but this awful, this unparalleled calamity through which the race has passed?

A long-subsequent but most ancient and cultivated people, whose memory has, for us, almost faded from the earth, will thereafter embalm the great drama in legends, myths, prayers, poems, and sagas; fragments of which are found to-day dispersed through all literatures in all lands.

25

The peoples of Northern Europe almost certainly preserved their memory of this “unparalleled calamity” in their accounts of Ragnarök. Its existence helps strengthen the case for canids—wolves, hounds, and foxes—being seen by our ancestors not just as dangerous cosmic tricksters with the power to bring about death and destruction but also as outright enemies of the world pillar, or sky pole, that connects this world with both the underworld and sky world. Yet as we see next, these myths existed not only in “legends, myths, prayers, poems, and sagas”

26

handed down from some forgotten age. They lingered on in fragmentary sky lore that once again reveals the great threat that the sky wolves were seen to pose in destabilizing everything that we have ever held dear in this world.

16

THE WOLF PROGENY

T

he dual relationship between order and chaos in the heavens is highlighted in the “magnificent song of Eirek,” ca. 950 AD, which has the Norse god Odin say: “Evermore the wolf, the grey one, gazes on the throne of the gods,” an allusion to the Pole Star, which in Anglo-Saxon tradition was the “divine seat where the north star Tir (or Tyr) . . . ‘never flinches.’”

1