gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (10 page)

It is a grand title, the

triangle d’or,

but it does seem to express the sheer genius of inspiration that led to the emergence of sites such as Göbekli Tepe, with their unique architecture, which seems almost alien to the modern world. Yet where did this genius of inspiration come from? Dr. Mehrdad R. Izady, professor of Near East studies at New York University, wrote in 1992 (two years before Klaus Schmidt first visited Göbekli Tepe) that at the beginning of the Neolithic age the peoples of southeast Anatolia “went through an unexplained stage of accelerated technological evolution, prompted by yet uncertain forces.”

11

What exactly were these as “yet uncertain forces”? Were they material or divine? Were they human or something else altogether? All we can say is that something quite extraordinary happened in the

triangle d’or

some twelve thousand years ago, and the key to understanding this mystery might well await discovery among the T-shaped pillars and carved art of Göbekli Tepe.

To date, seven major structures (Enclosures A, B, C, D, E, and F, as well as the Lion Pillar Building) have been explored at Göbekli Tepe. Yet the geomagnetic survey undertaken in 2003 suggests that this constitutes just a small fraction of what lies buried beneath the occupational mound (Schmidt estimates there might be as many as fifteen more enclosures still to be uncovered, providing a total of some 200 standing pillars

12

). As can be imagined, with two digging campaigns a year (April to May and September to November), Klaus Schmidt’s multinational team is constantly discovering new structures and monuments.

Very gradually our fragmented picture of what went on here as much as twelve thousand years ago will slowly take shape. Trying to unravel its mysteries too soon is rife with problems, although simply stepping aside and allowing the archaeological evidence to speak for itself is to miss an opportunity to get inside the minds of the Göbekli builders and truly know what motivated them to give up their hunter-gatherer lifestyle to create monumental architecture on a scale never before seen in the world. Why exactly did they do this? Why create the earliest known megalithic monuments anywhere in the world? One possible clue is the strange carved symbolism on the stones that includes quite specific glyphs or ideograms, which, as we see next, might well reveal the Göbekli builders’ fascination with the heavens.

4

STRANGE GLYPHS AND IDEOGRAMS

T

he eastern central pillar (Pillar 18) in Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosure D sports a wide belt on which are a sequence of abstract glyphs, or ideograms, which are likely to have had some symbolic meaning to the Pre-Pottery Neolithic world of the tenth millennium BC. One, looking like a thin letter C, is seen sometimes turned toward the left and at other times toward the right. Another glyph, resembling the letter H, is found both in an upright position and rotated 90 degrees (see figure 4.1 and

plate 11

and

plate13

). It appears in the same sequence as the C-shaped glyphs, and both seem to work in concert with each other.

On the “front” of the T-shape’s belt the H symbol appears no less than five times, two upright and three on their side. In addition to these glyphs is another, slightly larger ideogram that appears in the position of the figure’s belt buckle, below which a fox-pelt loincloth appears in high relief (both are explored in chapter 12).

THE H GLYPH

How might we interpret these strange ideograms in use among the Göbekli builders so soon after the end of the last Ice Age? Let’s start with the H glyph. Searching the archives of prehistoric symbolism throws up very little. They could be shields made of animal hide, as examples in prehistoric art do occasionally resemble the letter H. Yet if so, why do they appear so many times on the same pillar? Also apparent is that the H character resembles two letter Ts joined stem to stem. It is an association that might not be without meaning, especially in view of the general appearance of the T-shaped pillars at Göbekli Tepe and the presence of the twin monoliths at the center of the enclosures. If so, then what might this mirrored double T actually represent?

Figure 4.1. Mid-section of Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 18 in Enclosure D showing the figure’s wide belt decorated with C- and H-shaped glyphs.

Is it possible that the H glyph conveys the connection between two perfectly mirrored worlds, states, or existences linked by a conceived bridge or tunnel, represented by the crossbar between the two “columns”? If this is the case, it really does not matter whether the glyph is depicted upright or rotated 90 degrees; the meaning would always be the same.

SHAMANIC POT STANDS

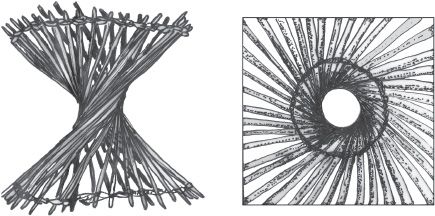

Some idea of how indigenous cultures have portrayed the relationship between the two worlds, and the transition between the two, can be found in the design of ritual pot stands used by the Desana shamans of Colombia. Taking the shape of an hourglass, that is, two cones point to point, they are made from spiraling canes bound together in such a manner as to leave a central hole connecting the two cones, which, when looked at from either end, have the appearance of a hole-like entrance through a spiraling vortex or whirlpool (see figure 4.2). Yet “when seen in profile, as an hourglass, the object can be interpreted as a cosmic model, the two cones connected by a circular ‘door’, an image that leads to others such as ‘birth’, ‘rebirth’, the passage from one ‘dimension’ (

turí

) to another while under the influence of a narcotic, and to similar shamanistic images. . . . In sum, the hourglass shape contains a great amount of shamanistic imagery concerned with cosmic structures and with transformative processes.”

1

These are the words of anthropologist Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff (1912–1994), who conducted an extensive study of the beliefs and practices of shamanic-based cultures of the Amazon rainforest. He saw the hourglass-shaped pot stand of the Desana as symbolic of the connection between the two worlds, the hole created between the two cones being the point of entrance and exit between the two dimensions of existence. This bears out the interpretation of Göbekli Tepe’s H glyph as being a mirrored symbol of movement between two worlds, whether across space or time. If so, then it is likely that the accompanying C glyph also has some kind of transformative role. It would not be unreasonable to see the twin C shape as the slim crescents of the old and new moon, which when shown together, face to face, signify the transition period between one lunar cycle and the next.

Figure 4.2. Desana shaman’s ritual pot stand from the side and looking down through its hollow interior (after Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff).

AUSTRALIAN ABORIGINAL ART

Another possible interpretation of the C-shaped glyph can be found among the symbolic art of the aboriginal peoples of Australia. Here the C-shape ideogram depicts a bird’s-eye view of a seated man or woman, the arms of the symbol representing those of the individual.

2

When two Cs are shown together, face to face, this denotes two people sitting opposite each other.

3

Occasionally there will be a bar shown between them, signifying a small, benchlike mound constructed for special ceremonies and said to symbolize a mound of creation associated with a primeval snake.

4

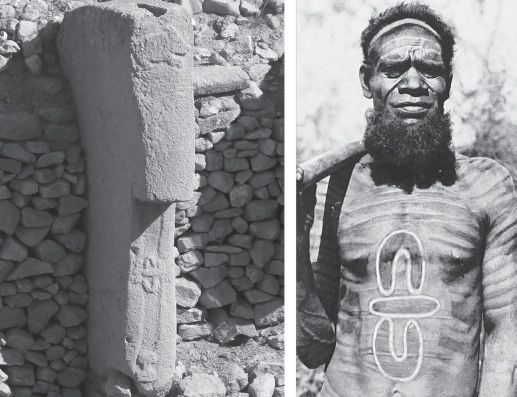

A photograph in British anthropologist Sir Walter Baldwin Spencer’s book

Across Australia

(1912) of a Worgaia medicine man from Central Australia, who was himself “a great maker of medicine men,”

5

shows the double C ideogram, with a bar in between, painted on his chest. It is nearly

identical

to one that appears on the chest of a T-shaped pillar at Göbekli Tepe (see figure 4.3 on p. 54),

6

the only difference being that here the horizontal line forms the connecting bar of the H symbol earlier described.

EMBLEMS OF OFFICE

Like other major pillars at Göbekli Tepe, Enclosure D’s central monoliths have carved symbols upon their “neck,” just below their T-shaped heads. On the eastern pillar two are seen, the uppermost being the same H-shaped glyph found on the belt. This particular example is upright with a small, hollowed-out oval shape within its crossbar (here the symbol looks like two matchstick men holding hands, which lends credence to the idea that the C-ideogram might sometimes mean a seated man or woman, just as it does in Australian aboriginal art). Immediately beneath the H shape is a well-defined, horizontal crescent, its horns turned upward. Cupped within its concave form is a wide-banded circle with a deeply incised hole at its center. A thin, V-shaped “collar” or “chain” is visible either side of the two glyphs (see figure 4.4 on p. 56), making it clear that these symbols are emblems of office worn around the neck, perhaps denoting the individual’s status or identity.

Figure 4.3. Left, double C and H symbol on the chest of Pillar 28 in Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosure C. Right, Worgaia medicine man from Central Australia with the same symbol on his body.

Confirming the use of collars or chains by the elite of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic is a life-size statue of a man, 5 feet 9 inches (1.8 meters) in height, found at Şanlıurfa, just 8 miles (13 kilometers) from Göbekli Tepe (see

plate 23

). Located today in the city’s archaeological museum, the figure was discovered in 1993 on Yeni Yol Street in Balıklıgöl, the oldest part of the city, where a Pre-Pottery Neolithic A settlement was investigated in 1997.

7

It is here also in Balıklıgöl that the prophet Abraham is said to have been born within a cave shrine renowned throughout the Muslim world as an important place of pilgrimage. The statue, which has black obsidian disks for eyes, a prominent nose, arms that end in hands clasped over the genitalia, and a conelike lower half where the legs should be, dates to around 9000 BC. The fact that it also sports a double V-shaped collar in high relief is evidence that the neck emblems on the T-shaped pillars at Göbekli Tepe are most likely pendants or medallions attached to a chain or collar of office.

THE EYE AND THE CRESCENT

Although it is conceivable that the crescent on the neck of the eastern central pillar in Enclosure D signifies the moon, the carved circle with the hole in its center is more difficult to understand (see figure 4.4 on p. 56). Perhaps it is a representation of an eye, as similar circles with hollow middles act as eyes on the 3-D carving of the snarling predator seen on the front face of Enclosure C’s Pillar 27. The likeness is too close for this to be simply coincidence. So if the circle

is

an eye, then the slim crescent that cups it must form the lower eyelid.

In ancient Egypt the eye was the symbol of the sun god Re (or Ra), while the title Eye of Re was given to various leonine goddesses including Sekhmet, Tefnut, and Bastet, showing the clear relationship between the sun and the all-seeing eye.