gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (9 page)

At the center of the enclosure two enormous twin monoliths once stood. Only their stumps remain in situ, with a large fragment of the western monolith (Pillar 37) being reerected in 2009 under the leadership of German architect and engineering consultant Eduard Knoll. Similar to the central pillars in Enclosure B, a leaping fox appears on its inner face, the animal’s gaze once again directed southward. Estimates suggest that originally Enclosure C’s twin pillars would have stood around 16 feet (5 meters) in height. Yet unlike those of Enclosure B, these examples have not been set within a terrazzo floor. Instead, they are slotted into rectangular grooves cut into raised, steplike pedestals sculpted out of the bedrock.

A large area of smoothed bedrock, elliptical in shape, complete with a pair of rock-cut pedestals that also contain rectangular slots, had earlier been found on level ground 160 yards (146 meters) west-southwest of Göbekli Tepe’s main group of structures. Yet here, in what has become known as Enclosure E, or the

Felsentempel

(German for “rock temple”), no clear evidence of any standing pillars or surrounding structure survives today. This said, it is clear that Enclosure E is of the same general age as Enclosure C.

Adjacent to Enclosure C’s western central monolith is one of the most remarkable T-shaped stones discovered so far at the site. Running down the front narrow edge of Pillar 27 is a 3-D predator, a famished quadruped, with a long bushy tail and emaciated body. Its snarling jaws, complete with carved lines signifying whiskers, reveal a mouth full of razor-sharp teeth. That such a feat of artistic expression was carried out eleven thousand years ago by simple hunter-gatherers seems almost alien, although achieve it they did. As to the identity of this predator, Schmidt believes it is a feline, a lion most probably. Yet the shape of its body, the large incised teeth, and the long bushy tail make a case for its being a canine of some description.

A DOUBLE RING OF STONES

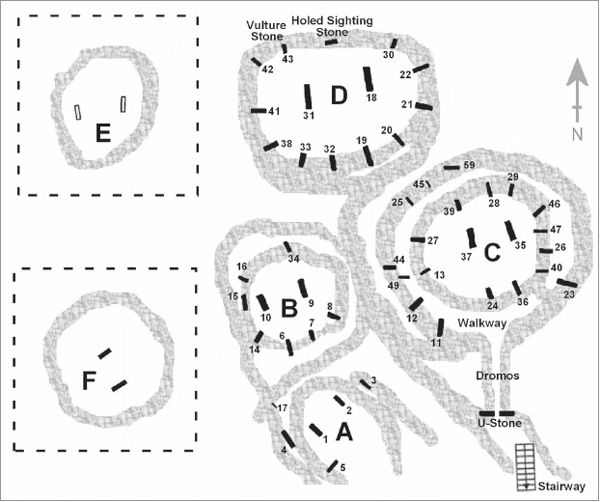

The exact number of standing pillars Enclosure C’s outer ring once possessed is now lost, with just eight remaining in place. Its inner ring probably contained twelve T-shaped pillars, with eleven surviving today. The area between the two concentric walls into which the stones were set created a circular walkway, although there was no direct means of access from here into the central enclosure where the twin monoliths were located. So how might entry have been achieved? The answer is that either a porthole stone once existed within the wall of the inner ring (several such stones, some decorated with carved figures, have been found at the site), or the entrant had to quite literally climb inside, perhaps using ropes or a ladder. This is suggested by the presence of a steplike feature on the south side of the enclosure between two pillars, forming what appears to be an entranceway of some kind (see

plate 7

).

Another possibility is that there was once an overhead entry point within a covered roof. Certainly, there are angled slots and grooves on the upper surfaces of some of the stones making up Enclosure C’s inner circle, which could easily have been cut to help support an overhead structure. Yet whether a roof of this sort was an original feature or one added at some later point remains unclear. Archaeologist Ted Banning of the University of Toronto has proposed that the T-shaped pillars at Göbekli Tepe were primarily roof supports and the enclosures themselves domestic houses,

2

a view not shared by Schmidt and his colleagues.

THE DROMOS

Enclosure C’s circular walkway, between the outer and inner temenos walls, was entered from the south through a north-south-aligned stone passage measuring 25 feet (7.5 meters) in length. Schmidt calls it the

dromos,

after an ancient Greek word meaning

avenue

or

entranceway,

because of its likeness to the passageways attached to the beehive-shaped

tholoi

tombs of Mycenaean Greece.

At the southern end of the dromos a curious U-shaped stone portal, or inverse arch, was set up as an entranceway. The upright terminations of its two “arms” were carved into the likeness of strange, crouching quadrupeds that face outward; that is, away from each other. The identity of these twin guardians, only one of which remains roughly in situ today, is another puzzle (see

plate 8

). Schmidt calls this U-shaped doorway the “Lion’s Gate,”

3

perhaps because of the twin lions carved in stone above the Lion’s Gate entrance at the Mycenaean city of Mycenae in southern Greece.

Beyond the U-shaped entrance to the dromos, Schmidt’s team has uncovered a stone stairway of eight steps constructed to navigate a noticeable dip or “depression” in the bedrock (see figure 3.1).

4

It is an incredible feat of ingenuity and constitutes one of the oldest staircases to be found anywhere in the world. Its presence here at Göbekli Tepe confirms both that an ascent was required to enter the enclosure and that the south was the direction of approach for the visitor.

Figure 3.1. Plan of Göbekli Tepe showing the main enclosures uncovered so far.

ENCLOSURE D

Abutting Enclosure C to the northwest is Enclosure D, the most accomplished of all the structures at Göbekli Tepe. Once again it is ovoid, measuring approximately 60 feet (18 meters) by 47.5 feet (14.5 meters), and would originally have contained a ring of twelve T-shaped pillars (just eleven remain today). Its length-to-breath ratio is almost exactly 5:4, which, strangely enough, is identical to that of Enclosure B

and

Enclosure C, something that is unlikely to be coincidence. (The ovoid outline in the bedrock of the now vanished Enclosure E, located slightly west of the main group of structures, suggests that it too possessed a 5:4 size ratio.) It is a realization we return to in chapter 5.

Two enormous twin monoliths stand at the center of Enclosure D. Although slightly bent by the weight of the soil and debris bearing down on them, they remain intact today. Each one—with a height of around 18 feet (5.5 meters) and weighing as much as 16.5 U.S. tons apiece (15 metric tonnes)—was found to have been slotted into rectangular pedestals carved out of the bedrock, like those in Enclosure C. Yet bizarrely these slots are no more than 4–6 inches (10–15 centimeters) deep, which would have left the pillars particularly unstable.

Such a decision to erect the pillars in this manner is unlikely to have been a design fault, as it seems so out of character with the sophisticated style of building construction employed at Göbekli Tepe. The only logical explanation is to assume that in addition to being slotted firmly into the bedrock pedestals, the central pillars were held in place by wooden support frames (as they are today), which perhaps formed part of a roof.

MYSTERY OF THE FLIGHTLESS BIRDS

The carved decoration on Enclosure D’s eastern central pillar (Pillar 18) is quite extraordinary. Starting with the rock-cut pedestal supporting the monolith, we see a line of seven strange birds spread out along its south-facing edge (see

plate 16

). The peculiar shape of their heads and beaks give them the appearance of baby dinosaurs! However, the creatures’ plump bodies, without any obvious wings, reveal them to be flightless birds that sit on their haunches, their legs stretched out in front of them. So what species do they represent? An examination of known flightless birds from the past right down to the present day suggests they could be dodos (see figure 3.2).

*1

No other bird type known to have existed in the tenth millennium BC even comes close to matching what we see at Göbekli Tepe, and to ignore this conclusion would be to miss an opportunity to better understand the geographical world of the Göbekli builders. This is not to say they visited the island of Mauritius in the Indian Ocean, where the dodo was hunted to extinction by the first Europeans to reach the island, only that somewhere on their travels the Göbekli builders might have encountered a similar bird that is today extinct.

As to why birds of this type are represented at Göbekli Tepe we can only speculate. Perhaps the fact that they are flightless is the clue. Since they can’t fly away, they are rooted to the ground, just like the bedrock pedestals on which they’re carved, implying therefore that the birds symbolize permanence and a point of foundation.

Figure 3.2. Left, seated dodo bird and, right, two of the seven flightless birds seen on the pedestal of Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 18 in Enclosure D.

LATER PHASES OF BUILDING ACTIVITY

Various smaller enclosures and cell-like rooms, uncovered to the north and west of the main group of buildings at Göbekli Tepe, were found to have been constructed during a slightly later building phase, ca. 9000–8000 BC. This seems certain, since they are positioned as much as 50 feet (15 meters) higher than the other enclosures constructed on the bedrock below. In other words, these much younger structures were built long after the older structures had been buried (at least in part) below the gradually emerging tell. Like their forerunners, these rooms contain T-shaped pillars, communal benches, and stone-lined walls, invariably rectangular in design. Yet in size and quality they are often greatly inferior. In some cases, they are the size of bathrooms, with their stones no more than 3.2 to 5 feet (1 to 1.5 meters) in height. Some of the pillars are T-shaped, with clearly carved anthropomorphic features like their predecessors, while others are left unadorned. Clearly the later Göbekli builders were downsizing in architectural style and artistic design, while at the same time retaining some elements of the earlier enclosures.

Around 8000 BC the remaining structures at Göbekli Tepe were covered with fill and abandoned completely, this unique style of architecture continuing only at a handful of other Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites in the region, including Çayönü and Nevalı Çori, which we have already explored; Hamzan Tepe,

5

Sefer Tepe,

6

and Taşlı Tepe,

7

all near Şanlıurfa; and Karahan Tepe.

8

This last mentioned site, set within the Tektek Mountains some 40 miles (64 kilometers) east of Şanlıurfa, has yet to be fully excavated, even though in size it could easily match that of Göbekli Tepe (it was investigated by the present author in 2004, who noted carved stone fragments, exposed heads of T-shaped pillars, a stone row, and countless flint tools scattered across a very wide area indeed). At a place named Kilisik, close to the town of Adıyaman, around 53 miles (85 kilometers) north of Nevalı Çori, a mini T-shaped figure in the form of a small stone statue was found in 1965,

9

leading prehistorians to consider that another early Neolithic site awaits discovery here (see chapter 10 for more on this remarkable statue). At a place named Kilisik, a village close to the Kahta river in Adıyaman province, in the foothills of the Anti-Taurus Mountains, some 46.5 miles (75 kilometers) north-northwest of Göbekli Tepe, a mini T-shaped figure in the form of a small stone statue was found in 1965,

9

leading prehistorians to consider that another early Neolithic site awaits discovery here (see chapter 10 for more on this remarkable stature).

TRIANGLE D’OR

All of these sites, where T-shaped pillars and portable statues have been found, lie within a very small area no more than 150 miles (240 kilometers) in diameter, with its center close to Karaca Dağ, where the genetic origins of modern wheat have been traced to a variety of wild einkorn growing on its lower slopes. This area of southeast Anatolia, where neolithization began, has been christened the

triangle d’or,

the “golden triangle,” due to the key role it played in kick-starting the Neolithic revolution.

10