gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (6 page)

NEOLITHIZATION

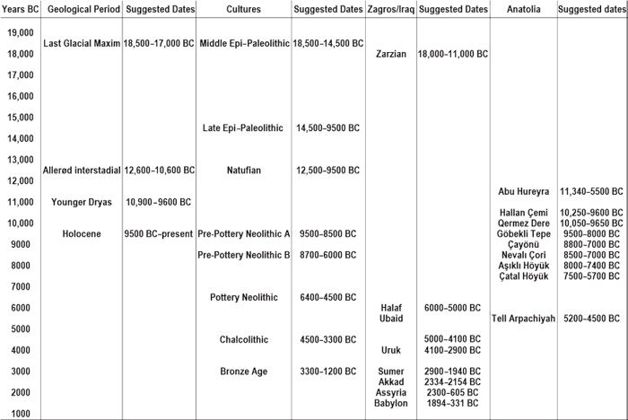

For those who study the prehistory of the Near East, the transitional age between the hunter-gatherers of the late Paleolithic age and the later Neolithic farmers and herders is styled the Pre-Pottery Neolithic, a term devised by British archaeologist Dame Kathleen Kenyon (1906–1978) following her extensive excavations at Jericho in the 1950s. It is a term used much in this book, although in its formative stage this era is described as the proto-Neolithic period, while in Europe this same epoch is called the Mesolithic age (see figure 1.1 on p. 22).

The Pre-Pottery (i.e., preceramic) Neolithic age is split into two separate phases—A and B. The Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) is generally seen to have occurred between ca. 9500 BC and 8500 BC, with the Pre-Pottery Neolithic B (PPNB) taking place between ca. 8700 BC and 6000 BC.

7

This marked the appearance of subsistence agriculture; that is, the domestication of plants and cereals, as well as the growing of crops on a large scale. Thereafter came the Pottery Neolithic, ca. 6400–4500 BC, when “neolithization” really began. It was an age not just of fired pottery but also of the rapid spread of agriculture from Western Asia into other parts of the ancient world, such as Europe, Central Asia, and the Indus Valley of India and Pakistan.

ARCHAEOLOGICAL MINEFIELD

Professor Klaus Schmidt was mainly concerned with the Pre-Pottery Neolithic on his first visit to Göbekli Tepe. He understood full well why the Joint Istanbul-Chicago Prehistoric Survey Team had focused their attentions on Çayönü instead of better investigating Göbekli Tepe, for, as he said himself: “Time was not ripe to recognize the real importance of this site . . . [so] Göbekli Tepe passed into oblivion, and it seems quite clear that no archaeologist returned to the site until the author’s visit in 1994.”

8

Figure 1.1. Chart showing dates of the Near Eastern cultures, civilizations, and paleoclimatological ages mentioned in this book.

Thankfully, Schmidt

did

make the decision to visit Göbekli Tepe and see for himself what the site had to offer, and it took him very little time to realize that beneath the huge artificial mound of reddish brown earth and compacted stone chippings, a Pre-Pottery Neolithic complex of immense significance awaited discovery.

Schmidt also realized that the carved stone fragments scattered about Göbekli Tepe were more than simply funerary slabs belonging to some lost Byzantine cemetery. They closely resembled pillars unearthed at another Pre-Pottery Neolithic site, named Nevalı Çori

9

(see figure 1.2), located on a hill slope overlooking a branch of the Euphrates River, halfway between Şanlıurfa and Diyarbakır, some 30 miles (48 kilometers) north-northeast of Göbekli Tepe. He knew this because he had worked at the site under the auspices of fellow German archaeologist Dr. Harald Hauptmann from 1983 through to 1992, when the rising waters of the Euphrates submerged Nevalı Çori following the construction of the Atatürk Dam.

Figure 1.2. Map showing Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites in southwest Asia mentioned in this book.

THE CULT BUILDING

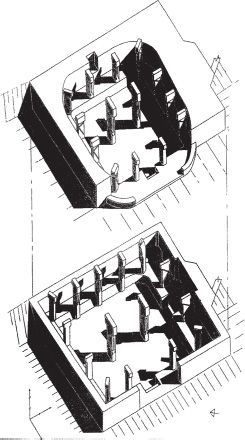

Nevalı Çori was found to consist of a series of rectangular buildings clustered together to form a village settlement, which thrived between 8500 BC and 7600 BC; that is, from the end of the PPNA into the PPNB period. Among the structures uncovered by Hauptmann and his team was one much grander than the rest. Its rear wall backed up to the hill slope, while its interior walls, made of quarry stone, included a communal benchlike feature. This was divided into sections by equally spaced stone pillars, each with a T-shaped or inverted L-like termination. During one of its earliest building phases, designated Level II and dating to ca. 8400–8000 BC, twelve standing pillars had stood within its walls (two on each side and one in each corner), with the number increasing to thirteen during the next phase, designated Level III, ca. 8000 BC (see figure 1.3). Like its counterpart at Çayönü, Nevalı Çori’s megalithic structure possessed a terrazzo floor of burnt lime cement, beneath which was a subfloor of huge stone slabs.

During the Level II building phase, a squared-off niche was constructed into the rear wall of the cult building. Here excavators found an elongated carved head with its face missing. Nicknamed the “skinhead,” it is roughly life size and looks like an egg with ears. On its reverse is a highly unusual

sikha,

a long ponytail that resembles a wriggling snake with its head shaped like a mushroom cap. The “skinhead” originated, most probably, from a full-size statue, which having become detached from its body, had been hidden away within the building’s north wall.

THE GREAT MONOLITH

The item placed within the building’s terrazzo floor, however, was what most compelled the excavators, for standing in the center of the room were the remains of a tall, rectangular pillar bearing an uncanny likeness to the black obsidian monolith that appeared among the apelike creatures at the beginning of Stanley Kubrick’s movie adaptation of Arthur C. Clarke’s

2001: A Space Odyssey

(figure 1.4).

Figure 1.3. Nevalı Çori’s cult building, showing cutaways for Levels II and III, ca. 8400–8000 BC.

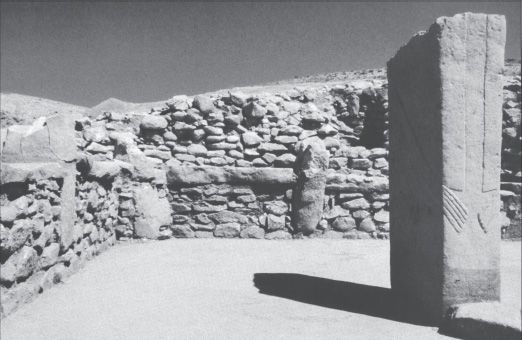

Figure 1.4. Nevalı Çori’s cult building, showing the surviving central monolith still in situ.

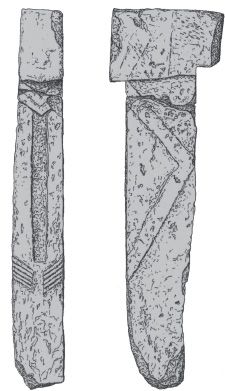

Figure 1.5. One of the stone pillars from Nevalı Çori. Note the stylized arms, hands, stole, and neck pendant.

The pillar, originally 10 feet (3 meters) high, had been carved to represent an abstract human form. In relief across its two widest faces were thin arms, bent at the elbow, with hands and fingers curling around to its front, narrow edge (see figure 1.5 schematic). Anthropomorphic shaping had previously been noted among the remains of the twelve to thirteen standing pillars that had been erected within the building’s four walls, but that displayed on the central pillar was far more accomplished. Above the figure’s hands were two parallel grooves, or chiseled vertical lines, clearly meant to represent the double hem of a woven garment, open to the waist, which some have seen as a scarflike stole, similar to that worn by a Catholic priest.

A broken fragment of the same pillar lay nearby. Its base matched the top of the standing remnant, although its upper end was so damaged that no semblance of the individual’s head could be discerned. In spite of this, it was clear from the presence of the other stone pillars in the walls that this much larger monolith would once have had a T-shaped termination, creating a hammerlike head. As such, it constituted one of the world’s oldest known 3-D representations of the human form.

A hole in the terrazzo floor close to the standing pillar showed that a second monolith must have stood parallel to it, although any trace of its presence had long since disappeared. Like the stone pillars in the walls, the twin pillars perhaps functioned as roof supports, although this is by no means certain. Twin sets of standing pillars had been found in the Flagstone Building and Terrazzo Building at Çayönü. Yet here it was the stone slabs’ wider faces, and not one of their narrow sides, that had greeted the entrant approaching from the south.

A PERSONAL DIVINITY

So who or what did the twin pillars represent? Archaeologists at the time suggested they symbolized a “personal divinity.”

10

This might have been so, but it did not explain why there were two monoliths side by side or why they faced out toward the cult building’s southwesterly placed entrance (the building was found to be oriented almost exactly northeast to southwest). Perhaps the pillars were positioned to greet the entrant, like twin

genii loci

(spirits of the place) guarding the enclosure’s inner sanctum. Very likely this presumed liminal, or sacred, area signified an otherworldly environment that existed beyond the mundane world. Indeed, it probably reflected the presence of a parallel realm, a supernatural world, accessible either in death or through the attainment of deathlike trances and other forms of altered states of consciousness, with the aim being to communicate with power animals, great ancestors, and mythical beings.

11

EXPLORING GÖBEKLI TEPE

Klaus Schmidt had all this in mind as he examined the various carved fragments of “large-scale sculptures”

12

found scattered about Göbekli Tepe. Quickly, he realized that “the entire area had been used for the construction of megalithic architecture, not just a specific part of it.”

13

He saw its function as ritual in nature.

14

Indeed, Göbekli Tepe’s building structures would, he felt, reflect the same cultic influences as those at Çayönü and Nevalı Çori.

Having seen enough, Schmidt came to a frightening conclusion. If he did not turn around and walk away now, he would be there for the rest of his life. As fate would have it, he decided to stay and commit himself to excavating the site fully, and we can be thankful for Schmidt’s decision, as it was afterward discovered that the entire hillside was about to become an open quarry to supply rock for the construction of the new Gaziantep to Mardin highway, a decision that was reversed only when the importance of the archaeological site became known.

15

So we can be pretty sure that without the intervention of this quick-thinking German archaeologist, the world might never have gazed upon the oldest stone temple in the world.