gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (7 page)

2

MONUMENTAL ARCHITECTURE

U

nder the joint auspices of the German Archaeological Institute and the Archaeological Museum at Şanlıurfa, Dr. Klaus Schmidt started work at Göbekli Tepe in 1995. Very soon his team, made up of undergraduates from German and Turkish universities, as well as fifty local workers of Kurdish, Turkish, and Arab ethnicity, began making remarkable discoveries. Beneath the mound’s topsoil his team came across stone pillars set vertically into the ground. Each one was found to have a T-shaped head like those uncovered at Nevalı Çori.

Two principal structures were investigated between 1995 and 1997 at Göbekli Tepe. One—uncovered immediately west of the solitary fig-mulberry tree with its tiny walled cemetery of modern graves—was a rectangular enclosure that became known as the Lion Pillar Building because of the discovery at its eastern end of twin pillars with carved reliefs of leaping lions on their inner faces (see

plate 17

). The other was called the Snake Pillar Building.

SNAKE PILLAR BUILDING

The Snake Pillar Building was located beneath the southern slope of the occupational mound, some 50 feet (15 meters) lower in depth than the Lion Pillar Building. Designated Enclosure A, it sits on the mountain’s limestone bedrock, suggesting its extreme age. Excavators found it to contain five T-shaped pillars standing about an arm’s length apart from one another. As at Nevalı Çori, they were set within quarry stone walls with stepped benches, a thin layer of clay mortar between each block.

Two pillars stood parallel to each other, with another two placed on the same alignment outside of them; a fifth, south of the central pillars, stood within the perimeter wall, one of its narrow edges facing toward the center of the room (a sixth pillar was found just outside the interior walls). The inner pair of stones acted as a gateway into a round apse containing a hemispherical stone bench, constructed at the rectangular structure’s northwest end; a similar apse had previously been recorded in connection with Çayönü’s Skull Building. As was the case with Nevalı Çori’s cult building and Çayönü’s Terrazzo Building, Enclosure A possessed a perfectly level terrazzo floor that covered the underlying bedrock.

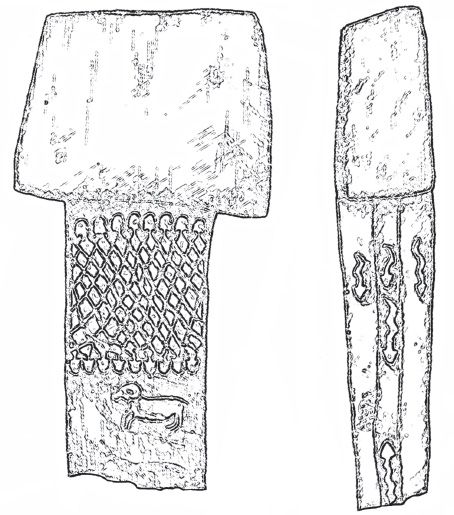

Like the pillars in the Lion Temple Building, those in Enclosure A turned out to be revelations in prehistoric art. Pillar 1, the first to be exposed, bore on its front narrow face five slithering snakes, their heads pointing downward. One of the stone’s wide surfaces displayed more snakes interwoven to form a mesh-like pattern of diamonds, collectively forming a snakeskin pattern (see figure 2.1).

Pillar 2 bore reliefs of an auroch, a leaping fox, and a wading bird, most likely a crane (see

plate 4

). At the top of the pillar’s front narrow edge, just beneath the overhang of the hammer-shaped head, was a small bucranium (ox skull) in high relief. It faced outward toward the viewer, and its whereabouts on the figure made an interpretation easy. Anthropomorphic pillars found at Nevalı Çori had been found to possess a V-shaped relief, like a neck collar, in exactly the same place. In other words, the bucranium was, most likely, a carved pendant or emblem of office, worn around the “neck” of the figure.

CULT OF THE SNAKE

Pillars 3 and 4 were without relief, while Pillar 5 bore yet another representation of a snake. This strong presence of serpentine imagery on the carved stones at Göbekli Tepe begged the question of just what this creature might have symbolized to the peoples of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic age.

Universally, snakes are seen as symbols of supernatural power, divine energy, otherworldly knowledge, male and female sexuality, and, because they shed their skin, metaphysical transformation. The snake also represents the active spirit of medicines, the reason it is today a universal symbol of the medical profession through its association with the cult of Asclepius, the Greek god of medicine and healing. Moreover, the snake is associated not just with beneficial medicines, but also with those that bring forth hallucinations and even death. In Christian legend, for instance, poison offered to John the Evangelist in a laced chalice of wine was made to slither away as a black snake moments before the apostle was about to drink it.

Figure 2.1. Snakes seen on Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 1 in Enclosure A.

Are the snakes carved on the pillars at Göbekli Tepe meant to symbolize the visionary effects of psychotropic (mind-altering) or soporific (sleep-inducing) drugs? It seems likely, for as Schmidt writes himself, several large basalt bowls found at the site were perhaps used in the preparation of medicines or drugs.

1

Visionary snakes are the most common creatures glimpsed by shamans and initiates during ecstatic or altered states of consciousness induced by mind-altering substances, which among the indigenous peoples of the Amazonian rainforest is most commonly the sacred brew called yagé or ayahuasca, known as the “vine of the soul.”

2

These serpentine creatures are seen as the active spirit of the drug and can even communicate with the shaman or initiate.

More pertinent to the decorative art at Göbekli Tepe is that during yagé or ayahuasca sessions, visionary snakes appear in such profusion that on occasion they have been seen to wrap themselves enmass around either the experiencer or nearby houseposts,

3

creating an effect that cannot be unlike the mesh or net of snakes represented on Enclosure A’s Pillar 1 and found also on other standing stones uncovered at the site (see figure 2.2). So is this what the snake imagery at Göbekli Tepe shows, rare glimpses of the visionary world experienced by the shaman? Whatever the answer, the presence of so many snakes in Enclosure A was enough to convince Schmidt to christen it the Snake Pillar Building.

ENCLOSURE B EXPOSED

In 1998 and 1999 a new series of trenches, 29.5 feet (9 meters) square, was opened at Göbekli Tepe. One, dug immediately north of the Snake Pillar Building, revealed the presence of a slightly larger structure, which became known as Enclosure B. This was found to be ovoid, measuring roughly 23 feet (7 meters) by 28.5 feet (8.7 meters), with no less than nine T-shaped pillars—seven placed within its temenos (that is, boundary) wall and two set parallel to each other in the center of a terrazzo floor—like those that had originally stood in Nevalı Çori’s cult building. Schmidt remarked that it was like the “T-shapes,” as he calls the anthropomorphic pillars, were gathered for “a meeting or dance.”

4

Pillar 6 displayed carved reliefs of a reptile and snake, while those set up in the center of the room (9 and 10) both bore T-shaped terminations and exquisitely carved leaping foxes on their inner faces. The creatures’ animated stance made them appear as if they were jumping across the monolith, perhaps toward the entrant who would approach from the south, exactly in keeping with the cult buildings at Çayönü, which also had entrances in the south.

Figure 2.2. Left, poison escapes from the chalice of wine about to be drunk by John the Evangelist in the form of snakes, from a mosaic on the wall of the church of Saint John the Evangelist, New Ferry, Merseyside, England. Right, snakes on the front of Göbekli Tepe’s Pillar 31 in Enclosure D. Do they represent the active spirit of medicines and poisons, or do they refer more particularly to visionary experiences induced through the use of psychoactive substances?

NEW TEMPLES DISCOVERED

Work began around the same time on another structure of much greater size, which became known as Enclosure C. Once again, T-shaped pillars were soon exposed, and these too were set radially within stone walls containing the now familiar stone benches. One monolith, designated Pillar 12, was found to bear a carved relief on its T-shaped head, the first to do so. It showed five birds, either waders or a flightless species, amid a backdrop of V-shaped lines that were perhaps meant to represent water ripples. On the same pillar’s shaft was a “threatening boar”

5

shown above a leaping fox. In front of the stone a portable sculpture of a boar was uncovered. Freestanding art of this kind, including carved human heads, are often found to be fragments of much larger pieces of sculpture, such as carved stone totem poles or life-size statues.

Soon after the discovery of Enclosure C, another massive building structure, Enclosure D, was uncovered immediately to its northwest. This would prove to be one of the oldest and most mysterious monuments ever uncovered in the ancient world. Both enclosures, C and D, are described in full within subsequent chapters.

DELIBERATE BURIAL

What started to become apparent to Schmidt’s team, as it removed the vast amounts of fill that covered the various building structures beneath the tell at Göbekli Tepe, is that each one had been

deliberately

buried beneath an ever-expanding mound.

6

It was almost as if the idea of creating the bellylike tell, or tepe, was part of an original grand design, with each new enclosure playing some role in its greater purpose, a gradually evolving process that had taken some fifteen hundred years to complete. This ritual act of “killing,” or decommissioning, each enclosure before the construction of a new one to take its place would seem to have occurred in stages until around 8000 BC, when the remaining structures were covered over and the site finally abandoned.

7

For Schmidt and his team the burial of the enclosures was an immense bugbear, as it meant they were not easily able to determine the construction dates of the various monuments uncovered. Despite this problem, Schmidt was able to ascertain from the different types of flint tool found within the fill that the

earliest

phases of building activity uncovered at Göbekli Tepe belonged to the epoch known as Pre-Pottery Neolithic A, which began around 9500 BC.

8

THE YOUNGER DRYAS MINI ICE AGE

It is a date that coincides pretty well with the culmination of a mini ice age, or prolonged cold spell, known as the Younger Dryas. This had enveloped much of the Northern Hemisphere for around thirteen hundred hundred years, ca. 10,900–9600 BC, bringing with it a pronounced dip in temperature as well as a sustained drought that severely altered the plant and animal life throughout what is known as the Fertile Crescent. This is the arclike region of verdant river valleys, steppes, and plains that stretches clockwise from Palestine and Israel, through the Levantine corridor of Lebanon, into the Middle Euphrates Basin of northern Syria, then across into what is known as Northern Mesopotamia, a region that embraces southeast Anatolia, before entering the Mesopotamian Plain, or what is today the country of Iraq.

The Younger Dryas period followed a two-thousand-year episode of global warming known as the Allerød interstadial. This in turn had brought to a close the last ice age proper, which had been with us for approximately ninety-five thousand years, reaching its last glacial maximum around twenty to twenty-two thousand years ago (an interstadial is a period when temperatures rise and glaciers go on the retreat).

With the cessation of the mini ice age, or big chill, ca. 9600 BC, the temperatures rose, bringing about a blossoming of new flora and fauna (in geological terms this point in history marks the transition from the Pleistocene age to the Holocene, which we are still in today). It was an ideal environment for new growth that led to the emergence of agriculture on the Middle Euphrates and farther south within the Levantine corridor. It was also around this time, Schmidt believes, that hunter-gatherers from across the region came together to create the extraordinary stone structures being uncovered today at Göbekli Tepe, which he is sure were not domestic in nature.

No evidence of fires, hearths, cooking areas, or any other signs of habitation have been found in or around the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe that might indicate the permanent presence here of a large community. Human remains

have

been found, plenty of them, although these are either retrieved from the fill covering the enclosures or are found concealed in walls or benches. Exactly what they are doing here remains unclear.