gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (14 page)

ANGLES OF ORIENTATION

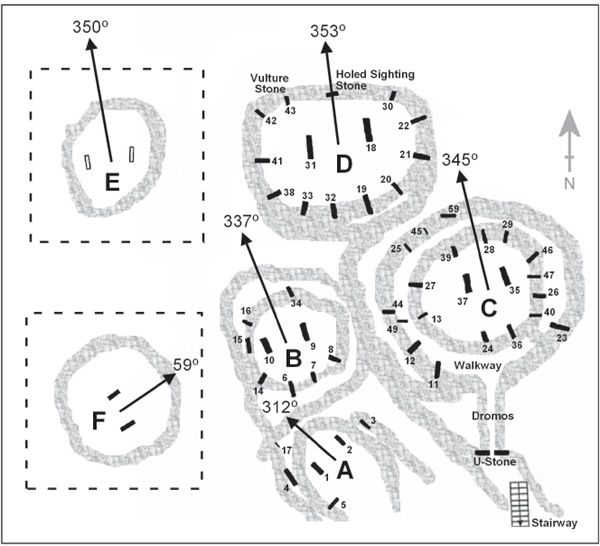

Establishing the precise orientations of the enclosures’ central pillars was put to chartered engineer Rodney Hale, who for the past fifteen years has made a detailed study of stellar alignments at prehistoric and sacred sites around the world. He examined Göbekli Tepe’s detailed survey plan and determined that the central pillars in Enclosures B, C, D, and E (the Felsentempel, or rock temple, located to the west of the main group) all seemed to be aligned just west of north, and, equally, just east of south, in the following manner:

Enclosure B 337°/157°

Enclosure C 345°/165°

Enclosure D 353°/173°

Enclosure E 350°/170°

The twin pillars marking the entrance to an apse-like feature at the northern end of Enclosure A were turned much farther west. Indeed, they are oriented 312 degrees/132 degrees, just 3 degrees off northwest-southeast, suggesting that whatever it was they were oriented toward had little to do with the primary alignments of the larger enclosures.

The slight differences in the mean azimuths of the central pillars in Enclosures B, C, D, and E is telling, as it suggests that each set targeted a star or stellar object that was very gradually shifting its position against the local horizon as a result of precession (see figure 7.1). Thus the enclosures were aligned to a celestial object that either set each night on the north-northwestern horizon or, equally, rose each night on the south-southeast horizon.

AN ORION CORRELATION?

Among the southern star groups and constellations looked at by Hale were the Hyades, Taurus, the Pleiades, and Orion (more specifically its three “belt” stars), all of which have been claimed to match the orientations of the twin pillars in the various enclosures at Göbekli Tepe during the epoch of their construction.

1

Out of these, just one candidate emerged as perhaps playing some role at Göbekli Tepe, and this was Orion, the celestial hunter.

Rodney Hale charted the risings of Orion’s principal stars between 9500 BC and 8000 BC, then matched this information against the window of opportunity created by the orientations of the central pillars in the various enclosures at Göbekli Tepe.

*3

However, the results were disappointing. Although potential alignments existed between Enclosure B and the Orion belt stars between 9000 BC and 8600 BC, the mean azimuths of the central pillars in Enclosures C, D, and E did not target the rising of

any

of Orion’s belt stars between 9500 BC and 8000 BC. The constellation’s other key stars—Betelgeuse, Bellatrix, Saiph, and Rigel—fared even worse, making it highly unlikely that Orion was involved in the orientation of Göbekli Tepe’s principal enclosures.

Figure 7.1. The main enclosures at Göbekli Tepe showing the mean alignments of their central pillars.

ALIGNED TO SIRIUS?

Giulio Magli, a professor of mathematical physics at the Politecnico of Milan, also dismisses Orion’s role in the alignment of the twin pillars at Göbekli Tepe. To accept such a hypothesis, he says, would mean reducing the age of the mountaintop sanctuaries by as much as a thousand years, something that goes against all dating evidence emerging from the site at this time.

2

Instead, Magli proposes that the mean azimuths of the twin pillars in Enclosures B, C, and D were aligned to the rising of the star Sirius, which made its reappearance in the night skies from the latitude of Göbekli Tepe sometime around 9500 BC.

3

For a period of around fifty-five hundred years prior to this time it had been missing from the skies due to the effects of precession. Magli surmises that the hunter-gatherers of the region might have created the temples at Göbekli Tepe to honor the appearance of this new “guest” star in the night sky.

Magli’s theory was put to the test by Rodney Hale. He calculated, by recognized methods, that in the epoch of Göbekli Tepe’s construction, ca. 9500–8900 BC, Sirius, which only just rose above the southern horizon at this time, would have been so dim due to the effects of atmospheric absorption and aerosol pollution that it is unlikely to have impressed the region’s hunter-gatherers.

4

Moreover, the meager arc the star made as it crossed the southern horizon was so brief that in just twenty minutes it would have shifted its horizontal position a full 3 degrees, making it a difficult and highly unrealistic stellar target to use for such a purpose.

5

In conclusion, it seems totally improbable that the Paleolithic peoples of southeast Anatolia gave up their free lives as hunters to worship such an insignificant star. Clearly, if astronomical phenomena really did inspire these people’s building motivations, then it did not involve either the stars of Orion or the lone star Sirius.

NORTH OR SOUTH?

In fact, there is a fundamental problem in even assuming that the main enclosures at Göbekli Tepe are oriented south, for although the humanlike features of the central monoliths are all turned this direction, there is no reason to conclude that their gaze is fixed toward the southern skyline. More likely, they greet the entrant approaching from the south in the same manner that statues in churches face the worshipper approaching the high altar. Church altars are located in the east, as this is the direction of heaven in Christian tradition, and also because churches were often aligned toward the position where the sun rises on the feast day of its patron saint. Just because Jesus, Saint Michael, or the Virgin Mary faces

away

from the high altar does not mean their gaze is fixed toward the western skyline.

In Göbekli Tepe’s case, if its enclosures did have a high altar or holy of holies, then it would have been in the north, the direction of darkness, where the sun never rises. It is also the direction of the celestial pole, the turning point of the heavens. In southeast and eastern Anatolia, northerly orientations of early Neolithic cult buildings have been noted at Çayönü, Nevalı Çori, and Hallan Çemi in the eastern Taurus Mountains (see chapter 23). It thus seems likely that Göbekli Tepe’s enclosures are oriented toward the north, and not the south.

Concluding that Göbekli Tepe’s central pillars face south without taking into account the significance that the north plays in Anatolia’s early Neolithic tradition would be very foolish indeed. What is more, the Sabaeans, the pagan star worshippers of the ancient city of Harran—the ruins of which are overlooked by Göbekli Tepe—each year celebrated the Mystery of the North, since this was deemed the direction of the primal cause and the source of life itself.

6

As we saw in the prologue, the earliest inhabitants of the city, who thrived a full ten thousand years ago, were very likely the direct descendants of the Göbekli builders.

Similar beliefs of the north being the original

qibla,

or direction of prayer, were held by other ethno-religious groups of the region, including the angel-worshipping Yezidi, the Mandaeans of Iraq and Iran, and an Ismaili sect known as the Brethren of Purity.

7

All of them most likely inherited aspects of their beliefs and practices from much earlier cultures with roots in the Neolithic age. With these thoughts in mind, Hale now turned his attention to the northern sky to identify any possible stellar targets there.

TARGET REVEALED

Just one star emerged as a potential candidate, and this was Deneb, the brightest star in the constellation of Cygnus, the celestial bird. Before 9500 BC Deneb was circumpolar, in that it never set, although after this time, through the effects of precession, it started to set each night on the north-northwestern horizon. As the centuries rolled by, the star’s point of extinction moved ever westward in a manner that, as we see below, not only makes sense of the mean azimuths of the various sets of twin pillars at Göbekli Tepe but also offers realistic construction dates for the enclosures in question.

Enclosure D @ 353° = 9400 BC

*4

Enclosure E @ 350° = 9290 BC

Enclosure C @ 345° = 8980 BC

Enclosure B @ 337° = 8235 BC

These dates should not be seen as absolute, as we have no idea as to what level of accuracy the Göbekli builders employed in their building construction. Even a small error in the positioning of the central pillars could alter the proposed alignment toward a stellar object by as much as a hundred years. Having said this, the construction dates of the various pairs of central pillars—suggested by their alignment to Deneb—correlate pretty well with available radiocarbon dates obtained from key enclosures.

ENCLOSURE DATES

For instance, loam taken from wall plaster found in Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosure D has provided a radiocarbon age of 9745–9314 BC,

8

which corresponds perfectly with a date of ca. 9400 BC defined by the alignment of its twin pillars toward Deneb at this time. Interestingly, bone samples taken from Enclosure B have provided a radiocarbon age of 8306–8236 BC,

9

which coincides with a suggested construction date of ca. 8235 BC implied by its twin pillars’ alignment toward Deneb. Having said this, radiocarbon specialist Oliver Dietrich of the German Archaeological Institute believes these burials could have been made long after the construction of the enclosure, so no more can be said on the matter until better dating evidence becomes available.

10

Other radiocarbon dates have been obtained from organic materials found within the fill used to cover the major enclosures, and these range from the late tenth to the late ninth millennium BC, the time of the site’s final abandonment.

11

Clearly, the possibility that the central pillars in Göbekli Tepe’s main enclosures were aligned to reflect the precessional shift of a single astronomical target across an extended period of time is borne out by the astronomical data presented by Rodney Hale. What is more, there is evidence that cult buildings at other Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites in southeast Anatolia might also have reflected an interest in the star Deneb. For instance, the Flagstone Building, Skull Building, and Terrazzo Building at Çayönü are also aligned north-northwest with entrances in their southern walls (see figure 7.2 on p. 84). Hale checked their orientations, based on available plans, and established that they reflect alignments toward the setting of Deneb between ca. 8825 BC and 7950 BC—shown in the following table

12

—dates that accord well with recent revisions of Çayönü’s age based on radiocarbon evidence obtained during the 1960s.

13

| Structure | Azimuth | Deneb Setting Date |

| Flagstone Building | 345.35° | 8810 BC |

| Skull Building | 345.86° | 8825 BC |

| Terrazzo Building | 336.20° | 7950 BC |

CELESTIAL MARKERS

Coming to Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosure E, the Felsentempel, where all the pillars have been removed and only the slots within the stone pedestals remain, we find that the orientation of its twin pillars targeted the setting of Deneb at a date of ca. 9290 BC, some 110 years later than those of Enclosure D (see figure 7.3 on p. 84). This said, the fact that Enclosure E’s standing pillars have been removed makes it impossible to verify whether it really was aligned north toward Deneb. We are, however, on much firmer ground with Enclosure C.

According to Hale’s calculations, Enclosure C’s central pillars targeted the setting of Deneb around 8980 BC, suggesting that this was the time frame of their construction (no radiocarbon dates are available at present for this structure).

*5

Yet the rectangular slots cut out of the bedrock pedestals to support Enclosure C’s twin monoliths are aligned slightly more toward north than the pillars themselves. They are askew only by about a degree, although the difference between the stones and their slots is noticeable. This might indicate that the pillars target Deneb at a date slightly later than the construction of the slots, which could reflect the position of the star at an earlier date. If so, then quite possibly the enclosure is older than the 8980 BC date suggested by the proposed astronomical alignment of its twin pillars, perhaps by as much as a century or so. It is even possible that the monoliths were repositioned when it was realized they no longer synched with the setting of Deneb. So around 8980 BC they were turned very slightly to reflect the star’s new setting position. If this theory is correct, then it is possible that the Göbekli builders were familiar with the effects of precession, which shifts a star against the local horizon at a rate of around one degree every seventy-two years.