gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (15 page)

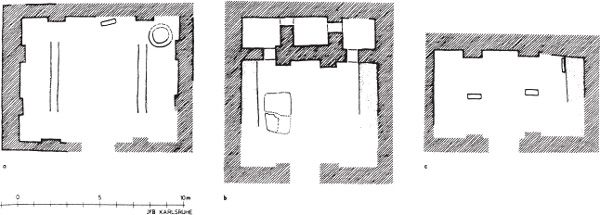

Figure 7.2. The three cult buildings at Çayönü—the Terrazzo Building, Skull Building, and Flagstone Building. All are oriented north-northwest with entrances in the south.

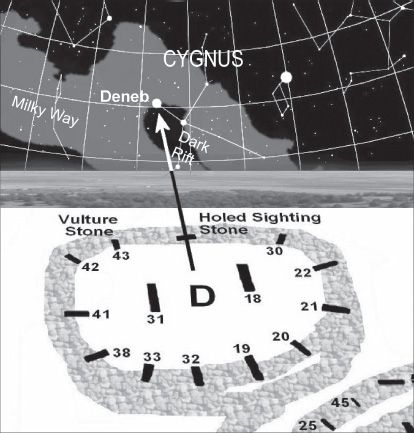

Figure 7.3. The alignment of Enclosure D’s central pillars toward the star Deneb in Cygnus and the opening of the Milky Way’s Great Rift, ca. 9400 BC.

SIGHTING STONE DISCOVERY

Further evidence of Göbekli Tepe’s proposed astronomical alignments comes from Enclosure D. A stone pillar standing around 5 feet (1.5 meters) in height has recently been found in its north-northwestern perimeter wall, exactly behind and in line with its central pillars (see figure 10.3 on p. 109). The stone is rectangular, and unlike the rings of radially oriented pillars found in the main enclosures, it has one of its wider faces turned toward the center of the structure. The significance of this stone is that it has a hole some 9 to 10 inches (23–25 centimeters) in diameter bored through it horizontally at a height of around 3 feet (1 meter) off the ground. Covering the stone is a series of curved lines, which flow in pairs and converge just beneath the hole before trailing off toward the stone’s right-hand corner. Very likely they are a naïve representation of the human torso complete with legs bent at the knees (see chapter 10).

If the enclosure’s twin pillars were indeed oriented toward Deneb, then a person, a shaman perhaps, would have been able to look through the stone’s sighting hole to see Deneb setting on the north-northwestern horizon, a quite magnificent sight that cannot have happened by chance alone. Clearly, this is powerful evidence that the enclosure really was directed toward this star during the epoch of its construction.

A similar holed stone exists in Enclosure C, which is also located within the north-northwest section of the temenos wall (see figure 10.1 on p. 106). Designated Pillar 59, it has been turned over onto its eastern side and is fractured across its hole, with the top section now missing. The diameter of the hole is very slightly larger than the one in the corresponding stone in Enclosure D, measuring 11 to 12 inches (28–30.5 centimeters). This is also the approximate width of the stone through which the hole has been bored.

The holed stone in Enclosure C remains only partly exposed. It leans forward so that no indication of whether it bears any carved relief, like its partner in Enclosure D, can yet be determined. What does seem clear is that when in its original position, Pillar 59 would have stood exactly behind and in line with Enclosure C’s twin central pillars. This means that it too could have been used to observe the setting of Deneb when standing between the twin pillars during the epoch of its construction (bearing in mind that a second, inner ring of stones was added

after

the original construction of the outer circle, according to Klaus Schmidt.

14

Its construction would quite possibly have obscured the line of vision from the twin central pillars to the holed stone).

SOUL HOLES

So what exactly are these holed stones that once stood in the same positions in Enclosures C and D? The answer almost certainly is that they are

seelenloch,

a German word meaning “soul hole” (

seelenlocher,

“soul holes,” in plural). Across Europe

*6

and also in southwest Asia

†7

megalithic structures, such as dolmens, passage graves, and chambered tombs, often incorporate upright entrance stones into which circular holes have been bored. These holes are usually between 10 and 16 inches (25–41 centimeters) in diameter, which makes them too small for an adult to pass through. This has led to speculation that they must have served some kind of symbolic function.

Prehistorians have suggested that the holes in dolmens might have allowed offerings of food to be made to the dead following their initial interment. This is at least possible. Yet more often than not, holed entrances to megalithic structures are interpreted as seelenloch, holes that are believed to allow the spirit or soul of the deceased to exit the tomb. (Even Klaus Schmidt has suggested that fragmented stone rings found at Göbekli Tepe during the earliest surveys of the site might have functioned as seelenloch.

15

This, however, was long before the discovery of the aforementioned holed stones in Enclosures C and D.)

Holes were also bored into the shoulders or sides of cremation urns in Roman Europe,

16

and also in the Ararat Valley of eastern Anatolia during the Bronze Age,

17

apparently with similar purposes in mind. In places such as the Austrian Tyrol the concept of the seelenloch persisted until the twentieth century. Here, circular “doors” were built into the walls of houses, which were opened only when a person died in the house, the purpose being to allow the soul of the deceased to leave its earthly surroundings and depart for the afterlife.

18

CAUCASIAN DOLMENS

By far the greatest concentration of dolmens with façades or entrance stones, into which holes have been bored, are to be found in the Caucasus region of Abkhazia and southern Russia, on the northeast coast of the Black Sea. Here as many as three thousand structures of this kind have been noted, many of which have never been properly recorded. Those that have been investigated produce radiocarbon dates and artifacts suggesting a construction date during the Bronze Age, ca. 3000–2000 BC.

19

Many of the dolmens have paved-stone enclosures with tememos walls that incorporate the porthole stone. The similarity in design between these megalithic enclosures in the Caucasus and Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosures C and D, with their own holed stones forming part of the temenos wall, is uncanny and must surely form part of a similar tradition.

Many of the Caucasian dolmens have carved reliefs around their portholes. Often this shows twin pillars or supports capped with a trilithon (like those at Stonehenge), creating the image of a gateway or doorway, similar to the torii entrance gates to Japanese Shinto shrines. These carved gateways are curiously reminiscent of the twin pillars standing at the center of the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe.

It thus seems likely that the holed stones in Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosures C and D functioned as seelenloch. If correct, then whether this rite of passage through the stone’s bored hole related to souls of the deceased leaving the enclosure or unborn souls entering this world is a matter of debate discussed in chapter 10. More obviously, the seelenloch enabled the soul or spirit of the shaman to exit the structure.

PASSAGE OF THE SOUL

While in an ecstatic or altered state of consciousness a shaman imagines him-or herself entering a hole or tunnel that allows access to otherworldly environments, either in the lower world (underworld) or upper world (sky world). Often these holes, particularly those leading to the lower world, are reached through the visualization of physical holes such as water holes, holes in tree trunks, circular depressions in rocks, entrances to caves, or holes carved in polished circular stones, similar to the jade

bi

or

pi

disks of Chinese folk tradition.

20

These are thought to symbolize the starry vault, with the hole in the center representing the access point to heaven.

21

Siberian shamans often wear on their coats disks with holes, which are usually made of iron. They bear names such as

künjeta

(“sun”) and

oibon künga

(“hole-in-the-ice sun”) and correspond with invisible holes (

oibone

) in the shaman’s body used in spirit communication.

22

This then is what the porthole stones in Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosures C and D most likely signified—points of exit for the shaman’s soul on journeys to the sky world, accessed via the star Deneb in Cygnus. Yet why was this particular area of the sky of such interest to the shamans of the early Neolithic? The answer seems to lie in the fact that Deneb cannot take

all

the credit for causing the Göbekli builders to align the various sets of twin pillars toward the north-northwest. For Deneb’s role as a stellar marker is in fact secondary to the Milky Way’s Great Rift, which, as we find out next, was once seen as an entrance to the sky world.

8

THE PATH OF SOULS;

T

he orientation of the central pillars in Göbekli Tepe’s main enclosures toward both Deneb and the Milky Way’s Great Rift is by no means unique. All around the globe ancient cultures and societies saw this area of the heavens as an entrance to the sky world. It was considered a place of the gods, a land of the ancestors, and the source of creation in the universe.

For instance, the ancient Maya of Central America pictured Xibalba, their underworld, as accessible from a sky road known as

ri b’e xib’alb’a,

the Black Road, identified as the Milky Way’s Great Rift.

1

Its actual entrance or location was represented by cave and mouth imagery, often accompanied by a symbol known as the Cross Bands glyph. This has the appearance of a letter X inside a square frame and has been identified with the Cygnus stars in their guise as a celestial cross, made up of five specific stars.

2

The actual road to Xibalba (a word meaning “place of fear”) is shown as a caiman crocodile, its long jaws the twin streams created by the Great Rift, with its head, eyes, and gullet located in the vicinity of the Cygnus region (see figure 8.1 on p. 90).

In Mayan mythology the solar god One Hunahpu was reborn from the mouth of the caiman. The sun god was perhaps imagined as being carried along the length of the creature’s open jaws to the place where the ecliptic, the sun’s path, crosses the Milky Way in the vicinity of the stars of Sagittarius and Scorpius.

3

This is a point corresponding, visually at least, with the nuclear bulge in the galactic plane that marks the center of the Milky Way galaxy. The sun god reached this point of rebirth at the moment of sunrise on the winter solstice.

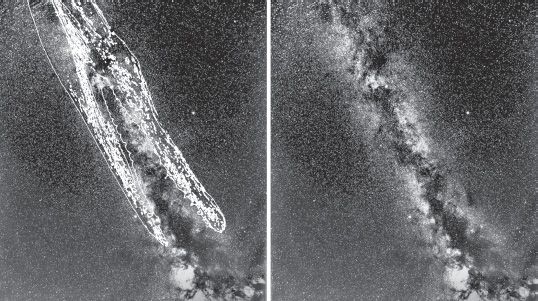

Figure 8.1. Left, caiman crocodile overlaid on the Milky Way’s Great Rift, as conceived by the Maya of Central America. Right, the Milky Way’s Great Rift on its own for comparison.

The Olmec of Mexico, whom the Maya might well have seen as spiritual forebears, created grotesque stone offering tables with the likeness of the head and jaws of a monstrous jaguar. From the creature’s open mouth (some see it as a cave entrance) a deity identified as a were-jaguar—half human, half jaguar—is seen emerging. Although next to nothing is known about Olmec cosmology, it probably involved mythological ideas similar to those of the Maya.