gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (19 page)

Figure 10.5. Ancient Egyptian sky goddess Nut in her role as a personification of the Milky Way, with the stars of Cygnus marking her womb and vulva, and the Great Rift signifying the gap between her legs (after R. A. Wells).

BIRTH CHAMBER

How exactly the entrants to Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosure D, or indeed its neighbor, Enclosure C, might have celebrated the act of cosmic birth is open to speculation. Perhaps the new soul was believed to emerge from the opening of the Great Rift and then in some unimaginable manner enter a pregnant woman waiting between the enclosure’s twin pillars. A ritual act like this might have taken place either at the point of conception, sometime during pregnancy, or, perhaps, shortly before birth. It might even be that some births actually took place between the enclosure’s central pillars, mimicking exactly what the incised lines on the holed stone were attempting to convey.

So not only were the enclosures at Göbekli Tepe built to honor the departure of the soul in the company of the vulture in its role as psychopomp (remember, the Vulture Stone is next to Enclosure D’s holed stone or Cosmic Birth Stone, as we shall call it), but they were also designed to bring forth new life. Presumably souls entering the world would be accompanied by a psycho-pomp in the guise of a bird, most probably the vulture, which in some painted panels uncovered at Çatal Höyük is shown with an oval inside its back containing a human baby. Today, in many parts of Europe and Asia newborn babies are accompanied into the world by the stork. Yet in the Baltic (and seemingly in Siberia

4

) a white swan replaces the stork.

5

Clearly, in these areas of the globe, the swan or stork plays the same role as the vulture once did in the Near East.

In Egyptian and Hindu myth, a primordial goose or swan brought forth the universe with its call, although in many countries the swan was said to have laid the egg that either formed the universe or became the sun (such as Tündér Ilona, the Hungarian fairy goddess, who “when she was changed into the shape of a swan” laid an egg in the sky that became the sun

6

). This once again ties in with the belief that cosmic creation takes place in the vicinity of the Cygnus constellation and Great Rift, resulting in the rebirth of the sun each day.

COSMOLOGICAL BELIEFS

Everything points toward Enclosure C and Enclosure D’s holed stones being not just confirmation of Deneb’s place in the mind-set of the Göbekli builders but also of the site’s role as a place where the rites of birth, death, and rebirth were celebrated both in its carved art and within the architectural design of its larger enclosures, which formed symbolic wombs complete with twin souls and axes mundi.

The Göbekli builders would appear to have used the holed stones as seelenloch to enter an otherworldly environment associated with both the act of cosmic birth and the creation of human souls, which came forth from there prior to childbirth and returned there in death. During their ecstatic and altered states of consciousness, shamans at Göbekli Tepe perhaps believed they were to become as fetuses in order to reenter the cosmic womb, the source of primordial creation, an act integrally associated with the star Deneb and the Milky Way’s Great Rift.

Further confirmation of the holed stones’ function as symbolic vulva is found in the work of scholars attempting to understand the cosmic design of megalithic dolmens, which, as we know, often have circular holes in their entrance façades. The burials found inside them are often placed in fetal positions ready for new life, leading to theories that the stone structures are symbolic wombs or uteri, their portholes representing the vulva, prompting one expert on the origins of Judaism and Islam to observe that whosoever “enters or leaves a dolmen [through the hole “drilled with enormous effort”] does this in the posture of a child at delivery through the vagina. The burial-dolmen itself is therefore symbolically a uterus.”

7

These are incredible revelations that entirely alter our current perceptions of the mind-set of those behind the creation of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic world in southeast Anatolia. Yet as we see in part three, such cosmological thinking pales into insignificance when compared with other major factors that might well have been behind the creation of Göbekli Tepe’s main enclosures. For it seems likely that monumental architecture on this scale was built in response to something terrible that had happened in the world.

PART THREE

Catastrophobia

11

THE HOODED ONES

U

p to twelve T-shaped pillars stood in rings within Göbekli Tepe’s large enclosures, all with their faceless gaze focused toward the central monoliths, as if they formed part of some kind of otherworldly gathering of a secret society. For when we come to ask why the human form is being portrayed with T-shaped terminations both here and at other Pre-Pottery Neolithic sites across the region, with the best answer being that they represent individuals with heads that are long and narrow (hyper-dolichocephalic) who also wear cowls, or hoods, that extend to the rear, as if they might cradle a full head of hair.

It is a conclusion strengthened in the knowledge that the life-size statue of a male uncovered during urban development on Yeni Yol Street in Şanlıurfa’s Balıklıgöl district in 1993, has a regular face and head, as do the various portable statues found at Göbekli Tepe and Nevalı Çori. So the sculptors of the Pre-Pottery Neolithic world knew very well how to create perfect representations of the human form with all its intricacies. Clearly then, the T-shaped pillars are abstract representations of those remembered as having once

looked

this way, their blank expressions confirming their otherworldliness, or transcendental nature.

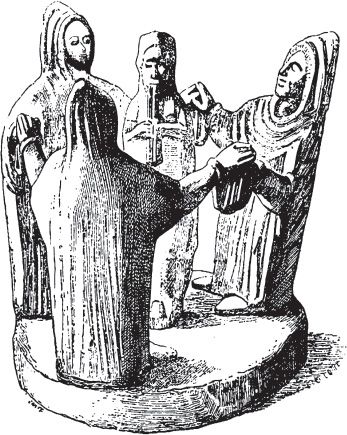

Figure 11.1. An example of hooded figures in a circle, like the T-shaped pillars at Göbekli Tepe. Here three men perform a type of dance around a piper. Cyprian limestone carving. Phoenician in origin, date unknown.

THE MINI T-SHAPED STATUE

That the T-shaped pillars show long-headed individuals wearing cowls seems confirmed by the mini T-shaped statue found in 1965 close to the village of Kilisik, some 46.5 miles (75 kilometers) north-northwest of Göbekli Tepe. It appears to be wearing a large hood extended at the rear by the peculiar shape of the skull; indeed, even the start of the hood can be seen as a straight line that divides the rear half of the head from the projecting face (see figure 10.2).

Why exactly these figures are depicted with elongated heads is a matter we return to later in this book. Yet why wear hoods or cowls in the first place? Perhaps it was the prevailing climatic conditions, or the fact that these individuals needed to protect their skin from the sun’s rays. More likely is that the cowls convey some idea of status among the communities in which they moved, a fact suggesting the presence of elitism; in other words, a clear division between the Göbekli builders, made up of quarry men, stone masons, flint knappers, hunters, and butchers and those who controlled and managed the construction work going on at the site.

Having said this, it seems unlikely that the T-shapes reflect the presence of individuals living when the main enclosures at Göbekli Tepe were constructed around 9500–8900 BC. Like saints and divinities represented as carved art in churches, or the statues of gods and heroes in classical temples, the T-shapes at Göbekli Tepe are perhaps reflections of something that has been. Something that had to be remembered, celebrated, and not forgotten.

We cannot know what might have been going at Göbekli Tepe when the large enclosures were under construction, nor whether the genesis of the T-shaped pillars happened here or elsewhere. It

is

possible, as Schmidt believes, that complex structures like Enclosures C and D were the pinnacle of a long period of development at the site going back many thousands of years. On the other hand, the construction of the monumental enclosures might just as easily have been inspired by a significant event. Perhaps the arrival in southeast Anatolia of representatives from another culture—individuals who helped galvanize the local hunter-gathering population into embarking on this mammoth building project.

A SUDDEN CHANGE IN LIFESTYLE

Is this what really happened in southeast Anatolia sometime either during or directly after the Younger Dryas mini ice age, ca. 10,900–9600 BC? Did some great change occur in the world of the local hunter-gatherers that culminated in the construction of the large enclosures at Göbekli Tepe under the guidance of some kind of “power elite,”

1

as Schmidt refers to them?

Hunter-gatherers would work together in small bands to fulfill their primary functions in life, with these being hunting wild game, foraging for various types of food, and ensuring the well-being and safety of their extended family group. They created temporary settlements that they occupied only at certain times of the year; for the rest of the time the hunters followed the migrational routes of herd animals. They relied on these animals for food; clothes; fat for balms, fires, and lamps; bone, horn, and antler for weapons, tools, and items of personal adornment; and sinew (thin shredded fibers of muscle tendons) for use as cordage, binding points on arrow shafts, and as a backing material on bows.

Epipaleolithic (that is, transitional Paleolithic) hunters used established campsites and work stations, kitted out with basic facilities, before moving on to the next site, and the next site, and so forth, until eventually they returned to their original place of departure. This was their cycle of life, and it would have remained so had neolithization not gotten in the way.

There can have been no obvious advantage in hundreds, if not thousands, of people (Klaus Schmidt believes that between five hundred and a thousand individuals were employed in building construction at Göbekli Tepe at any one time

2

) putting aside their free existence as hunters and foragers and coming together to create monumental architecture on such a grand scale. Something must have spurred the regional population into abandoning their old lives and adopting a completely different way of living, and from the presence in the enclosures of the massive T-shaped pillars, that “something” would appear to have been whoever, or whatever, they represented.

Did the T-shapes represent the memory of powerful individuals, great ancestors perhaps, of those who built Göbekli Tepe?

MESSIANIC MESSAGE

If so, then who exactly were these influential figures—the Hooded Ones, as we shall call them until their likely identity is revealed? Did they come as messianic figures, bringing some sort of message—one that was so clear it could not be ignored? Was it believed that something bad would happen to the local hunter-gatherers, their families, and the world around them if this message were to be ignored?

As much as these ideas might seem at odds with our understanding of the Paleolithic mindset, they will begin to make sense of the evidence being uncovered right now at Göbekli Tepe. This can be seen in the fact that the continuous building of sacred enclosures in the same basic style, albeit in a gradually

declining

fashion, across a period of nearly fifteen hundred years, ca. 9500–8000 BC, argues for the presence at the site of a very rigid belief system attached to the erection of the T-shaped pillars. It implies also a strength of conviction that might be compared to the manner in which Christians, adhering to ancient traditions, have steadfastly built churches in the same basic style across a very similar period of time.

The same can be said for the religious houses of other major religions, with the motivation behind these strictly-adhered-to dogmas always being the words, deeds, and legacy of prophets, saints, and messianic figures. Had something similar been going on at Göbekli Tepe or more particularly in the world that existed immediately prior to the construction of its large enclosures?