gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (22 page)

14

FROM A FOX TO A WOLF

I

n the star lore of Estonia, on the Baltic coast of Northern Europe, we again encounter Alcor, the Fox Star, although now its zoomorphic form has changed to that of the wolf (

bar

in Estonian). As the Wolf Star it stands alongside the Ox, or Bull, identified with the nearby star Mizar.

1

Once again they constitute the kink of the “handle” of the Big Dipper, or Plough, which in Estonia is known as the Great Wain (that is, a cart or wagon).

Slovenian star lore tells the story of Saint Martin, who uses the Great Wain (Ursa Major) to carry a great pile of logs.

2

Along comes the mischievous Wolf (Alcor), who proceeds to kill the Ox (Mizar) and break the vehicle’s shaft. The saint repairs the Wain and, as punishment, harnesses the Wolf to the Ox in order to make the animal take the load. Yet the Wolf does nothing more than pull the cart backward.

THE CESSATION OF COSMIC TIME

Once more the star Alcor, here in the guise of the Wolf, is seen to interfere with the turning mechanism of the heavens, symbolized in this instance by the shaft of the Wain. Not only this, but he also disrupts the natural order of the heavens by dragging the wagon backward, an allusion to the collapse or reversal of time. Clearly, in European star lore the figure of the sky wolf was interchangeable with that of the sky fox.

The harnessing of the Wolf (Alcor) by Saint Martin is simply a variation of the Romanian sky myth in which the Man defeats the Devil to restore cosmic order. Clearly, the wolf, the fox, and the Devil play nearly identical roles in this myth cycle, with the human intercession being necessary to prevent any kind of catastrophe taking place (the role played by the shaman at Göbekli Tepe).

Saint Martin’s feast day is November 11, when swans and geese are roasted and eaten across Europe. The date corresponds also to the return of migrating swans and geese from their breeding grounds in the north. Indeed, the idea of swans and geese carrying souls to and from a northerly placed “heaven” played a major role in European folklore until fairly recent times, the connection with Cygnus in its capacity as the entrance to the sky world being the obvious next step.

3

Thus if Saint Martin might be seen as a Christian patron of the Cygnus constellation, then his role in the Slovenian sky myth makes complete sense. Like the Man in the Romanian story, he is the guiding intelligence of the Cygnus constellation in its struggle against the cosmic trickster symbolized by the star Alcor in Ursa Major. More incredibly, these beliefs almost certainly go back to a time when the constellation of Ursa Major revolved around either Deneb or Delta Cygni in their role as pole stars, ca. 16,500–13,000 BC.

Yet even if this unprecedented vision of the beliefs and practices of those who inspired the construction of Göbekli Tepe in the tenth millennium BC is correct, why go to all this trouble in order to avert the baleful influence of comets? What was the real motivation behind all this work and effort, which must have completely changed the lifestyles of the hunter-gatherers of the region? Why did anyone at the end of the Upper Paleolithic age live in fear that a sky fox, or indeed a sky wolf, might disrupt the turning mechanism of the heavens and in so doing bring about the destruction of the world?

The answer would seem to be that in the minds of the Göbekli builders, there was a genuine fear that if they did

not

do everything in their power to curtail this perceived threat from the sky, then something bad would happen. Whatever that “something” was, it was so deeply entrenched in the collective psyche of the peoples of southeast Anatolia that they were willing to abandon their old lifestyles and adopt new ones in order to deal with the problem.

Accepting such a scenario only makes sense if there had already been a terrifying incident involving the sky fox or sky wolf—one that had brought chaos to the world during some former age of humankind. As we see next, a search through the folklore, myths, and legends of the ancient world tells us that just such a catastrophe might well have taken place in fairly recent geological history.

15

TWILIGHT OF THE GODS

I

t was the American congressman, popular writer, and amateur scientist Ignatius Donnelly (1831–1901), most remembered for his best-selling work

Atlantis: The Antediluvian World

(1882), who first publicly explored the possibility that a comet impact caused untold devastation on earth during some former geological age. More significantly, he thought that humans living at this time might well have preserved a memory of this catastrophic event that was passed down through countless generations in the form of myths and legends.

Donnelly’s theories on a comet impact in recent geological history became the subject of a book entitled

Ragnarök: The Age of Fire and Gravel,

published in 1883, just one year after

Atlantis: The Antediluvian World

. It contains myths, legends, stories, and traditions from around the world that preserve chilling accounts of something immensely bad that happened in our skies, involving the sun, moon, and intruding celestial phenomena. As a result the earth is decimated by an all-encompassing conflagration, accompanied by noxious clouds, an extended period of darkness, and a subsequent deluge, responsible for putting out the fires

and

drowning humankind. Invariably, just a few righteous people survive, either by boarding a vessel or by hiding in a cave. Very often the world is repopulated either by a single family or a couple, usually a brother and sister, who become the progenitors of a new group of humans. Some accounts even speak of the survivors erecting great temples as a direct response to what has happened.

THE EDDAS

One source of material utilized by Donnelly to outline the actions of what he saw as a rogue comet, or cluster of comets, that brought destruction to the world, was that preserved by the peoples of Scandinavia and Iceland. Two primary sources are cited—the

Prose Edda

and

Poetic Edda

(known also as the

Younger Edda

and

Elder Edda

)—both recorded in their present form by Christian scholars during the medieval period. The

Prose Edda,

attributed to Snorri Sturluson, who lived ca. 1178–1241, derives from an Icelandic text known as the

Codex Upsaliensis,

which dates to the early 1300s, while the

Poetic Edda

is found in a thirteenth-century manuscript, written in Icelandic and known as the

Codex Regius.

Both Eddas feature a much prophesized event that acted as the climax to the age of the gods, who are known as the Æsir, or Asa. This catastrophic event is referred to as Ragnarök, an Old Icelandic word meaning “doom or destruction of the gods; the last day, the end of the gods.”

1

Another variation of the name, Ragnarøkkr, means “twilight of the gods” or “world’s end.”

2

Put simply, it is the Norse version of Armageddon, a fatalistic judgment, where key gods actually die fighting hellish monsters that rise up intent on bringing about the end of the world.

So important was the account of Ragnarök to Donnelly’s mounting evidence for a comet impact in some former age of humankind that it provided him with the title for his book. As there is today overwhelming scientific evidence to confirm his forward-thinking conclusions (see chapter 17), it seems appropriate to allow the U.S. congressman’s often poignant comments to set the scene as we review the account of Ragnarök as given in the

Prose Edda,

Donnelly’s own source for the events described in his book, cited here using the English translation by American author, professor, and diplomat Rasmus Björn Anderson (1846–1936).

3

THE DEVOURING OF THE SUN AND MOON

The twilight of the gods began, according to the Scandinavian account, after the human race had become foul murderers, perjurers, and sinners, shedding each other’s blood. Humanity’s descent into depravity is a common theme in catastrophe myths that generally stress that divine intervention was necessary to purge the world of a wicked or evil strain of humanity.

Thus the scene is set for the coming destruction, and shortly afterward a terrible sight is seen in the skies—the wolf named Sköll opens its jaws and eats the sun. “That is, the Comet strikes the sun, or approaches so close to it that it seems to do so,”

4

was how Donnelly put it.

The Edda tells us next how another wolf named Hati Hróðvitnisson (his first name means “he who hates, enemy”

5

) devours the moon: “and this, too, will cause great mischief. Then the stars shall be hurled from the heavens, and the earth shall be shaken so violently that trees will be torn up by the roots, the tottering mountains will tumble headlong from their foundations, and all bonds and fetters will be shivered to pieces.”

6

These words Donnelly saw as describing the appearance of a second comet, its blazing debris now falling to earth, causing absolute devastation.

7

There is a hint here also of the loosening of the bonds that hold up the sky pole, or world pillar, preventing the world from falling apart.

After this the monster known as the Fenris Wolf, the offspring of the trickster god Loki, breaks free of his shackles, which had held him firm up to this time (see figure 15.1 on below), prompting Donnelly to comment: “This, we shall see, is the name of one of the comets.”

8

Fenris himself is the father of Sköll and Hati, wolves that pursue and devour the sun and moon.

THE MIDGARD SERPENT

The account of Ragnarök continues: “The sea rushes over the earth, for the Midgard-serpent writhes in giant rage, and seeks to gain the land.”

9

This is a mythical snake that curls around the base of the world tree, known as Yggdrasil, which unites heaven, earth (Midgard), and underworld. The Midgard Serpent is for Donnelly “the name of another comet; it strives to reach the earth; its proximity disturbs the oceans.”

10

However, once again we can see here the actions of a terrible monster intent on destroying the physical world by bringing about the downfall of Yggdrasil, the Norse form of the world pillar.

We are told next that the “Fenris-wolf advances and opens his enormous mouth; the lower jaw reaches to the earth and the upper one to heaven, and he would open it still wider had he room to do so. Fire flashes from his eyes and nostrils. The Midgard-serpent, placing himself by the side of the Fenris-wolf, vomits forth floods of poison, which fill the air and the waters.”

11

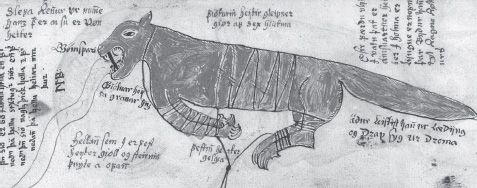

Figure 15.1. The Fenris Wolf bound with magical cord, from a seventeenth-century Icelandic manuscript in the possession of the Árni Magnússon Institute in Iceland. Note the Van River emerging from the creature’s mouth.

These then, the Fenris Wolf and the Midgard Serpent, are to be seen as the two principal comets of destruction, side by side, Donnelly suggested, “like Biela’s two fragments, and they give out poison—the carbureted-hydrogen gas revealed by the spectroscope.”

12

Biela was the name given to a short-period comet first recorded in 1772 and observed again in 1805. It was not, however, recognized as being the same object until 1822, when Wilhelm von Biela, an army officer from Vienna, finally identified it as a periodic comet with an orbit of just 6.6 years. During its appearance in 1852 the comet split in two, prompting Donnelly’s comment about the two comet fragments moving together.

Biela’s comet was never seen again, and presumably it has now broken up into undetectable pieces that periodically fall to earth as harmless meteors whenever the earth passes through the orbit of its remaining fragments. Illustrations of the comet after its breakup into two separate fragments make for a very ominous picture indeed (see figure 15.2), helping us to understand the dread that the appearance of such celestial bodies might have instilled in the peoples of former ages.

After this time the

Prose Edda

states that “Surt rides first, and before and behind him flames burning fire. His sword outshines the sun itself. Bifrost (the rainbow), as they ride over it, breaks to pieces.”

13

Surt is said to have been a fire giant, although for Donnelly it is the “blazing nucleus of the comet,”

14

with swords being common metaphors for comets. For example, an illustration of comet types in Johannes Hevelius’s

Cometographia,

published in 1668, shows them as swords and daggers of various shapes and sizes (see figure 15.3 on p. 140).