gobekli tepe - genesis of the gods (18 page)

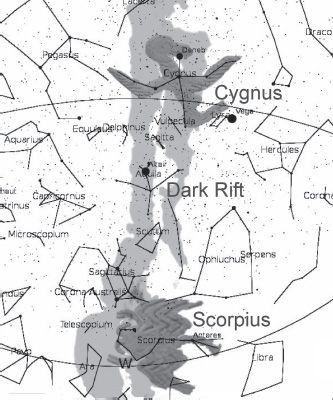

Figure 9.5. The Milky Way’s Great Rift overlaid with the scorpion and vulture from Göbekli Tepe’s Vulture Stone (Pillar 43), showing their match with, respectively, the stars of Scorpius when just above the western horizon and, at the same time, Cygnus (the vulture) as it crosses the meridian high in the sky.

Absolute confirmation of this pictorial journey into the afterlife comes from the fact that in 9500 BC, when Scorpius came into view on the western horizon shortly after sunset, the Milky Way’s Great Rift would have stretched upward into the night sky to highlight Cygnus as it crossed the meridian on its upper transit at an elevation of approximately 70 degrees. It is almost certainly this relationship between the two constellations that is depicted on Göbekli Tepe’s Vulture Stone, especially as the pillar’s clown-footed vulture and scorpion are in similar positions to their celestial counterparts (see figure 9.5).

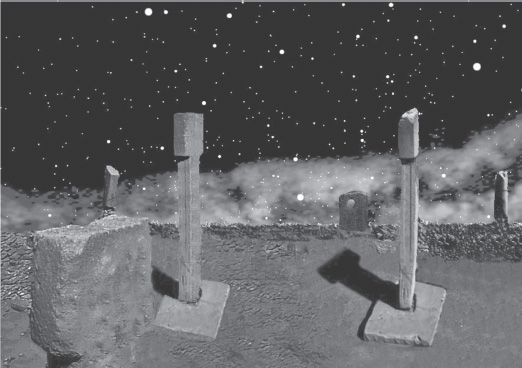

The fact that Enclosure D’s Vulture Stone is also in the north-northwest, next to the holed stone and on the same basic alignment as its twin pillars, is another potential clue as to its astronomical function, in particular its connection with Cygnus and the Milky Way’s Great Rift. Yet how exactly did the Göbekli builders envision the sky world, which seems to have been intrinsically linked to the symbol of the vulture? The greatest clue comes from the holed stone, which, as we have seen, probably acted as a seelenloch, or soul hole, through which the soul had to pass in order to reach its otherworldly destination.

10

COSMIC BIRTH STONE

I

f the twin monoliths at the center of Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosure D

were

once oriented toward the setting of Deneb in the epoch of their construction, then, as we have seen, a person standing or crouching between them would have been able to view this astronomical spectacle through a holed stone located immediately east of the Vulture Stone. It would have been a similar case in Enclosure C, where the entrant would also have been able to witness the setting of Deneb through the aperture of a holed stone (Pillar 59) when positioned between the twin central pillars.

It is time now to better understand the purpose of these holed stones, focusing our attentions on the example in Enclosure D, which remains in situ. It has carved parallel lines that curve around the hole to form what appear to be naïve renderings of human legs bent at the knee. After coming together beneath the hole the “legs” trail off toward the bottom right-hand corner of the stone, leaving a parallel opening between the knee and the presumed ankles. That the twin sets of parallel lines represent legs, and not something else, is confirmed by the fact that the lower left-hand edge noticeably bulges as if to signify the person’s right-hand buttock (see figure 10.1).

Figure 10.1. Left, decorated holed stone in the north wall of Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosure D. Note the lines flowing around the hole, suggestive of an abstract female form. Right, the broken holed stone in a similar position in Enclosure C.

THE KILISIK STATUE

If the incised lines on the sighting stone do show a pair of legs bent at the knees, then the large hole directly above them can only signify one thing—the person’s, or should I say the woman’s, vulva. A similar hole is seen on the mini T-shaped statue found in 1965 at Kilisik, a village in Adıyaman province, some 46.5 miles (75 kilometers) north-northwest of Göbekli Tepe.

1

In addition to having arms and hands, like the T-shaped pillars at Göbekli Tepe and Nevalı Çori, the statue has an additional line that rises at an angle on both its wide faces to meet the hands on the front narrow face. It seems clear that the figure is lifting up its garment to expose its belly and genitalia (see figure 10.2).

Strangely, the belly or womb area of the statue is sculpted into a much smaller human form represented by a crude head, body, and arms, executed in a style reminiscent of a macabre stone totem pole unearthed at Göbekli Tepe and now in Şanlıurfa’s archaeological museum. This too shows smaller human forms in the position of the womb or stomach of a much larger standing figure (see

plate 24

).

The small figure on the Kilisik statue very likely represents a fetus inside a woman’s womb, the large incised hole immediately beneath the belly emphasizing not just the position of the vulva but also the birth canal. That a very similar, although much larger hole, has been bored through Enclosure D’s potential sighting stone, which is itself surrounded by incised lines arguably signifying the legs of a woman, suggests this hole is also an exaggerated vulva (presumably the holed stone at the same position in Enclosure C played a similar role).

Figure 10.2. Stone statue of a T-shaped figure found in 1965 at Kilisik in Adıyaman province, some 46.5 miles (75 kilometers) from Göbekli Tepe. Note the hole forming the figure’s vulva and the small human figure carved into the stomach area.

This means that when in 9400 BC the setting of Deneb aligned with the hole in the sighting stone in Enclosure D, the star’s presence would have been framed within the abstract woman’s vulva. Clearly, this carefully executed synchronization between star and stone was created to mark the moment of alignment with the opening of the Milky Way’s Great Rift in its role as the suspected entrance to the sky world, where souls departed to in death and, presumably, emerged from at birth. We can go further, for the angle made by the woman’s lower legs, as they trail off toward the right-hand corner of the stone, is similar to the angle of the Milky Way and Great Rift when the star Deneb is at approximately 45 degrees in elevation. In other words, the manner of placement of the woman’s legs seems to emphasize that her vulva marks the entrance to the Great Rift (see figure 10.3).

So if the abstract female form seen on the holed stone in Enclosure D symbolizes the Cosmic Mother, is the purpose of the synchronization between star and stone to indicate that she is about to give birth? Should this surmise prove correct, there can be little doubt that this was a highly symbolic act seen to take place both in a material sense within the womblike enclosure,

and

in a celestial form, with the cosmic child imagined as emerging into life from the opening of the Great Rift (exactly like the rebirth of the solar god One Hunahpu in Mayan myth and legend). In this manner, the cosmic child would have been seen to come forth from Cygnus, then descend the Great Rift to the “ground”; that is, the horizon, where the ecliptic, the sun’s path, crossed the Milky Way in the vicinity of the stars of Sagittarius and Scorpius.

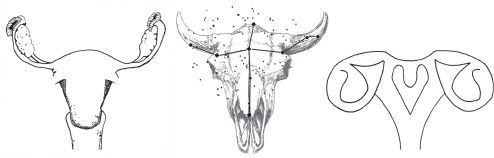

COSMIC BIRTH

Almost exactly what we see represented in abstract form on the sighting stone in Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosure D is found also on the Venus and Sorcerer panel inside France’s Chauvet Cave, which, as we have seen, was created by Upper Paleolithic cave artists some thirty-two thousand years ago. Here too the abstract legs of the “Venus” seem to signify the twin streams of the Milky Way on either side of the Great Rift, with the head of a young bovine overlaid upon the position of the womb (see figure 6.3 below). In this context, the bucranium likely represents the Cygnus constellation in its role as the head of a bull calf, which in prehistoric times was seen as an abstract symbol of the female womb or uterus, complete with its hornlike fallopian tubes (see figure 10.4 on p. 110). The uncanny resemblance between the two is something our ancestors would appear to have realized at a very early stage in human development,

2

making the bucranium, and the bull calf in general, primary symbols of birth and death in the Neolithic age.

Figure 10.3. Göbekli Tepe’s Enclosure D, showing the location of the holed sighting stone in its perimeter wall. Note the Milky Way’s Great Rift on the horizon.

We are reminded also of the 3-D frescoes from Çatal Höyük showing bulls being born from between the legs of divine females (who have the heads of leopards), and the ancient Egyptian belief that the goddess Hathor, in her role as the Milky Way, gave birth each morning to the sun god in the form of a bull calf. The cult of Hathor was virtually synonymous with that of Nut, the sky goddess, who was herself a personification of the Milky Way, her womb and vulva occupied by the stars of Cygnus (see figure 10.5 on p. 110).

3

Nut was the mother of Osiris, the god of death and resurrection, and also of Re, the sun-god, who was reborn each morning from between her loins. In death, the pharaoh would assume the identity of Osiris and reenter the womb of his mother, Nut, in order to reach an afterlife among the stars. In other words, as the resurrected god Osiris the deceased would return from whence he or she had come originally, which was the Milky Way’s Great Rift in the vicinity of the Cygnus constellation.

Figure 10.4. Left, womb or uterus, complete with fallopian tubes. Center, the stars of Cygnus overlaid on a bovine head. Right, an abstract uterus design from the Pazyryk culture of Siberia, from approximately the sixth to third century BC.