God and Mrs Thatcher (26 page)

Read God and Mrs Thatcher Online

Authors: Eliza Filby

By 1983, the number of those in receipt of supplementary benefit – the government’s own poverty measure – was an estimated 8.6 million, which represented a rise of 60 per cent in just four years. But it was the widespread riots during the long summer of 1981 which thrust social deprivation and unemployment into the spotlight. Lord Scarman had been appointed to look into the specific case of Brixton, but as his investigation was restricted to police relations with Britain’s Afro-Caribbean community, it only lightly touched on the underlying tensions such as youth unemployment, which in Brixton was estimated to be over 60 per cent. Archbishop Runcie had seen the raging fires in South London from the tower at Lambeth Palace and at once set to the task of convening a meeting between Brixton’s Christian leaders (who had been crucial in restoring police–community relations) and his

friend from the Guards, Home Secretary Willie Whitelaw. Meanwhile in Toxteth, Liverpool, Bishop David Sheppard and Catholic Archbishop Derek Worlock in a practical move raised the funds for a legal advice centre to address local grievances against the police. Writing in the aftermath of the riots, Worlock confided to one of his colleagues that his was ‘almost the only non-political voice which can be raised at the moment and people appear to be listening’.

27

One who certainly was listening was Margaret Thatcher, who, at Worlock’s suggestion, appointed a minister with special responsibility for Merseyside.

28

In this role, Michael Heseltine would later lean on Worlock and Sheppard for advice as the two religious leaders became crucial brokers in Heseltine’s Merseyside Task Force, designed to regenerate the city.

Some wondered though whether the Church of England could or should be doing more. In May 1981, director of Christian Action and urban priest Eric James wrote a scathing letter to

The Times

in which he accused the Church of ‘retreating to suburbia’ and abandoning those places where it was needed most.

29

A sympathetic David Sheppard convinced Runcie to gather together a group of experts and practitioners to investigate the state of the nation’s cities. In what must have been a calculated move, Runcie also appointed the recently ex-head of the Manpower Services Commission, Sir Richard O’Brien, as its chairman. Following in the well-trodden footsteps of Joseph Rowntree and Charles Booth, the archbishop’s ‘blue-chip’ commission went ‘slumming’, staying in over thirty towns and cities across England over a two-year period. The result,

Faith in the City,

published in December 1985, would prove to be one of the most incisive and important critiques of Thatcher’s Britain. It laid bare, in stark and shocking terms the ‘two nations’ that existed in Britain: that of the ‘shabby streets, neglected houses, sordid demolition sites of the inner city … obscured by the busy shopping precincts of mass consumption’.

30

In heavily politicised sentiments,

Faith in the City

also set out what it considered to be the role of the Church:

It must question all economic philosophies, not least those which, when put into practice, have contributed to the blighting of whole districts, which do not offer the hope of amelioration, and which perpetuate the human misery and despair to which we have referred. The situation requires the Church to question from its own particular standpoint the

morality

of these economic philosophies.

31

In naive hope the commission issued twenty-three policy recommendations to the government, most of which were a rehashing of post-war policies and involved greater public investment. Importantly, the commissioners did not hide behind their closeted walls of piety and were equally scathing of the Church’s own failures. The report called for the establishment of a fund to redirect resources to the inner cities, improved training for urban ministers and a commission for Black Anglican concerns to address the endemic problem of alienated Afro-Caribbean Anglicans in what was to be the first systematic attempt to confront structural racism within the Church. After its decline of the 1960s, the Church of England could have easily retreated into its strongholds in suburbia;

Faith in the City

ensured that the Anglican urban parishes actually underwent a revival over the next thirty years.

To the surprise of the Archbishop of Canterbury, the report caused a stir when it was eventually published, largely because an undisclosed Cabinet member leaked it to the press, slamming it with the inflammatory label of ‘pure Marxist theology’.

32

The revolutionary tag was of course a political tactic to frighten parishioners; it backfired and only resulted in more people actually reading it. The truth was that neither

Faith in the City

nor any other statement by the Church in the 1980s owed any great debt to liberation theology, rather the report drew on what had always been the Church’s default belief in community and communality, which the commission confidently proclaimed were in line with ‘basic Christian principles of justice and compassion’ and shared by ‘the great majority of the people of Britain’.

33

This was a thread of thought whose

lineage could be traced back to William Temple: one that positioned the well-being of the poor as central to national harmony and prosperity.

The commissioners measured the scale of social deprivation not in terms of nutrition or income, as had been the way of Beveridge and Rowntree, but offered a structural and interrelated concept of poverty; one that positioned the underprivileged in the context of the affluent. This was important, not least because Margaret Thatcher consistently denied that ‘primary’ poverty existed in the UK and tended to put such circumstances down to either ‘bad budgeting’ or a ‘personality defect’.

34

The legacy of Tawney’s

Equality

was clearly evident in

Faith in the City

but so too was modern sociological understandings on social exclusion; indeed A. H. Halsey and Ray Pahl, both experts in this field, had served as members of the commission. In the words of commission adviser, Rev. John Atherton,

Faith in the City

was a challenge to Thatcherite individualism and self-help by helping to explain why ‘Etons and Harley Streets will always mean Liverpool 8s and Grunwicks’.

35

Despite this, there was no denying the essentially paternalistic tone of the report with the ‘poor’ the subject of the piece rather than the intended audience: ‘By any standards theirs is a wretched condition which none of us would wish to tolerate for ourselves or to see inflicted on others,’ the commission insisted.

36

There was little sense that the ‘poor’ could be initiators of their own emancipation, although the commissioners thankfully avoided a tone of moralistic condemnation as favoured by their Victorian predecessors. It was, however, easy to dismiss

Faith in the City,

as many did, as yet another episode in the long history of elite spectatorship.

The Labour Party leadership welcomed

Faith in the City

as an opportunity to embarrass the government, but Neil Kinnock was never likely to take policy instruction from the Established Church. Norman Willis, head of the Trade Union Congress, advised all trade union members to read it, although most left-wing activists found the report’s consensual tone too moderate to merit serious consideration. Unsurprisingly, Conservative minister John Gummer dismissed it as misguided, ignorant and

reflective of the Church’s tendency to prioritise societal ills above its true evangelical purpose: ‘[It] is the word of God which the Church of England should be bringing to our God-forsaken inner cities not soggy chunks of stale politics that read as if they have been scavenged from the Socialist Party’s dustbin.’

37

The most positive press review came from the

Financial Times

and interest from City leaders would eventually prompt the Dean of St Paul’s to establish a

Faith in the City

group in which financiers and businessmen were taken on visits to deprived areas. The response from Anglican congregations was inevitably mixed; those who had been slogging away in the inner cities felt a genuine sense of validation while those of a Tory persuasion were distinctly uncomfortable with its anti-Conservative tone. Others objected not to its politics but to the vague theological basis underscoring it. As Frank Field pointedly observed, the report had begun not with an extract from the Bible but a quote from a government White Paper.

Nonetheless,

Faith in the City

’s detailed portrait of a sinking society, descending under the weight of unemployment, social dilapidation and fragmentation was hard to counter or rebuke. It made all Thatcherite talk of ‘get on your bike’ seem frankly out of touch with reality: what about those who did not even have bikes, the report rightly questioned. It challenged the New Right’s critique of dependency culture by juxtaposing the Thatcherite ideal of individual freedom next to the reality: the sense of powerlessness amongst the disenfranchised poor. More pointedly, neo-liberalism was not simply denounced as unworkable or wrong, but morally reprehensible and unchristian.

Faith in the City,

therefore, was important in fuelling the growing public perception of Thatcherism as a doctrine that entirely prioritised profit over human need; a view that particularly rankled Margaret Thatcher.

The Church’s unequivocal opposition was clear, as David Jenkins succinctly put it in 1982: ‘Poverty is morally offensive as well as divinely offensive … it is not one of the unfortunate incidents on the way until we get somewhere else.’

38

Compared to the simplistic protestations by

politicians, the facile slogans of the press and the profit motives of the boardroom, the Established Church appeared to be saying something worthwhile that demanded a response.

Faith in the City

did not provide a political blueprint, but, in the words of Frank Field, it did force ‘the ruling class to consider that even if there was not an alternative, attempts should be made to find one’.

39

The Conservative and Labour parties may have abandoned the values and policies that had defined the post-war settlement, but the Established Church was clearly prepared to mount a defence. Quite why the Church so readily embraced this role can partly be explained by its historic involvement in the formation of the welfare state. This was not simply a distant legacy, but a personal attachment; many of those clergy who assumed the leadership of the Church in the 1980s had developed their faith and political outlook in the era of Butler, Beveridge, Temple and Tawney. Indeed, David Jenkins has stated that hearing William Temple preach at the Royal Albert Hall was one of the defining moments in the formation of his faith. The world of corporatism, full employment, the NHS and the welfare state was not only a political environment in which the Anglican leaders felt comfortable, but one which their forebears had helped create. This was why the Board for Social Responsibility published

Not Just for the Poor: Christian Perspectives on the Welfare State

in 1986, which amounted to a Christian vindication of Beveridge’s original vision. It was also why the Church forcefully opposed the government’s Social Security Act of 1985 on the grounds that it reintroduced Victorian notions of ‘deserving’ and ‘undeserving’ poor that the welfare state had been designed to remove.

In the face of Margaret Thatcher’s ideological onslaught on state welfarism, Anglicans were pushed into reasserting the case – which many believed had been fought and won forty years previously – that a redistributive state was the fairest, most humane and closer to the Christian ideal than the Victorian vision of charity, philanthropy and self-help. The Bishop of Durham certainly framed the battle in

these historical terms. Speaking out against the government’s proposed privatisation of health services in 1989, he questioned: ‘Much has gone wrong, but were the undertaking and intentions in themselves wrong? Was the

message

false, the message, that is, that we as citizens acknowledge together some responsibility for one another?’

40

The bishop christened the NHS, along with state education, social security benefits and pensions, as ‘practical sacraments’, representative, he contended, ‘of the sort of society we desire to be’.

41

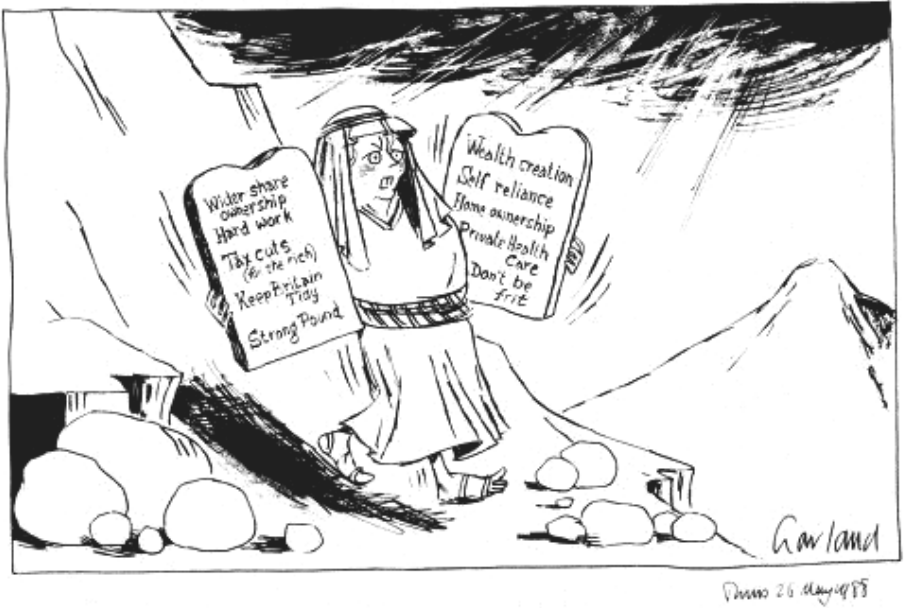

Not all Anglicans were convinced though. Jonathan Redden, a lay Synod member and surgeon from Sheffield, thought the Church’s position not only politically rigid, but theologically unsound in the way that it lauded the NHS and other public services as ‘an extension of the Kingdom of God, whose constitution is written on tablets of stone’.

42

The Church could certainly be accused of peddling an out-of-date consensus and policies. For all its honourable intentions, it could not escape criticisms from both the left and the right that it was predominantly an upper-middle-class institution in both composition and outlook, and that its attitude towards the underprivileged was essentially an age-old paternalistic one. What churchmen called the theology of Christian compassion, Thatcher would dismiss with equal fervour as upper-middle-class guilt.

The Ten Commandments according to Margaret Thatcher. The Church of England is forced into repudiating the Gospel of Thatcherism with their own tablets of stone.