God and Mrs Thatcher (28 page)

Read God and Mrs Thatcher Online

Authors: Eliza Filby

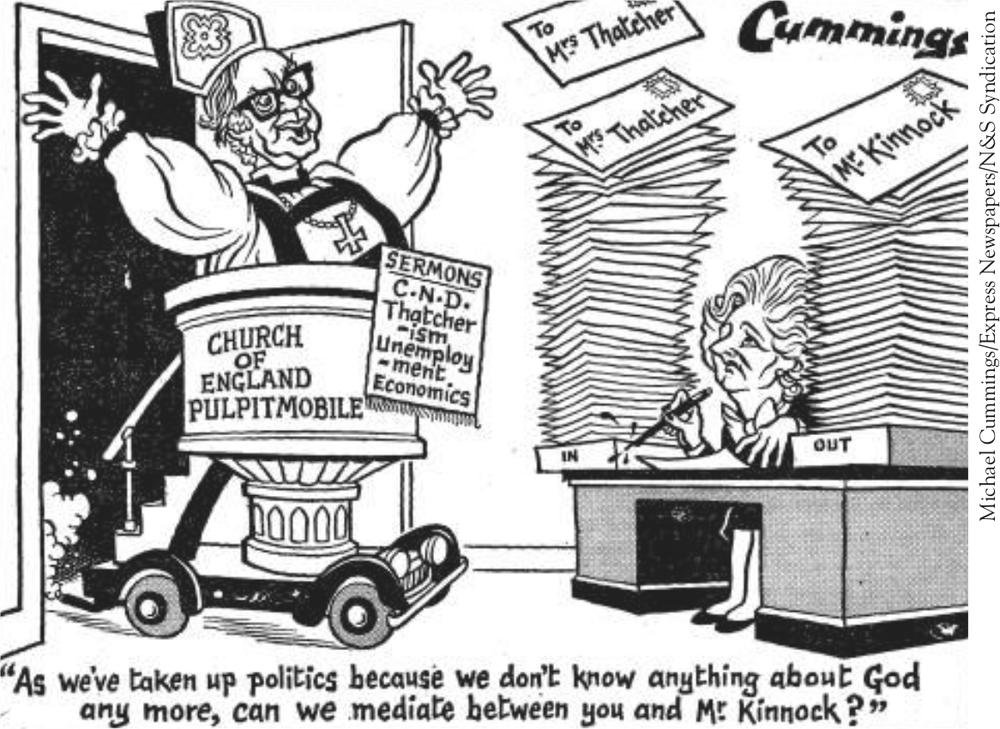

The Church of England in its self-appointed role as political negotiator between the right and the left in Britain

Deputy council leader Derek Hatton later criticised the religious leaders for cowardly siding with the government when the negotiations came to a head. Patrick Jenkin, who had unlike Thatcher been prepared to show some leniency towards the council, was however much more appreciative of Sheppard and Worlock’s position, confiding in a private letter to the Archbishop of Liverpool that ‘the way your clergy and congregations are able to work together should be an inspiration to the politicians, an inspiration to which perhaps too few of us are ready to pay heed’.

63

Jenkin was not the only one to remark on the sharp difference between the ecumenism amongst the churches and the polarities between political parties in this period.

The Church had to wait ten years before it could forge a close

relationship with the Labour Party; in the 1980s however, the Church of England acquired the label of ‘SDP at prayer’. The link was an obvious one for in tone and outlook the Church and SDP shared a great deal in common: both claimed to be inheritors of consensus politics, both projected themselves above class or sectional interests and both promoted a

via media

between the free market and state socialism, which, if the early polls are to be believed, was also in line with the majority of the British public. The fact that the SDP named its think-tank the Tawney Society – much to the ire of Labour activists – indicated a desire on the part of the SDP to fashion itself as the true inheritor of the ethical and progressive tradition in Britain. Its manifesto, with pioneering policies on environmentalism and international aid, obviously appealed to liberal Christians, while the religious bias amongst its leadership was also clearly evident, with Roman Catholic Shirley Williams, Anglican David Owen and Church of Scotland David Steel leading what would later become the SDP-Alliance with the Liberals. Ivor Crewe likened the SDP to a ‘well-heeled suburban church congregation’ who ‘seemed to think that all one had to do to solve the world’s problems was to think the right thoughts and occasionally write out a modest cheque’. This was indeed how a significant number of suburban Anglican congregations thought in the 1980s.

64

Conscious that Christian leaders might prove a useful ally, Shirley Williams approached a number of prelates in 1981 in a hope that they might come out publicly in support of the Council for Social Democracy (the precursor for the SDP). Most prelates declined the invitation, conscious that it would be politically imprudent to do so, although the Bishop of Manchester offered more specific reasons for his refusal. Writing to Williams, the bishop thought that it was ‘too middle class and too intellectual to make a real grassroots appeal’ and rightly predicted that the establishment of a third party would split the anti-Conservative vote. The bishop, though sympathetic to the cause, was unconvinced that it was the answer: ‘I am torn in two on

this one … I agree with you on virtually every point so far … but I still have hopes of a redemption in the Labour party.’

65

‘I completely understand,’ wrote Williams in reply, ‘though I have grave doubts about whether the Labour party can be saved now or indeed whether many people even seriously want to save it.’

66

WHEN THE MINERS

’ Strike was announced in March 1984, the Thatcher government deliberately adopted a hands-free approach, presenting it as an internal dispute between National Coal Board (NCB), led by Ian MacGregor, and Arthur Scargill’s National Union of Mineworkers (NUM). Behind the scenes, of course, the government closely monitored every aspect of the dispute, from the energy stocks to police presence and media management, while trying to incentivise the miners back to work through bonuses as well as the removal of benefits for strikers. Scargill kept an equally close hand on the negotiations although his chronic mismanagement ensured that he lost the support of the TUC, Labour Party and, eventually, his own second-in-command at the NUM, Mick McGahey. Scargill’s catastrophic error of not holding a national ballot reinforced Thatcher’s claims that the unions were inherently undemocratic, while also severely hampering the Labour Party’s support. Nothing revealed the divisions within the labour movement more than the Miners’ Strike; the resilient pits in Yorkshire, Kent, Durham and Scotland held firm while in Nottinghamshire and Derbyshire miners could be seen waving ‘Adolf Scargill’ banners on their way back to work.

Historically, the Church of England could make no claims on the mining areas of Britain but during the strike of 1984–5 it would prove to be one of the few voices of reason amidst a destructive chorus of dogmatism on both sides. The Church of England’s intervention contrasted

with the comparative silence of the Nonconformist churches, once the moral heartbeat of the mining villages. Their relative absence from what was the labour movement’s greatest struggle for a generation was a sure sign that the link between the pit and the chapel was no more. That the decline of Nonconformity directly paralleled the rise of union militancy was symbolised in the figure of Arthur Scargill himself. A product of a Primitive Methodist mother and a communist father, it was political ideology rather than theology that provided men of Scargill’s generation with the answers.

During the strike, the local support from the churches for the miners’ cause varied and was largely dependent on the political views of the incumbent clergy. When a call for funds for mining families was put to the congregations in the village of Easington in Co. Durham, the appeal amassed just £72 from the Methodist chapel and a pitiful £5 from the local Anglican parish. The local Catholic Church raised the most, contributing £711, but this was a tiny sum compared to the funds flooding in from solidarity groups in the south and from abroad. In Durham City, all the local churches ignored letters inviting them to participate in the non-political, non-affiliated charity, the Durham Miners’ Family Aid. Nearby in Coxhoe, it was a similar story, and made all the worse when the local Methodist minister appeared on the radio urging the miners to return to work. Examples such as these could be contrasted with good deeds from individuals such as Anglican Rev. Peter Holland in Seaham, Co. Durham, who opened the doors of his church hall for a soup kitchen and the local women’s support group; after the strike he was given £100 from the group to rewire the church hall.

67

Officials in Church House, London, seized on such efforts, which they considered would be ‘most readily appreciated’ by the public and conveyed ‘the feeling that church leaders are aware of the local pains and problems’. It concluded, rather optimistically, that the Church was now ‘welcomed by people and groups who hitherto would have

had little time for it’.

68

In fact, local demonstrations of Christian solidarity with the miners’ cause had been patchy to say the least.

During the first six months of the strike, ecclesiastical leaders refrained from publicly commenting on the dispute. This policy of enforced silence, however, became increasingly hard to sustain over the summer of 1984, as negotiations reached stalemate, Thatcher cast the striking miners as the ‘enemy within’, and violence erupted at pits between picketers and policemen, most notably and fatally at Orgreave Colliery in South Yorkshire. That September, David Jenkins was elected to the Bishopric of Durham, the fourth highest position in the Church of England, and in a blatant break with ecclesiastical convention, decided to use the occasion of his enthronement ceremony to reflect on the matter most pressing for his diocese: ‘The miners must not be defeated … They are desperate for their communities and this desperation forces them to action.’ Mindful to present the strike as one not about union power or higher wages but the defence of community, Jenkins then referenced the one word missing from both MacGregor’s and Scargill’s vocabulary – compromise – and posited the blame squarely at the government for failing to coordinate a settlement between the NCB and NUM. The only solution, Jenkins proposed, was for the NCB Chairman, Ian MacGregor, whom he incorrectly and clumsily described as an ‘elderly imported American’, to resign.

69

The congregation erupted into a spontaneous applause after Jenkins sat down and the sermon was reprinted in its entirety in the local newspaper the next day. Jenkins’s intervention was a long way from that of his predecessor, Hensley Henson, during the General Strike of 1926. Then the angry pitmen of Durham had tried to throw a man they believed to be the bishop into the River Wear because of the prelate’s vociferous anti-unionist stance. Over the following months, Jenkins met with local union leaders, visited communities and joined in protest marches. For those who had no time for Scargill and had lost all hope of a dignified settlement, Jenkins was a welcome

presence. The bishop followed his sermon with an open letter to Energy Secretary Peter Walker, accusing the government of making a ‘virtue of confrontation’ and demonstrating little understanding of ‘what a community is and what a country is’.

70

Jenkins merely claimed that he was fulfilling his duty of taking the Gospel into the real world but his trenchant words riled the government: ‘The Bishop of Durham is plain Mr Jenkins when he gives me his political views’ preached John Gummer (then Chairman of the Conservative Party) from the pulpit of the University Church in Cambridge that November.

71

Peter Walker tried a different tack responding in a public letter not with anger but a hint of mockery: ‘I was surprised to hear that in a Christian’s view there was something wrong with being elderly or American. And I hope all Christians will look very carefully at those who organise mob violence.’

72

Jenkins’s intervention had the effect of propelling a reluctant Church into the centre of the conflict as journalists stationed themselves outside Auckland Castle, ready for the bishop’s next uncensored statement. Robert Runcie, who was reportedly appalled by Jenkins’s tone, hastily issued a letter of apology to MacGregor on his bishop’s behalf. But Runcie too let it be known that he considered Jenkins’ intervention a legitimate act of Christian prophecy: ‘You can no more preach in Durham without mentioning the miners’ strike that you can preach in South Africa without reference to Apartheid,’ said Bishop Ronald Gordon, head of Runcie’s personal staff.

73

A week later the Archbishop of Canterbury was pictured visiting the Creswell colliery near Derbyshire and in a sermon in Derby Cathedral, using carefully chosen words, Runcie reiterated Jenkins’s call for a settlement while also resolutely condemning the violence at the picket lines. For Runcie, it was not a question of engaging with the intricacies of the dispute but offering some pertinent words on the damaging ramifications for the body politic. As he later explained in an interview with

The Times,

published on the eve of the Conservative Party conference, it was the ‘abuse,

the cheap imputation of the worst possible motives, treating people as scum in speech, all this pumping vituperation’, which had escalated the industrial dispute into violence.

74

Here Runcie was clearly passing comment on Thatcher’s denigration of the miners as the ‘enemy within’, while also using the government’s handling of the strike as an illustration of its values; namely the prizing of economic efficiency over social harmony. Neil Kinnock, mindful to distance himself from Scargill and the violence at the pits, had taken a similar line, but his hands were tied in a way that the archbishop’s were not. In a battle in which there was apparently no middle ground, the Church was inevitably positioned as siding with the unions.

The Economist

wryly mooted that this was possibly because churchmen could sympathise with an institution that was also suffering from a depleting membership. Some even made the pertinent point that the Church’s systematic closure of parishes was much like MacGregor’s planned reorganisation of the mining industry: Anglicanism, like coal, was yet another nationalised industry going to the dogs.

The Church’s position, however, was a classic and instinctive Anglican reassertion of the centre ground, much like Archbishop Randall Davidson’s botched intervention in 1926. This was the doctrine of ‘keeping everyone on board’, softening animosities between warring factions, particularly classes. With Thatcher content to allow the undemocratic intransigency of the NUM to dominate the legitimacy of the strike, it was the Church which broadened the discussion to what was really at stake; the impact of deindustrialisation on communities. This may have been out of Anglican distaste for extremity rather than genuine solidarity or expertise, but, as Jenkins explained in his enthronement sermon, this concept had a sound biblical basis. ‘Mutually worked out compromise is the essence both of true godliness and of true humanity. Anyone who rejects compromise as a matter of policy, programme or conviction is putting himself or herself in the place of God.’

75

Here Jenkins was not only dismissing the conviction

politics of the right and left but also making an explicit link between consensual political values and liberal Christianity. As if to reinforce his point, Jenkins added: ‘We have no right to expect a church which will guarantee us infallible comfort’ or ‘a Bible which will assure us of certain truth’.

76

Politics, like theology, he pertained, should not be based on uncompromising dogma but on continual negotiation. This was the liberal basis of his faith, hence his questioning of the historical validity of the Bible, and also at the root of his politics.