God and Mrs Thatcher (5 page)

Read God and Mrs Thatcher Online

Authors: Eliza Filby

A copy of Margaret Thatcher's childhood catechism kept in her personal archives at Churchill College, Cambridge reveals the type of religious instruction she received. The catechism (a Greek word literally meaning âindoctrination') was conceived as a spiritual âQ&A' covering redemption, sin and judgement as well as the Ten Commandments, Beatitudes, Lord's Prayer and the Apostles' Creed. Margaret Roberts's copy is heavily annotated but there are no signs of boredom: no doodles or boys' names encased within a heart and arrow, only the markings of an attentive and serious scholar. The young Margaret seems to have been extremely taken with the notion of sin and service, which she underlined at several points: âWhat is sin?' âSin is disobedience to the will of our heavenly father in

thought

, word or deed.' This was a Methodist instruction, which principally stressed the individual relationship with God, the Christian notion of service and the all-encompassing nature of sin.

25

The Sunday service at Finkin Street Church would follow the standard form of six hymns alternated with prayers and lessons before climaxing with the preacher's sermon. Most of the children of the congregation

were spared the sermon, sneaking out before its commencement, but the Roberts sisters were made to dutifully listen. Margaret Thatcher later recounted how she and Muriel used to impatiently time the preacher and would get agitated if the sermon went over fifteen minutes. Afterwards, it was common for the speaker to be invited to supper by one of the congregation, with Alfred Roberts, lay-preacher and local grandee, often willing to step in as host.

Alfred Roberts was given his first taste of leadership at Finkin Street Church, serving on both the Leaders' and Trustee boards. It was here, sitting round a table discussing age-old problems such as the appalling state of the lavatories, that Alfred Roberts learnt the tedious art of governance by committee. The minutes reveal a preoccupation with declining membership particularly in the weekly Bible-study classes which, in 1928, had an average of thirty-two but by 1946 had decreased to just seven: a downwards slide that was never halted. It was customary for all churches to administer a poor fund for destitute members of the congregation and records reveal that a Mrs Wright, whose husband was seriously ill and could not work, was deemed deserving and was regularly sent one pound throughout the 1920s. Chapel finances remained the chief worry, and, as chairman of the Circuit Finance Committee, something with which Alfred Roberts was intimately involved. Account books for Finkin Street reveal that it was seriously in debt, sinking under the weight of two-pound per week interest payments to Midland Bank; a situation that was only resolved when the Wesleyan Conference agreed to step in. Thrift was not always practised as much as it was preached, it seems. One contemporary accused Finkin Street of offering âcheery chats for weary wives' while the ministers shamelessly profited from their flock.

26

There is no evidence of any wrongdoing in the archives; the truth was that the building was nearly a century old and substantial funds were required to maintain it.

Finkin Street Church is an imposing stone building, situated down an intimate side street of Georgian houses. Until 2013 it had been

registered for sale but the only potential buyer â a chain of Italian pizzerias â had been forced to pull out once it was realised that the interiors were protected under its Grade II-listed status. It is still used by a small congregation of Grantham's (now amalgamated) Free Churches but in a building with a capacity of 600 that takes ten hours to heat in the winter, it is ill-suited to the contemporary demands of this small, dedicated congregation. The church may have escaped the common fate of commercialisation that has befallen many former places of worship in Britain, but preservation has not helped its cause. Unlike other recycled sites of Britain's industrial landscape â the factories converted into gentrified apartments, the quarries buried under new shopping complexes, the redundant chapels transformed into mosques â Finkin Street Church remains a shell to Britain's lost Nonconformist age.

Finkin Street, c. 1920. âWesleyan Chapel' is carved in stone on its exterior

Built in the Tuscan style of the 1840s, Finkin Street's denominational tradition is proudly carved in stone on its exterior. Inside, the layout looks much like a civic chamber with its semi-circular two-tiered

auditorium. Closer inspection reveals it to be a spatial representation of the âpriesthood of believers', with no altar dividing the shepherd and his sheep. All eyes are directed towards the organ for the hymnody and the elevated pulpit, which is situated in the middle rather than to the side. Most churches tended to have two separate (often encased) pulpits, one for the ordained, another for the laity. Finkin Street is testimony to the spirit of egalitarianism in Methodism, with its singular stand.

Inside Finkin Street. All eyes are focused on the pulpit and the organ for the source of Methodist worship: the sermon and the hymnody

At Finkin Street, sermon duty would alternate between the chapel minister, local circuit preachers and, as its records reveal, even visiting speakers from distant parts of the empire, including Australia, West Africa and Hong Kong. In 1918, the same year that women were granted the vote, Wesleyan Methodists lifted the ban on female preachers. Several women officiated at Finkin Street, particularly in wartime, although there is no evidence that Margaret Thatcher's mother, the ever-practical, ever-in-the-background Beatrice, ever took the plunge. Watching would have

been the young Margaret Roberts, probably fidgeting on the hard uncomfortable wooden pews with her legs impatiently swinging to and fro as the sermon reached beyond the reasonable quarter of an hour. In her memoirs, Thatcher recounts how those Sunday sermons left a lasting impression, particularly one on Christian charity and illegitimacy, and a wartime sermon linking the fighter pilots of the Battle of Britain with the Apostles and another on God's providence. By far the most inspiring figure in the pulpit, however, must have been her father. Standing at over 6 ft tall with his shock of white albino hair and in Thatcher's own description, affected âsermon voice', one would imagine that Alfred Roberts assumed the air and authority of an Old Testament prophet. Margaret Thatcher later remarked that he was a âpowerful preacher' whose sermons were full of âintellectual substance'.

27

It was certainly true that Roberts was a famed local preacher who would tour the local chapels it is said, often with his youngest daughter in tow. A circuit calendar from 1944 shows that Roberts preached at least four times a month in different locations, at both afternoon and evening services.

Lay-preachers were not simply foot soldiers, but esteemed officers, particularly those gifted with a rhetorical flair and an ability to rouse the troops. They were required to undergo some training and would be responsible not just for the sermon, but the entire service. For a man like Alfred Roberts, who had left school at an early age, it is quite possible that this tutelage, and the respect he gained from preaching in various pulpits across Lincolnshire, stirred a sense of self-belief that fuelled his political ambitions. Methodists sought to stir the individual's imagination through the sermon in the hope of leading the flock to a deeper, more conscious faith. As far as we know, Alfred Roberts did not partake in open-air preaching; religion, like politics, had gone âinside' by the inter-war years. His sermons therefore would have been delivered within the confines of a chapel and preached to the faithful. Yet this was no easy mission. Roberts had the unenviable task of keeping the laity âconverted' at a time when many were drifting away.

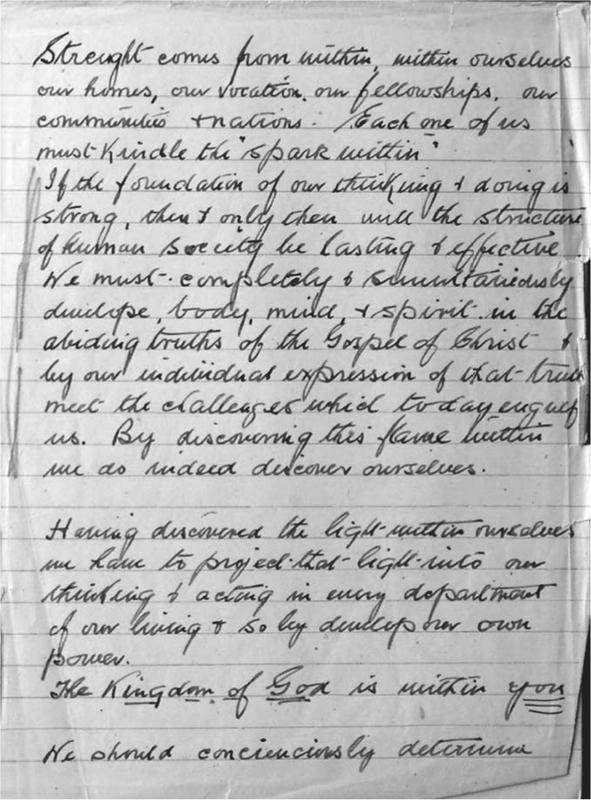

But if we have the image of Alfred Roberts in the pulpit, what of his words? A collection of his sermon notes, kept by Margaret Thatcher and now housed in her personal archive, serve as a fertile source into the mind and manner of a man to whom so much has been attributed, but so little is known. Mostly dating between 1941 and 1945, these handwritten notes were jotted down at the back of his daughter's chemistry book, possibly due to the paper shortage during the war. They reveal an impassioned man at work, with some parts illegible with frequent crosses out, underlining, capital letters for emphasis as well as bullet points to be hammered home to the flock.

âThe Kingdom of God is within you': Alfred Roberts's sermon notes c. 1940

Like a musical score, the underlying aspect here is the rhythm of the preacher's delivery: all staccato sentences, repetition of phrases, a built crescendo followed by exaltation. But there is little appreciation of language for its own sake: no flowery semantics, just simple words of faith.

28

As would be expected, the notes contain the essential ingredients of

the dissenting tradition: individual salvation (âThe Kingdom of God is within you!') and the Protestant work ethic (âIt is the responsibility of man ordained by the creator that he shall labour for the means of existence. It is a supreme act of faith.'). âYou possess all you need,' Alfred Roberts insisted. âThere is nothing to acquire. Learn to recognise what is already yours.' All that was necessary was hard work, for âa lazy man' was one who had âlost his soul already'.

Roberts would remind his audience why they were not Roman Catholics, evoking Martin Luther's edict âindividual salvation by faith alone' and also why they were not Anglicans, judging that a church âunder the tutelage of Kings and Princes' was merely a temporal vehicle hosed in holy water. Alfred Roberts, however, appreciated the nature of Christian unity: the âdiversity of administration but the same Spirit and Lord.' Above all, Christianity in Roberts' view concerned free will, a spiritual inwardness and an individual Covenant with God. Roberts was not rigid and prescriptive but intellectually curious when it came to his faith. As historian Antonio Weiss has highlighted, references to Alexander Pope and William Wordsworth in the sermon notes reveal a man who was âun-Piestistic' who liked to be challenged by secular thought.

29

Contained here are also instructions to prospective preachers, with Roberts setting out the requirements necessary to lead and inspire a following. First, it demanded absolute conviction: ââ¦[in order to] kindle the flame in the heart of your hearer, you will have to keep the flame burning on your own altar.' Secondly, he was cautious that it would be a slog: âYour task demands and deserves sheer hard work. Sweat of brains and discipline of soul ⦠[if] you desire your sermon to make a difference to human lives and lead them more thoroughly to surrender to the sovereignty of Christ.' Finally, he recognised the importance of being at one with the flock: âNever allow yourself to become aloof and out of touch with the realities of other men's lives.' Thatcher never made any direct reference to these guidelines even though she often quoted other pieces of advice given to her by her father. And yet these

qualities can be readily associated with her leadership. There is little doubt too that Margaret Thatcher self-consciously embraced the style and tone of a preacher. As she told interviewer Brian Walden in 1983: âThere would have been no great prophets, no great philosophers in life, no great things to follow, if those who propounded the views had gone out and said “Brothers, follow me, I believe in consensus.” No, Brian, no.'