God and Mrs Thatcher (6 page)

Read God and Mrs Thatcher Online

Authors: Eliza Filby

Politics, according to Margaret Thatcher, was about conviction: an understanding which she had been taught âin a small town by a father who had a conviction approach'.

30

Examining her father's sermon notes, there is little reason to doubt her on this point.

Historically, Methodism always applied itself more readily to politics than Anglicanism. The Established Church was tied too closely to the state to question it. Unsurprisingly, there is clear evidence of a fusion between the temporal and spiritual in Roberts's sermons. In a coded reference to the leading debate of inter-war politics â protectionism versus free trade â Roberts let slip where he stood on the matter: âGod refuses to put grace on a tariff' with the implication being that the universal freedom of market mirrored the universal availability of grace. This was a doctrinal legitimation of the âinvisible hand', which echoed that of nineteenth-century free trade Liberals and one that his daughter would annunciate with equal passion forty years later.

As would be expected of a dissenter, Alfred Roberts also extolled the virtues of religious liberty and condemned its opposite: religious uniformity. But this too was laced in political terms, with religious conformism likened to âa denominational closed shop', thereby betraying a belief that compulsory trade union membership and mandatory affiliation to a particular faith were both infringements on personal freedom. In another extract, Alfred Roberts aligned spiritual conformity to totalitarianism: âUniformity can be a soul destroying agent, as evil as totalitarianism, and totalitarianism, can end in the

systematic dehumanisation of man.' Addressing the party-faithful at the annual conference in 1989, Thatcher served up a similar homily on individual liberty in reference to her ideological battle against communism: âRemove man's freedom and you dwarf the individual, you devalue his conscience and you demoralise him.'

31

There is an indication though that her father, in line with other men of his generation, acknowledged the social evils of the age. In a clear reference to the Beveridge Report, published in 1942, Roberts preached that âignorance, squalor, hunger and want, injustice and oppression' was a âbetrayal of our Lord and Master'.

32

Yet, in another sermon from 1950, five years into Attlee's Labour government, he offered a coded warning to those who invested too much faith in temporal power: âMen, nations, races or any particular generation cannot be saved by ordinances, power, legislation. We worry about all this, and our faith becomes weak and faltering.' Roberts also revealed himself to be sceptical when it came to the Church's involvement in social affairs. Going against the then consensus within Methodism, Roberts thought âsocial issues' a diversion, which turned the church into âa glorified discussion group'. Margaret Thatcher would make a similar point in a speech to the General Assembly of the Church of Scotland in 1988: âChristianity is about spiritual redemption, not social reform.'

33

In her father's view, the real danger in the modern world was not poverty but affluence. âNo man's soul can be satisfied with a materialistic philosophy' only âthe stern discipline and satisfaction of a spiritual life'. The struggle of how to morally square the free market with the materialist culture it inspired was something his daughter would struggle with throughout her premiership.

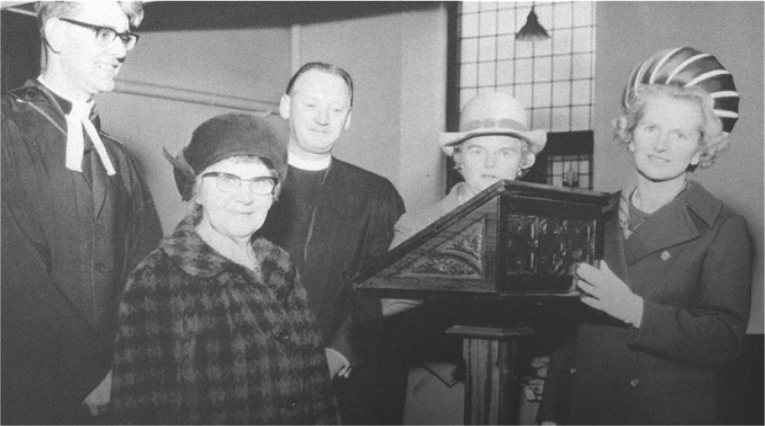

In Finkin Street Church, to the right of the pulpit, there stands a lectern with a small plaque honouring Alfred Roberts's service to both the church and community placed there following his death in 1970. It is apt that the only mark of remembrance to Alfred Roberts in Grantham is here in Finkin Street Church and in the form of a lectern.

Margaret Thatcher obviously thought so too, making a rare trip to Grantham for the commemoration.

A brief return to Grantham: Margaret Thatcher posing with her step-mother, Cissie Roberts (left) and sister, Muriel (middle), for her father's commemorative lectern at Finkin Street Church

ALFRED ROBERTS MAY

have been a prominent lay-preacher but he clearly felt his calling was in civic rather than religious life. He was not unique in this respect. Methodist lay-preachers tended to have the public-speaking skills and the networks necessary for politics; the Salem chapel in Halifax, for example, was known locally as the âMayor's nest' because it was the source of so many mayors in the town.

In her memoirs, Margaret Thatcher described her father as an âold-fashioned Liberal'.

34

Alfred Roberts had certainly supported the party in his youth, had endorsed the National Government in the 1930s (with which many Liberals were aligned) but later came out as a Conservative. He publicly declared his conversion in 1949 at his daughter's adoption meeting for her parliamentary candidature for the Dartford constituency. On this occasion, according to press reports, Roberts claimed that the Conservative Party âstood for very much the same things as the Liberal Party did in his young days.'

35

In Alfred Roberts's political journey we find one of the important shifts in twentieth-century British politics: the movement of lower-middle-class Nonconformists from the Liberals to the Conservatives.

Historically, the Nonconformist vote had overwhelmingly but not

exclusively gone to the Liberal Party, yet this affiliation, while strong amongst Primitive Methodists, Baptists, Congregationalists and Unitarians, was decidedly less so amongst the Wesleyans, who in fact had been Tories until the mid-nineteenth century and remained distrustful of the Liberal Party's irreligious and radical tendencies.

*

Wesleyans continued to be ambivalent about their religious association with other Nonconformists and the political connection with the Liberals. Liberal Nonconformity, as a political force, suffered its first major blow in 1886, when Gladstone's dogged fight for Home Rule in Ireland prompted seventy-eight Liberal MPs led by Nonconformist Joseph Chamberlain to enter into an alliance with the Conservatives as Liberal Unionists. Liberal Nonconformity did, however, enjoy a brief revival in the Edwardian period â chiefly during a fight over denominational education and at the 1906 election â but the drift of the dissenters into separate Conservative and Labour camps had already begun and by the eve of the Second World War this realignment would be practically complete.

The influence of Nonconformity was, of course, evident in the formation of the trade union movement and later the political party with Labour's first leader, Keir Hardie, promoting âLabour and Liquor don't mix' as one of his key electoral slogans. The decline of the Liberal Party in the 1920s prompted a second wave of converts to the socialist cause. One such MP was Anthony Wedgwood Benn's father, William, who defected in 1927. Indeed many future Labour stars, such as Anthony Wedgwood Benn and Michael Foot were of Liberal Nonconformist ancestry. Michael Foot's father, Isaac, for example, had been a Methodist and Liberal MP in the West Country between 1922 and 1935 where he led campaigns against drinking and betting.

Thatcher, too, had a Liberal-voting father but he represented a different phenomenon. Alfred Roberts, born in 1892, would have cast his first vote in the âcoupon election' of 1918, held after the First World War and

the passing of the Representation of the People Act, which had removed all property restrictions on voters. One would have imagined that Roberts would have put an âX' for Lloyd George's coalition, the eventual victors, but possibly for the last time. The Liberal Party was already in decline and soon internal factionalism and competing forces would see it collapse as a ruling electoral force. The Nonconformist vote, already fragmented, split irrevocably as the Labour Party shored up the working-class constituencies while the Conservative Party made successful appeals to wavering Liberal voters, chiefly Wesleyans. Paradoxically, just as the various factions within Methodism unified in 1932, so the political divisions within it were more exposed than ever before.

Over time the electoral map of Britain transformed as urban and industrial areas turned from Liberal to Labour, and the new suburbs, small towns and rural areas turned Tory blue. But this was far from systematic. In areas such as Cornwall and parts of Wales, the Liberal allegiance held firm even after Nonconformity itself collapsed. It was, above all, a gradual and patchy development, shaped as much by local tensions (Grantham for example shifted between Conservative, Liberal and Independent in these years) as it was by a chaotic national scene which saw two coalitions, a National Government, the entry of women into the political sphere and the largest extension of the franchise in British parliamentary history. For these reasons, it was not until after the Second World War that the dust settled on these new partisan allegiances, but the after-effects of the Liberal Party's decline would be felt right up to the 1980s.

Some within the Conservative and Unionist Party understandably greeted the extension of the franchise in 1918 with paranoia, but party managers soon realised that capturing floating Liberal voters would be crucial in order to counter Labour's natural advantage. This they proved remarkably effective in doing: its proportion of the vote never fell below 38 per cent while it managed to hold office (either in coalition or as a single party) twenty-five out of the twenty-nine years between 1916 and 1945. That the Conservative and Unionist Party was able to seize the initiative

was largely due to the unassuming but canny leader Stanley Baldwin, in charge from 1923â37. Baldwin saw his mission as refashioning Conservatism for the mass democratic age, which involved targeting potential voters like Alderman Roberts. Even though Baldwin was a practising Anglican, he was of Wesleyan heritage; a fact he never ceased to remind Nonconformist audiences. Baldwin addressed more Free Church gatherings than any Tory before him where he would promote his party âas the natural haven of rest' for the âindependent and sturdy individualism' of Nonconformists.

36

During the 1929 election, Baldwin's schmoozing of Nonconformists even prompted the Anglican

Church Times

to remark somewhat bitterly that the Conservatives âshow themselves far more eager to gain sympathy from Nonconformists than from Church-people'.

37

At the 1931 election, most of the Free Church press came out in support of the National Government. The result was a landslide for the Conservative and Unionist Party and, while some Liberals served in the Cabinet as part of the National Government, factionalism within the party would in the long run ensure that it would no longer be the dominant party at Westminster. Baldwin excelled in converting a crucial band of Nonconformists in much the same way that Margaret Thatcher would later successfully appeal to âupwardly mobile' floating voters in the 1980s. This shift was to be a lasting change. Recent converts felt reassured by Baldwin's successor, Birmingham Unitarian and Liberal Unionist Neville Chamberlain, and later Winston Churchill, who, although in character was the complete antithesis to the Nonconformist conscience, he nonetheless had been a Liberal before crossing the floor in 1924.

It was for these reasons, then, that Alfred Roberts switched his allegiance to the Conservatives and why in 1935 he, along with his youngest daughter, campaigned for the National Government Conservative candidate, the Eton-educated, ex-military officer Sir Victor Warrender for the constituency of Grantham and Rutland. On polling day, the ten-year-old Margaret acted as the runner, relaying information to the committee room in Lord Brownlow's Belton House; it was to be her first taste of politics. Margaret Thatcher was every inch a true-blue, but her political heritage

was Nonconformist Liberalism. Even in the 1950s, the heterogeneous mix of Liberals and Conservatives within the Conservative and Unionist Party was still clearly evident, although it had now firmly established itself not in terms of religion but in ethos. There was deep division between libertarians and paternalists. The paternalists would have their run of it during the 1950s and 1960s; Margaret Thatcher's ascent in 1975 would symbolise the eventual victory of the libertarian strand within the party.

Stanley Baldwin's other great ability was to stir up bourgeois and non-unionised working-class fears about socialism, which was particularly virulent amongst men like Alfred Roberts, whose paranoia stemmed more from domestic and parochial concerns than events in Moscow. The English petite bourgeoisie now defined themselves not against the landed Tory squires, but the unionised working class. Nothing, therefore, did more to alienate them from the Liberal Party than when Lord Asquith, with the agreement of Lloyd George, allowed the Labour Party to govern for the first time in 1924. And nothing did more to further endear them to the Conservatives than when, two years later, the Baldwin government crushed the General Strikers in 1926.