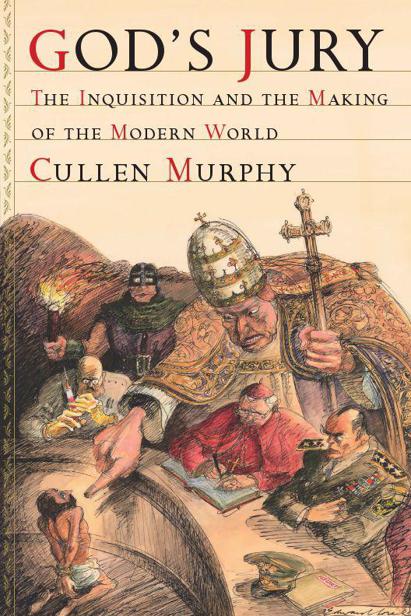

God's Jury: The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World

Read God's Jury: The Inquisition and the Making of the Modern World Online

Authors: Cullen Murphy

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #History, #Research, #Society, #Religion

1. Standard Operating Procedure

Copyright © 2012 by Cullen Murphy

All rights reserved

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this

book, write to Permissions, Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing

Company, 215 Park Avenue South, New York, New York 10003.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Murphy, Cullen.

God’s jury : the Inquisition and the making of the modern world / Cullen Murphy.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN

978-0-618-09156-0

1. Inquisition. I. Title.

BX

1713.

M

87 2012

272'.2—dc23

2011028599

Book design by Brian Moore

Printed in the United States of America

DOC

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

1. Standard Operating ProcedureFor A.M.T.

The Paper Trail

No one goes in and nothing comes out.

—

A VATICAN ARCHIVIST,

1877

Theology, sir, is a fortress; no crack

in a fortress may be accounted small.

—

REVEREND HALE, THE CRUCIBLE, 1953

The Palace

O

N A HOT FALL

day in Rome not long ago, I crossed the vast expanse of St. Peter’s Square, paused momentarily in the shade beneath a curving flank of Bernini’s colonnade, and continued a little way beyond to a Swiss Guard standing impassively at a wrought-iron gate, the Porta Cavalleggeri. He examined my credentials, handed them back, and saluted smartly. I hadn’t expected the grand gesture, and almost returned the salute instinctively, but then realized it was intended for a cardinal waddling into the Vatican from behind me.

Just inside the gate, at Piazza del Sant’Uffizio 11, stands a Renaissance palazzo with the ruddy ocher-and-cream complexion of so many buildings in the city. This is the headquarters of the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith, whose job, in the words of the Apostolic Constitution,

Pastor bonus,

promulgated in 1988 by Pope John Paul II, is “to promote and safeguard the doctrine on faith and morals throughout the Catholic world.”

Pastor bonus

goes on: “For this reason, everything which in any way touches such matter falls within its competence.”

It is an expansive charge. The CDF is one of nine Vatican congregations that together make up the administrative apparatus of the Holy See, but it dominates all the others. Every significant document or decision emanating from anywhere inside the Vatican must get a sign-off from the CDF.

The Congregation also generates plenty of rulings of its own. The Vatican’s pronouncements during the past decade in opposition to cloning and same-sex marriage originated in the CDF. So did the directive ordering Catholic parishes not to give the names of past or present congregants to the Genealogical Society of Utah, a move that reflects the Vatican’s “grave reservations” about the Mormon practice of posthumous baptism. The declaration

Dominus Jesus,

issued in 2000, which reiterated that the Catholic Church is the only true church of Christ and the only assured means of salvation, is a CDF document.

Because the Congregation is responsible for clerical discipline, its actions—and inactions—are central to the pedophilia scandals that have shaken the Catholic Church. For more than two decades, the Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith was headed by Cardinal Josef Ratzinger, now Pope Benedict XVI, who during his long reign as prefect was known as the enforcer and sometimes as the

Panzerkardinal

—bane of liberals, scourge of dissidents, and bulwark of orthodoxy narrowly construed. The Congregation has been around for a very long time, although until the Second Vatican Council it was called something else: the Congregation of the Holy Office. From the lips of old Vatican hands and Church functionaries everywhere, one still hears shorthand references to “the Holy Office,” much as one hears “Whitehall,” “Foggy Bottom,” or “the Kremlin.”

But before the Congregation became the Holy Office, it went by yet another name: as late as 1908, it was known as the Sacred Congregation of the Holy Roman and Universal Inquisition. Lenny Bruce once joked that there was only one “

the

Church.” The Sacred Congregation of the Universal Inquisition was the headquarters of

the

Inquisition—the centuries-long effort by the Church to deal with its perceived enemies, within and without, by whatever means necessary, including some very brutal ones. For understandable reasons, no one at the Vatican these days refers to the Congregation as “the Inquisition” except ironically. The members of the papal curia are famously tone-deaf when it comes to public relations—these are men who in recent years have invited a Holocaust-denying bishop to return to the Church,

have tried to persuade Africans that the use of condoms will make the AIDS crisis worse,

and have told the indigenous peoples of Latin America that their religious beliefs are “a step backward”

—but even the curia came to appreciate that the term had outlived its usefulness, although it took a few centuries.

It’s easy to change a name, not so easy to engage in genetic engineering (which the Church would not encourage in any case). The CDF grew organically out of the Inquisition, and the modern office cannot escape the imprint. Ratzinger, when he was still a cardinal, was sometimes referred to as the grand inquisitor. New York’s John Cardinal O’Connor once introduced the visiting Ratzinger that way from a pulpit in Manhattan—a not entirely successful way to break the ice.

The epithet may have originated in “the fevered minds of some progressive Catholics,” as a Ratzinger fan site on the Web explains, but it became widespread nonetheless. (In response to a Frequently Asked Question, the same site offers: “Good grief.

No, Virginia, Cardinal Ratzinger was not a Nazi.

”)

The palazzo that today houses the Congregation was originally built to lodge the Inquisition when the papacy, in 1542, amid the onslaught of Protestantism and other forms of heresy, decided that the Church’s intermittent and far-flung inquisitorial investigations, which had commenced during the Middle Ages, needed to be brought under some sort of centralized control—a spiritual Department of Homeland Security, as it were. Pope Paul III considered this task so urgent that for several years construction on the basilica of St. Peter’s was suspended and the laborers diverted, so that work could be completed on the palace of the Inquisition.

At one time the palazzo held not only clerical offices but also prison cells. Giordano Bruno, the philosopher and cosmologist, was confined for a period in this building, before being burned at the stake in Rome’s Campo dei Fiori, in 1600.

When I first set foot in the palazzo, a decade ago, it was somewhat shabby and ramshackle, like so much of Rome and, indeed, like more of the Vatican than one might imagine.

Outside,Vespas tilted against kickstands. In a hallway beyond the courtyard, a hand-lettered sign pointed the way to an espresso machine. A telephone on the wall dated to the 1950s. Here and there, paint flaked from ceilings and furniture. But the Congregation has a Web site now, and e-mail, and a message from Piazza del Sant’Uffizio 11 can still fray nerves in theology departments and diocesan chanceries around the world.

The Congregation for the Doctrine of the Faith inherited more than the Inquisition’s institutional DNA and its place on the organizational charts. It also inherited much of the paper trail. The bulk of the Vatican’s records are part of the so-called Archivio Segreto, and for the most part are stored in a vast underground bunker below a former observatory.

(

Segreto,

though translated as “secret,” carries the connotation “private” or “personal” rather than “classified.”) But the Vatican’s holdings are so great—the indexes alone fill 35,000 volumes—that many records must be squirreled away elsewhere. The Inquisition records are kept mainly in the Palazzo del Sant’Uffizio itself, and for four and a half centuries—up until 1998—that archive was closed to outsiders.

At the time of my first visit, the Inquisition archive—officially, the Archivio della Congregazione per la Dottrina della Fede—spilled from room to room and floor to floor in the palazzo’s western wing, filling about twenty rooms in all. It was under twenty-four-hour papal surveillance, watched over by a marble bust of Pius XII, a stern and enigmatic pontiff and now a candidate for sainthood, despite his troubling record in the face of the Holocaust. Pius was assisted in his duties by the sixteenth-century cardinal-inquisitor and papal censor Robert Bellarmine, whose portrait dominated a nearby wall, larger in oil than he was in life. The rooms were bathed in a soft yellow light. A spiral staircase connected upper and lower levels. Dark bookshelves stood in tight rows, sagging under thick bundles of documents. Many were tied up with string in vellum wrappers, like so much laundry. Others were bound as books. The spines displayed Latin notations in an elegant antique hand. Some indicated subject matter: “

De Spiritismo,

” “

De Hypnotismo,

” “

De Magnetismo Animale.

” Most were something else entirely. They contained the records of individual cases and also the minutes of the Inquisition’s thrice-weekly meetings going back half a millennium. The meetings were held on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays, and the pope himself presided once a week.

The cataloguing is by modern standards haphazard, even chaotic, reflecting centuries of handling and the peculiar organizational psychology of the Holy See. As one scholar has noted, the Vatican archives were arranged in a way that made sense for the curia, not for the convenience of modern historians.

Pull down a bundle and you may stumble on internal deliberations over the censorship of René Descartes. Pull down another and you may discover some Renaissance cardinal-inquisitor’s personal papers: the original handwritten records of all his investigations, chronologically arranged; a bureaucratic autobiography—he was proud of what he had achieved—with reflective comments scrawled in the margins; and here and there a small black cross indicating that a sentence had been duly carried out. Pull down a third bundle and you may find an account of a routine meeting, the sudden insertion here and there of several black dots by the notary indicating that the inquisitors had gone into executive session and the notary had been dismissed from the room—a more reliable procedure than the modern practice, employed by intelligence and law-enforcement agencies, of “redacting” a sensitive document with heavy black bars. No court order or Freedom of Information Act can unlock what the black dots conceal.

The atmosphere in the reading room is one of warmth and stillness. Hints of slowly crumbling leather hang in the air. A few scholars sit at tables. No one talks:

silentio

is the explicit rule. Espresso must be left outside. Smoking is prohibited. The physical experience is that afforded by any ancient library, enfolding and reassuring—which serves only to heighten a sense of psychic disconnection. When the Archivio was first opened, a Vatican official, Cardinal Achille Silvestrini, expressed the hope that it might contain “some pleasant surprises.”

But the record preserved on the millions of pages in these rooms is mainly grim: a record of lives disrupted and sometimes summarily put to an end; of ideas called into question and often suppressed; of voices silenced, temporarily or forever; of blind bureaucratic inertia harnessed to moral certainty and to earthly and spiritual power. It is a record of actions taken in the name of religion, though the implications go beyond religion.