God's War: A New History of the Crusades (148 page)

Read God's War: A New History of the Crusades Online

Authors: Christopher Tyerman

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Eurasian History, #Military History, #European History, #Medieval Literature, #21st Century, #Religion, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Religious History

THE WIDER WORLD

Medieval prophets and some post-medieval historians have not been shy to attribute sweeping consequences for the crusade, from a role in the Apocalypse to the opening of the west to new scholarly learning and fresh commercial markets. Such claims have prompted one modern historian to react by reducing crusading’s contribution to western culture to the introduction of the apricot.

85

Yet it is undeniable that both practically and intellectually the traditional western European ambition of occupying Palestine encouraged sensitivity to Christendom’s place in the wider world of the three classical continents of Europe, Asia and Africa. In turn this contributed to an inquisitive and acquisitive expansionism that characterized high and late medieval western European approaches to other peoples and regions near and distant. The extension of western European Christian culture and power to all other parts of the globe provided one of the major features of world history after 1500. In the origins of this process, which formed such as marked contrast to, say, the Chinese experience after 1400, the idealism and activity of crusaders in the four centuries after 1095 played a part.

The intellectual and physical, geographic aspects of the crusade’s

influence on European expansion cannot neatly be separated. Neither should it be exaggerated. The creation of Asiatic empires and the altering of trade routes; the development of the European economy, technology and commerce; or the transmission of classical and Arabic texts via Spain, Sicily, southern Italy and Byzantium ran distinct and parallel to the effect of the wars of the cross. However, crusading idealism led to significant political settlements of Latin Christians in the Near East and, in places, an obsessive European concern for western Asia and the eastern Mediterranean that would not have developed in the way it did without the distinctive dynamism of the crusade mentality and tradition. Politically, the nature of the Muslim powers of the Near East mattered to Frankish rulers and warriors. The acute interest in events further east during the Fifth Crusade stood as an extreme example of a more general concern, evinced, for example, in William of Tyre’s lost history of the Muslim east. Although the irruption of the Mongols into western Asia and eastern Europe owed nothing to crusading, the European response did, in so far as successive missions were despatched to Mongol rulers in the thirteenth century at least in part to test prospects for an anti-Muslim alliance.

The Latin presence in the eastern Mediterranean and the need of prospective western crusaders for information stimulated a small industry of written information about Asia and north Africa from the thirteenth century. This sense of place and desire to acquire knowledge of it was encouraged and sustained by the increasing volume of Holy Land and Near East pilgrimage accounts after 1300, supplemented by memoirs of released captives or western spies, many of which were widely circulated and, in the fifteenth century, printed. While much of the writing about Asia and Africa was fanciful, non-empirical, inaccurate, hidebound by classical texts or vitiated by wishful thinking, it provided a way of looking at the non-Christian, non-European world that transcended mere tales of wonder (although these remained very popular throughout the later middle ages). Asiatic, Muslim and Mongol geography, politics, economy, sociology and demography came under increasingly familiar scrutiny, especially in the large numbers of ‘recovery’ treatises composed between the 1270s and 1330s.

86

These works, by such disparate figures as the Armenian Prince Hayton, who wrote about the Tartars (1307) or the French provincial lawyer Pierre Dubois, who worried about the demographic inequalities of Latins and Saracens

(1306–8), reflected both pragmatic and academic concerns about the nature of the outside world that went far beyond crusade planning.

87

The missions to the Mongols and the opening-up of China to western visitors after the Mongol conquest of 1276 added new geographic horizons, new intellectual challenges and, for some, a new crusading urgency. The introspective idealism of the need to recover Christ’s heritage for Christendom was matched or replaced by a new understanding of the world context of the Holy Land, Christendom and Christianity itself. Such perceptions led directly to the development from the thirteenth century of the idea of crusading for the extension (

dilatio

) of the faith, not just its defence, a concept eagerly embraced and promoted by Iberian crusaders expanding their conquests along the shore of the Maghrib and into the north Atlantic in the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries. The effect of this aggressive concept of holy war, which even tolerated

de facto

wars of conversion previously outlawed, was powerfully displayed from the 1490s in the conquests in the Americas.

88

Jerusalem and the Americas may appear opposite ends of the conceptual as well as geographic map. In fact the road to one led straight to the other. Christopher Columbus was an enthusiast for the recovery of Jerusalem. In later life, he construed his voyages to what he stubbornly viewed as part of the old world as fulfilling biblical prophecies of the reconquest of Jerusalem, notably Isaiah 60:9. In 1501, he wrote to his patrons, the Catholic monarchs of Spain, Ferdinand and Isabella, ‘Our Lord wished to manifest a most evident miracle in this voyage to the Indies in order to console me and others in the matter of the Holy Sepulchre.’

89

Columbus, here and in his own work of prophecy, the

Libro de las profecias

(

Book of Prophecies

), a decade after his first voyage, was casting himself in an almost messianic role as the deliverer of Jerusalem. Such delusional hubris may have startled his royal sponsors, but it sprang from a lively current Spanish interest in outréprophecy, nationalism, the Holy Land and the crusade that the court and policies of Ferdinand and Isabella had done much to excite and foster. Columbus’s interest was grounded on more than apocalyptic dreaming. His will of 1498 provided for a fund to be established in his home city of Genoa for the recovery of Jerusalem.

90

Crusading, far from an anachronism, provided one impetus for the European age of discovery. One of the texts that Columbus may have consulted, and was certainly well known to members of his circle and

people he met, was the pseudonymous John Mandeville’s

Travels

. Its Prologue was unambiguous about the status of the Holy Land, Christ’s heritage, as the centre of the world and about the Christian obligation to recover it by force. ‘Mandeville’s’ account of his supposed travels to Jerusalem, the Near East, Asia and the fabulous Orient provided a rich mine of romance, history, theology, topography and geography. From the original as well as the many contrasting variants, different audiences could extract whatever they desired to inform their own interests, tolerant, bigoted, fanciful or topographical. For Columbus’s circle, the focus on the crusade, which set the frame for ‘Mandeville’, would be of equal attraction as one of the book’s most unequivocal claims: ‘I say with certainty that one could travel around all the lands of the world, both below and above, and return to one’s country’.

91

This assumption of the possibility of circumnavigation was supported by measurements. ‘Mandeville’ rejected the standard medieval calculation of the circumference of the earth, derived from Ptolemy of Alexandria, 20,245 miles, in favour of the more accurate 31,500 miles, Eratosthenes’s figure included in the university textbook

De Spaera

(1230×45) by John of Sacrobosco.

92

For Columbus, even if not directly influenced by ‘Mandeville’, which he may have been, science, cosmology and the crusade were complementary, not aspects of antagonistic cultures or hostile systems of thought. In contemplating ways of fulfilling the injunction to recover Christ’s heritage, Columbus, like so many of his would-be crusader predecessors stretching back to Urban II’s call to arms at Clermont, first sought to understand the world better, its natural phenomena, its diversity and its breadth as much as its eschatalogical destiny. Crusading remained embedded in western European culture for so long precisely for this reason. In presenting a spiritualized vision of reality, it recognized the temporal world and the actual experience of man while offering to transform both.

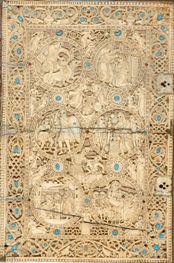

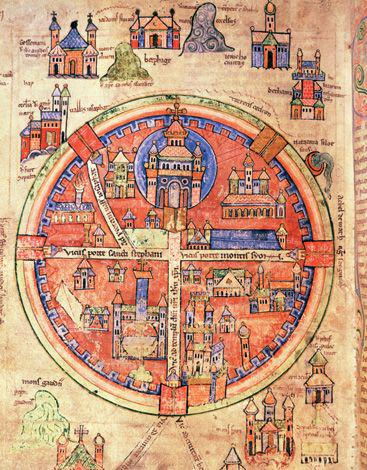

1. Jerusalem and its environs

c

.1100: the Holy City in the eyes of western Christendom.

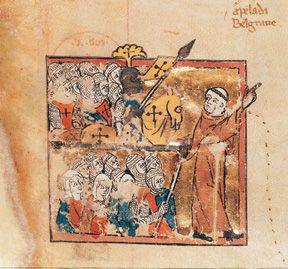

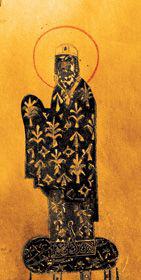

2. Urban II consecrating the high altar at Cluny during his preaching tour of France, October 1095; see p.

63

.

3. Peter the Hermit leading his crusaders.

4. Alexius I Comnenus, emperor of Byzantium 1081–1118.

5. The church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem idealized in later medieval western imagination.