God's War: A New History of the Crusades (150 page)

Read God's War: A New History of the Crusades Online

Authors: Christopher Tyerman

Tags: #Non-Fiction, #Eurasian History, #Military History, #European History, #Medieval Literature, #21st Century, #Religion, #v.5, #Amazon.com, #Retail, #Religious History

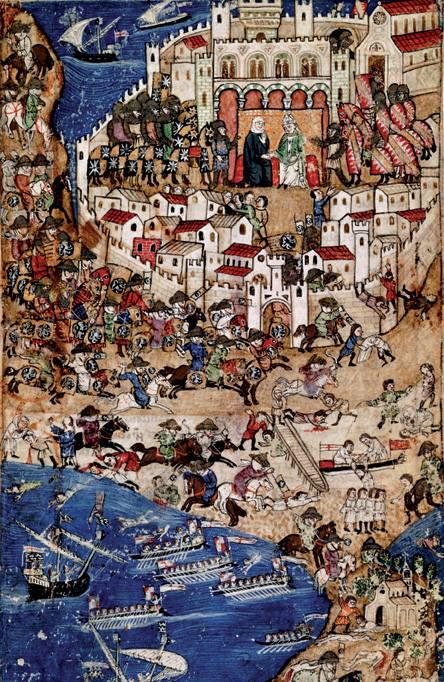

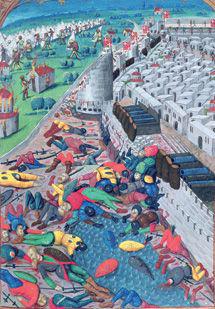

19. The Fifth Crusade: the capture of the Tower of Chains by Oliver of Paderborn’s floating fortress, August 1218 (

left

), and the fall of Damietta, November 1219 (

right

), from Matthew Paris’s

Chronica Majora, c

.1255.

20. Frederick II, emperor, king of Germany 1212–50, ruler, crusader, polymath and falconry expert.

21. Louis IX of France captures Damietta, June 1249, from a manuscript produced at Acre

c

.1280. Not a cross in sight; instead the crusaders bear the royal emblem of France, the fleur de lis; see p.

909

.

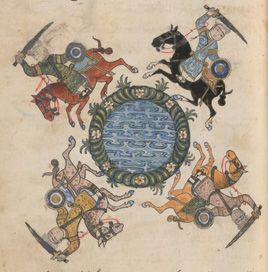

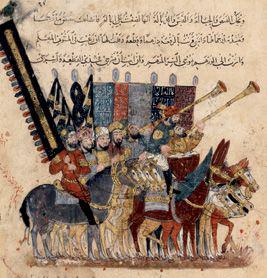

22. Outremer’s nemesis: Mamluk warriors training.

23. Outremer’s nemesis: a Turkish cavalry squadron.

24. The battle of La Forbie, October 1244: a Khwarazmian and Egyptian army annihilate a Frankish-Damascene force; see p.

771

.

25. Matthew Paris imagines the Mongols as cannibalistic savages,

Chronica Majora, c

.1255.

26. The fall of Tripoli to the Mamluks, April 1289; see p.

817

.

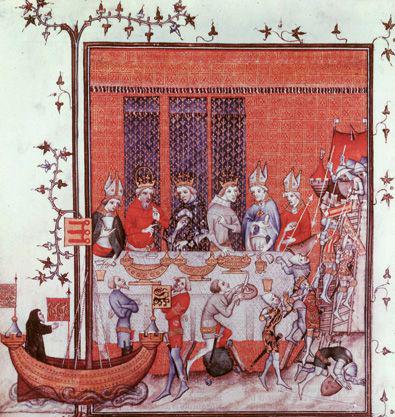

27. Charles V of France entertains Charles IV of Germany during a banquet in Paris in 1378 with a lavish show of the siege of Jerusalem of 1099, possibly stage-managed by Philip of Mézières, perhaps the figure in black shown in the left foreground; see p.

887

.

28. Andrea Bonaiuti’s fresco ‘The Church Militant’ in the Spanish Chapel, St Maria Novella, Florence, portraying the leading lights in crusading at the time (

back row, right to left, beginning with the black-bearded noble carrying a sword

): Amadeus VI count of Savoy, King Peter I of Cyprus, the Emperor Charles IV, Pope Urban V, the papal legate in Italy, Gil Albornoz; (

back row, fourth from far left

) Juan Fernandez Heredia, master of the Hospitallers; and, standing in front of Peter of Cyprus, Thomas Beauchamp earl of Warwick, wearing the insignia of the Order of the Garter below his left knee. See p.

832

.

29. The failed Ottoman Turkish siege of Rhodes, 1480.

30. Mehmed II the Conqueror (1451–81) by Gentile Bellini, 1480/81.

31. The battle of Lepanto, 1571; see pp.

903–4

.

Conclusion

Popes today do not summon crusades. There are a number of reasons for this. One part of Christendom decisively rejected the theology behind the medieval wars of the cross in the sixteenth century. The Roman Catholic church itself refined its own teaching to modify its penitential practices in ways that undermined the fiscal and liturgical accoutrements of later medieval crusading. Crusade ideology had hardly developed since Innocent III. Based essentially on patristic and scholastic theology – and loosely at that – its justification looked increasingly awkward in the face of sixteenth-century scriptural theology and attacks founded on the New Testament. The increasing interiorization of faith, shared to some degree by all sides of the major confessional divides, militated against certain of the showier forms of medieval devotion that crusading exemplified, the increasingly controversial sale of indulgences merely being the most notorious. Men could and did still take the cross, perhaps even into the eighteenth century against Turks and Barbary pirates. The war of the Holy League against the Ottomans, 1684–99, was probably the last formal crusade. But these gestures were divorced from the communal round of devotional practices or cultural aesthetics. Although in times of crisis, such as the First World War, over-excited prelates can still urge their congregations to fight the good temporal as well as spiritual fight, and while the secular legalism of just war continues to attract advocates, most non-literalist Christian denominations now shun the tradition of holy war, some even pretending it was a kind of aberration. In the later twentieth century, the Roman Catholic church was careful not to embrace potentially violent (and certainly radical) theologies, such as Liberation Theology. John Paul II even apologized to victims of the crusades. The wars of the cross have become like a lingering bad smell in a lavishly refurbished stately home.