Gravity's Rainbow (110 page)

Authors: Thomas Pynchon

Past Slothrops, say averaging one a day, ten thousand of them, some more powerful

than others, had been going over every sundown to the furious host. They were the

fifth-columnists, well inside his head, waiting the moment to deliver him to the four

other divisions outside, closing in. . . .

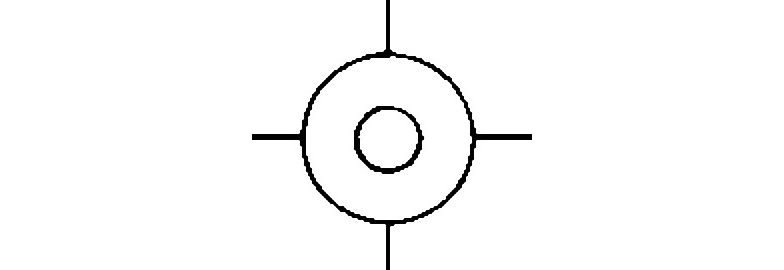

So, next to the other graffiti, with a piece of rock, he scratches this sign:

Slothrop besieged. Only after he’d left it half a dozen more places did it dawn on

him that

what he was really drawing was the A4 rocket

, seen from below. By which time he had become tuned to other fourfold expressions—variations

on Frans Van der Groov’s cosmic windmill—swastikas, gymnastic symbols FFFF in a circle

symmetrically upside down and backward, Frisch Fromm Frölich Frei over neat doorways

in quiet streets, and crossroads, where you can sit and listen in to traffic from

the Other Side, hearing about the future (no serial time over there: events are all

there in the same eternal moment and so certain messages don’t always “make sense”

back here: they lack historical structure, they sound fanciful, or insane).

The sand-colored churchtops rear up on Slothrop’s horizons, apses out to four sides

like rocket fins guiding the streamlined spires . . . chiseled in the sandstone he

finds waiting the mark of consecration, a cross in a circle. At last, lying one afternoon

spread-eagled at his ease in the sun, at the edge of one of the ancient Plague towns

he becomes a cross himself, a crossroads, a living intersection where the judges have

come to set up a gibbet for a common criminal who is to be hanged at noon. Black hounds

and fanged little hunters slick as weasels, dogs whose breeds have been lost for 700

years, chase a female in heat as the spectators gather, it’s the fourth hanging this

spring and not much spectacle here except that this one, dreaming at the last instant

of who can say what lifted smock, what fat-haunched gnädige Frau Death may have come

sashaying in as, gets an erection, a tremendous darkpurple swelling, and just as his

neck breaks, he actually

comes

in his ragged loin-wrapping creamy as the skin of a saint under the purple cloak

of Lent, and one drop of sperm succeeds in rolling, dripping hair to hair down the

dead leg, all the way down, off the edge of the crusted bare foot, drips to earth

at the exact center of the crossroad where, in the workings of the night, it changes

into a mandrake root. Next Friday, at dawn, the Magician, his own moving Heiligenschein

rippling infrared to ultraviolet in spectral rings around his shadow over the dewy

grass, comes with his dog, a coal-black dog who hasn’t been fed for a few days. The

Magician digs carefully all around the precious root till it’s held only by the finest

root-hairs—ties it to the tail of his black dog, stops his own ears with wax then

comes out with a piece of bread to lure the unfed dog

rrrowf!

dog lunges for bread, root is torn up and lets loose its piercing and fatal scream.

The dog drops dead before he’s halfway to breakfast, his holy-light freezes and fades

in the million dewdrops. Magician takes the root tenderly home, dresses it in a little

white outfit and leaves money with it overnight: in the morning the cash has multiplied

tenfold. A delegate from the Committee on Idiopathic Archetypes comes to visit. “Inflation?”

the Magician tries to cover up with some flowing hand-moves.” ‘Capital’? Never heard

of that.” “No, no,” replies the visitor, “not at the moment. We’re trying to think

ahead. We’d like very much to hear about the basic structure of this. How bad was

the scream, for instance?” “Had m’ears plugged up, couldn’t hear it.” The delegate

flashes a fraternal business smile. “Can’t say as I blame you. . . .”

Crosses, swastikas, Zone-mandalas, how can they not speak to Slothrop? He’s sat in

Säure Bummer’s kitchen, the air streaming with kif moirés, reading soup recipes and

finding in every bone and cabbage leaf paraphrases of himself . . . news flashes,

names of wheelhorses that will pay him off enough for a certain getaway. . . . He

used to pick and shovel at the spring roads of Berkshire, April afternoons he’s lost,

“Chapter 81 work,” they called it, following the scraper that clears the winter’s

crystal attack-from-within, its white necropolizing . . . picking up rusted beer cans,

rubbers yellow with preterite seed, Kleenex wadded to brain shapes hiding preterite

snot, preterite tears, newspapers, broken glass, pieces of automobile, days when in

superstition and fright he could

make it all fit

, seeing clearly in each an entry in a record, a history: his own, his winter’s, his

country’s . . . instructing him, dunce and drifter, in ways deeper than he can explain,

have been faces of children out the train windows, two bars of dance music somewhere,

in some other street at night, needles and branches of a pine tree shaken clear and

luminous against night clouds, one circuit diagram out of hundreds in a smudged yellowing

sheaf, laughter out of a cornfield in the early morning as he was walking to school,

the idling of a motorcycle at one dusk-heavy hour of the summer . . . and now, in

the Zone, later in the day he became a crossroad, after a heavy rain he doesn’t recall,

Slothrop sees a very thick rainbow here, a stout rainbow cock driven down out of pubic

clouds into Earth, green wet valleyed Earth, and his chest fills and he stands crying,

not a thing in his head, just feeling natural. . . .

• • • • • • •

Double-declutchingly, heel-and-toe, away goes Roger Mexico. Down the summer Autobahn,

expansion joints booming rhythmic under his wheels, he highballs a pre-Hitler Horch

870B through the burnt-purple rolling of the Lüneburg Heath. Over the windscreen mild

winds blow down on him, smelling of junipers. Heidschnucken sheep out there rest as

still as fallen clouds. The bogs and broom go speeding by. Overhead the sky is busy,

streaming, a living plasma.

The Horch, army-green with one discreet daffodil painted halfway up its bonnet, was

lurking inside a lorry at the Elbeward edge of the Brigade pool at Hamburg, shadowed

except for its headlamps, stalked eyes of a friendly alien smiling at Roger. Welcome

there, Earthman. Once under way, he discovered the floor strewn with rolling unlabeled

glass jars of what seems to be baby food, weird unhealthy-colored stuff no human baby

could possibly eat and survive, green marbled with pink, vomit-beige with magenta

inclusions, all impossible to identify, each cap adorned with a smiling, fat, cherubic

baby, seething under the bright glass with horrible botulism toxins ’n’ ptomaines . . .

now and then a new jar will be produced, spontaneously, under the seat, and roll out,

against all laws of acceleration, among the pedals for his feet to get confused by.

He knows he ought to look back underneath there to find out what’s going on, but can’t

quite bring himself to.

Bottles roll clanking on the floor, under the bonnet a hung-up tappet or two chatters

its story of discomfort. Wild mustard whips past down the center of the Autobahn,

perfectly two-tone, just yellow and green, a fateful river seen only by the two kinds

of rippling light. Roger sings to a girl in Cuxhaven who still carries Jessica’s name:

I dream that I have found us both again,

With spring so many strangers’ lives away,

And we, so free,

Out walking by the sea,

With someone else’s paper words to say. . . .

They took us at the gates of green return,

Too lost by then to stop, and ask them why—

Do children meet again?

Does any trace remain,

Along the superhighways of July?

Driving now suddenly into such a bright gold bearding of slope and field that he nearly

forgets to steer around the banked curve. . . .

A week before she left, she came out to “The White Visitation” for the last time.

Except for the negligible rump of PISCES, the place was a loony bin again. The barrage-balloon

cables lay rusting across the sodden meadows, going to flakes, to ions and earth—tendons

that sang in the violent nights, among the sirens wailing in thirds smooth as distant

wind, among the drumbeats of bombs, now lying slack, old, in hard twists of metal

ash. Forget-me-nots boil everywhere underfoot, and ants crowd, bustling with a sense

of kingdom. Commas, brimstones, painted ladies coast on the thermoclines along the

cliffs. Jessica has cut fringes since Roger saw her last, and is going through the

usual anxiety—“It looks utterly horrible, you don’t have to say it. . . .”

“It’s utterly swoony,” sez Roger, “I love it.”

“You’re making fun.”

“Jess, why are we talking about

haircuts

for God’s sake?”

While somewhere, out beyond the Channel, a barrier difficult as the wall of Death

to a novice medium, Leftenant Slothrop, corrupted, given up on, creeps over the face

of the Zone. Roger doesn’t want to give him up: Roger wants to do what’s right. “I

just can’t leave the poor twit out there, can I? They’re trying to destroy him—”

But, “Roger,” she’d smile, “it’s

spring.

We’re at peace.”

No, we’re not. It’s another bit of propaganda. Something the P.W.E. planted. Now gentlemen

as you’ve seen from the studies our optimum time is 8 May, just before the traditional

Whitsun exodus, schools letting out, weather projections for an excellent growing

season, coal requirements beginning their seasonal decline, giving us a few months’

grace to get our Ruhr interests back on their feet—no, he sees only the same flows

of power, the same impoverishments he’s been thrashing around in since ’39. His girl

is about to be taken away to Germany, when she ought to be demobbed like everyone

else. No channel upward that will show either of them any hope of escape. There’s

something

still on, don’t call it a “war” if it makes you nervous, maybe the death rate’s gone

down a point or two, beer in cans is back at last and there

were

a lot of people in Trafalgar Square one night not so long ago . . . but Their enterprise

goes on.

The sad fact, lacerating his heart, laying open his emptiness, is that Jessica believes

Them. “The War” was the condition she needed for being with Roger. “Peace” allows

her to leave him. His resources, next to Theirs, are too meager. He has no words,

no technically splendid embrace, no screaming fit that can ever hold her. Old Beaver,

not surprisingly, will be doing air-defense liaison over there, so they’ll be together

in romantic Cuxhaven. Ta-ta mad Roger, it’s been grand, a wartime fling, when we came

it was utterly incendiary, your arms open wide as a Fortress’s wings, we had our military

secrets, we fooled the fat old colonels right and left but stand-down time must come

to all, yikes! I must run sweet Roger really it’s been dreamy. . . .

He would fall at her knees smelling of glycerine and rose-water, he would lick sand

and salt from her ATS brogans, offer her his freedom, his next 50 years’ pay from

a good steady job, his poor throbbing brain. But it’s too late. We’re at Peace. The

paranoia, the danger, the tuneless whistling of busy Death next door, are all put

to sleep, back in the War, back with her Roger Mexico Years. The day the rockets stopped

falling, it began to end for Roger and Jessica. As it grew clear, day after safe day,

that no more would fall ever again, the new world crept into and over her like spring—not

so much the changes she felt in air and light, in the crowds at Woolworth’s, as a

bad cinema spring, full of paper leaves and cotton-wool blossoms and phony lighting . . .

no, never again will she stand at their kitchen sink with a china cup squeaking in

her fingers, its small crying-child sound defenseless, meekly resonating BLOWN OUT

OF ATTENTION AS THE ROCKET FELL smashing to a clatter of points white and blue across

the floor. . . .

Those death-rockets now are in the past. This time she’ll be on the firing end, she

and Jeremy—isn’t

that

how it was always meant to be? firing them out to sea: no death, only the spectacle,

fire and roar, the excitement without the killing, isn’t that what she prayed for?

back in the fading house, derequisitioned now, occupied again by human extensions

of ball-fringe, dog pictures, Victorian chairs, secret piles of

News of the World

in the upstairs closet.

She’s meant to go. The orders come from higher than she can reach. Her future is with

the World’s own, and Roger’s only with this strange version of the War he still carries

with him. He can’t move, poor dear, it won’t let him go. Still passive as he’d been

under the rockets. Roger the victim. Jeremy the firer. “The War’s my mother,” he said

the first day, and Jessica has wondered what ladies in black appeared in his dreams,

what ash-white smiles, what shears to come snapping through the room, through their

winter . . . so much of him she never got to know . . . so much unfit for Peace. Already

she’s beginning to think of their time as a chain of explosions, craziness ganged

to the rhythms of the War. Now he wants to go rescue Slothrop, another rocket-creature,

a vampire whose sex life actually

fed

on the terror of that Rocket Blitz—ugh, creepy, creepy. They ought to lock him up,

not set him free. Roger

must

care more about Slothrop than about her, they’re two of a kind, aren’t they, well—she

hopes they’ll be happy together. They can sit and drink beer, tell rocket stories,

scribble equations for each other. How jolly. At least she won’t be leaving him in

a vacuum. He won’t be lonely, he’ll have something to occupy the time. . . .