Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (19 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

Rocket production began on December 10, 1943. Both Himmler and Speer were highly impressed, and Speer wrote to Kammler on December 17 with ringing praise for his accomplishment, one “that

far exceeds anything ever done in Europe

and is unsurpassed even by American standards.” Production was originally projected at a rate of 900 rockets a month, at a cost of 100,000 reichsmarks each—ten times the cost of a V-1 flying bomb. However, peak production only reached 690 units, in January 1945; a total of 6,422 V-2s were built.

Hitler authorized Operation Penguin on August 29, 1944. By late March 1945, the German had launched 3,172 V-2s, of which 1,402 were fired at cities in England, 1,664 at targets in Belgium, 76 at France, 19 at Holland, and 11 against the Ludendorff Bridge after it was captured by American troops. It is estimated that Operation Penguin killed some 7,250 people over a period of seven months. Again, though the toll in human misery was immense, this average of 2.28 deaths per rocket launched at Allied targets was a remarkably low return for the investment. Of course, to that total must be added the deaths of some 20,000 slave workers at Mittelwerk and about 2,000 Allied airmen who were killed during Operations Crossbow and Big Ben in the hunt for V-weapons facilities and launching sites. At the peak of Operation Penguin in March 1945, about

sixty missiles per week

were striking England, carrying a grand total of 250 tons of explosives that randomly destroyed suburban streets. In the same month, the Allied air forces dropped 133,329 tons of bombs on Germany, laying waste whole cities.

The true money cost of the

Vergeltungswaffen

program is impossible to ascertain, but a postwar U.S. intelligence assessment put the price at almost $2 billion—about the same amount as the Manhattan Project. For the same cost as 6,422 V-2 missiles, German industry could have produced 6,000 Panther tanks or 12,000 Focke-Wulf Fw 190 fighter aircraft that would have been immeasurably more useful in the defense of the Reich. Nevertheless, the Americans were quick to appreciate the significance of the ballistic missile. It was technology they wanted for themselves at any price.

FOLLOWING THE LIBERATION OF PARIS

in August 1944, the Allied armies fanned out across France in headlong pursuit of the retreating German forces. The British Second Army liberated Brussels on September 3 and the port of Antwerp the day after, just as the U.S. First Army reached Luxembourg and Patton’s Third Army arrived at the Moselle River.

Confidence was so high

that Gen. Marshall even advised President Roosevelt that the war in Europe would be over “sometime between September 1 and November 1, 1944.” The various specialized Allied search units tried to keep up with the advancing armor and infantry. The Germans’ retreat was so rapid that their army was rarely able to implement the scorched-earth policy demanded by Hitler. Nevertheless, many bridges and buildings were mined and booby-trapped, among them

Chartres Cathedral

, the twelfth-century Gothic masterpiece in Chartres, France. Capt. Walker Hancock, the “Monuments Man” for the U.S. First Army, was quickly on the scene with MFA&A demolitions specialist Capt. Stewart Leonard. With infinite patience, Leonard defused the twenty-two separate demolition charges. When asked by another Monuments Man whether it was right to risk his life for art, Leonard responded, “I had that choice. I chose to remove the bombs. It was worth the reward.” “What reward?” “When I finished, I got to sit in Chartres Cathedral—the cathedral I helped save—for almost an hour. Alone.”

But the Monuments Men were not always able to reach their objectives in time. On the night of September 7, just hours before the arrival of the Allies, the Bruges Madonna sculpture by Michelangelo was stolen from the Cathedral of Notre Dame in Bruges and shipped off to Germany. The task of the MFA&A teams was immense; the U.S. First, Third, Ninth, and Fifteenth Armies, with some 1.3 million troops, had just nine frontline MFA&A personnel, and in all there were only 350 people working for the organization in the whole European theater of operations.

Moreover, in the fall of 1944, the Allied advance faltered due to a lack of supplies—particularly gasoline—reaching the frontline troops. The railroad system of northern Europe had been completely destroyed by Allied bombing, and the failure to capture a major port intact was proving critical; the approaches to Antwerp from the sea were still in German hands and the city was now under constant bombardment by V-1 and V-2 missiles. Lacking the resources to advance on a broad front, but heartened by the

apparent imminence of German defeat

, SHAEF embarked on Operation Market Garden, a bold strategy of using the three divisions of the First Allied Airborne Army to seize vital bridges along a narrow corridor through Holland and on to the River Rhine, the last natural obstacle protecting the Ruhr and the heartlands of Germany. Despite worrisome Ultra decrypts, aerial reconnaissance photos, and warnings from the Dutch Resistance suggesting that major SS tank units stood in the path of this attempt, the high command went ahead with Operation Market Garden on September 17, 1944. Despite the skill and bravery of the American, British, and Polish paratroopers, the operation failed, ending in the destruction of the British 1st Airborne Division at

Arnhem

.

By October 1944, the mood of the Allied high command had switched from euphoria to despondency, just as the weather turned foul. In the north, the British and Canadians fought a wretched, muddy campaign to clear the banks of the Scheldt Estuary in order to open Antwerp to Allied shipping. The U.S. First Army was to be held up by the battle for the Hürtgen Forest from September 1944 to February 1945. Further south, the U.S. Third Army ground to a halt in Alsace-Lorraine, just short of Metz on the Moselle River, purely due to a lack of fuel; this delay allowed the Germans to reinforce that heavily fortified city for

another grueling battle

. In the breakout from Normandy, Patton’s Third Army had advanced 500 miles in less than a month, and suffered just 1,200 casualties; over the next three months it would advance one-tenth that distance and suffer forty times the casualties. The war would by no means be over by Christmas.

GEN. LESLIE GROVES, THE DIRECTOR

of the Manhattan Project, remained highly concerned as to the whereabouts of 1,200 tons of uranium ore belonging to the Union Minière—a Belgian uranium mining company based in the Congo—that the Germans had captured in 1940. Once processed into the isotope uranium-235, such an amount was sufficient to make several viable atomic bombs, which required about 140 pounds of enriched uranium each. After their foray into Paris in late August 1944, Col. Boris Pash and the Alsos team traveled to Toulouse in southern France to follow up on a tip-off. There they found 31 tons of the uranium ore stored in a French naval arsenal. The haul was immediately shipped to the Manhattan Project’s production facility in Oak Ridge, Tennessee, to be processed through the

electromagnetic separation calutrons

into enriched uranium for “Little Boy,” the uranium bomb being developed at the project’s massive laboratory in Los Alamos, Nevada.

Back in southern France, Col. Pash had procured several half-tracks, armored cars, and armed jeeps; thus mounted and armed, the Alsos unit followed the advance of the Allied forces toward the German border. In November 1944, the team arrived in newly liberated Strasbourg, in whose university they found a nuclear physics laboratory and bundles of documents. These revealed that the German nuclear weapons development program—known as Uranverein, the “Uranium Club”—was not only in its infancy, but based on flawed science. This confirmed the earlier British intelligence assessment, but

Gen. Groves was still not satisfied

. Fortuitously, other documents revealed the locations of all laboratories working with Uranverein

,

greatly simplifying Col. Pash’s mission once the Allies advanced into Germany.

Groves was equally determined to forestall the chance of any Uranium Club scientists or their documents falling into the hands of the Soviet Union—whose own nuclear program, as we now know, was only a matter of months behind the U.S. research, thanks to the comprehensive penetration of the Manhattan Project by Soviet spies. Germany’s leading theoretical physicist was Werner Heisenberg, who occasionally traveled to occupied Denmark or neutral Switzerland to give scientific papers and lectures. Groves proposed that Heisenberg be kidnapped during one of these trips and interrogated to ascertain the extent of German progress. If that was not possible, then Heisenberg should be assassinated—in Groves’s telling words, “

Deny the enemy his brain

.” The task was given to an OSS agent named Morris “Moe” Berg, a former catcher and coach with the Boston Red Sox. Berg was also a graduate of Princeton who had studied seven languages, including Sanskrit. Now he immersed himself in the theory and practice of nuclear physics so that he would be able to follow Heisenberg’s next university lecture, to be held on December 18, 1944, at the Physics Institute of the Eidgenössische Technische Hochschule (ETH) in Zurich, Switzerland.

During the last week of November, Moe Berg arrived in Bern to be briefed by the OSS station chief, Allen Dulles. Like Groves, Dulles was now firmly convinced that the Soviet Union posed a greater threat to Western interests than the death throes of the Third Reich, so, given the danger that the former might inherit the latter’s resources in this field, he was happy to assist. It seems that by this time the kidnapping mission had turned into an assassination mission. Berg noted at the time, “

Nothing spelled out

, but Heisenberg must be rendered hors de combat. Gun in my pocket.” This was a .22-caliber Hi-Standard automatic with a sound suppressor; he was also given a cyanide pill in case escape became impossible after the assassination. Admission to Heisenberg’s lecture was not a problem, since one of Dulles’s innumerable contacts was Dr. Paul Scherrer, the director of the Physics Institute at ETH. Scherrer had organized many such lectures and always passed on any pertinent information to the OSS and MI6.

Heisenberg’s presentation concerned quantum mechanics rather than nuclear physics; it did nothing to help Berg decide his course of action so he arranged to have dinner with Heisenberg at Scherrer’s home. During the course of the conversation, Heisenberg reveled in the success of the ongoing German offensive in the Ardennes, but when asked if Germany was going to lose the war, he replied, “Yes—but it would have been so good if we had won.” This comment probably saved his life, as it showed that Germany did not possess any weapons of mass destruction that might contribute to another outcome. The

pistol remained in Moe Berg’s pocket

.

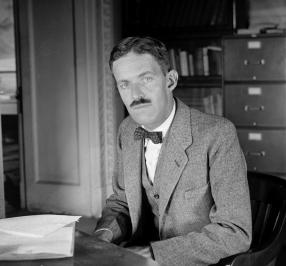

A YOUNG ALLEN WELSH DULLES in his office at the State Department, 1924. Allen Dulles joined the OSS in 1942 before moving to Bern in Switzerland in October, where he became one of the most successful spymasters of World War II, with numerous contacts across occupied Europe and with the Nazi high command.

ALLEN WELSH DULLES [left] greets his brother John Foster Dulles after a flight on October 4, 1948. After the war, Allen Dulles became the director of the Central Intelligence Agency while John Foster Dulles became secretary of state during the Eisenhower administration. Together, they were among the most influential American officials of the immediate postwar period and leading figures in the Cold War confrontation with the Soviet Union.