Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (14 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

Bormann’s money-laundering process was repeated with companies in Portugal, Spain, Sweden, and Turkey as well. By 1945, he had amassed some $18 million in Swedish kroner and $12 million in Turkish lira, with major deposits in the Stockholms Enskilda Bank and in the Deutsche Bank and the Deutsche Orientbank, both in Istanbul.

Another major aspect of Project Eagle Flight was the acquisition of shares or equity in foreign companies, especially in North America. For this, Bormann turned to the past master of the game, IG Farben. Since the time of its formation in 1926, IG Farben had acquired numerous American companies as part of its worldwide cartel. By the time Germany declared war on the United States shortly after Pearl Harbor, IG Farben held a voting majority in 170 American companies and minority holdings in another 108. Bormann turned for advice to its president, Hermann Schmitz, and to the former Reich economics minister, Dr. Hjalmar Schacht. Together they were able to coordinate the transfer of Nazi funds through Swiss banks, via the Bank for International Settlements, or through third parties and companies. As a case in point, through their Stockholms Enskilda Bank (SEB), the Swedish brothers Jacob and Marcus Wallenberg purchased the American Bosch Corporation, the U.S. subsidiary of Robert Bosch GmbH of Stuttgart, on behalf of the Bormann “Organization” but with the Wallenbergs as nominal owners. For their pains, they were paid with 2,350 pounds of gold bullion deposited in a Swiss numbered account on behalf of SEB. This Stockholm bank also bought stocks and bonds for Bormann on the New York Stock Exchange and made substantial loans to the Norsk Hydro ASA plant in Rjukan, Norway, which was crucial in the manufacture of “

heavy water

” for the Nazi atomic weapons program. Needless to say, IG Farben was the majority shareholder in Norsk Hydro ASA.

By these means, Bormann was able to

create some 980 front companies

, with 770 of these in neutral countries, including 98 in Argentina, 58 in Portugal, 112 in Spain, 233 in Sweden, 234 in Switzerland, and 35 in Turkey—no doubt there were others whose existence has never been revealed. Every single one was a conduit for the flight of capital from Germany, just waiting for Bormann to give the order when the time was right. In the best IG Farben tradition, ultimate title to the companies was a closely guarded secret maintained through a number of subterfuges, as described succinctly by the celebrated CBS Radio journalist Paul Manning, author of

Martin Bormann: Nazi in Exile

: “Bormann utilized

every known device

to disguise their ownership and their patterns of operations: use of nominees, option agreements, pool agreements, endorsements in blank, escrow deposits, pledges, collateral loans, rights of first refusal, management contracts, service contracts, patent agreements, cartels, and withholding procedures.” The most important of these instruments were bearer bonds. These are securities issued by banks, companies, or even by governments, often in times of crisis, in any given value. They are unregistered; no records are kept of the owners or of any transactions involved, so they are highly attractive to investors who wish to remain anonymous. Whoever physically held the paper on which the bond was issued owned the investment security, so a bearer bond issued in Zurich could be cashed in Buenos Aires or elsewhere with impunity. As Hitler declared to Bormann: “

Bury your treasure deep

, as you will need it to begin the Fourth Reich.”

INSEPARABLE FROM SECURING THE FINANCIAL ASSETS

of the Third Reich was the need to preserve the Nazi leadership, in particular Adolf Hitler and his immediate entourage. Any refuge for Hitler had to be chosen with care. When the British were faced with a similar situation in the summer of 1940, it had been a relatively simple matter; if the threat of invasion from across the Channel had become a reality and the plans for containing the German beachhead had failed, then the powerful Royal Navy would have transported the royal family and the government to Canada, to continue the war from the dominions and colonies. Germany, on the other hand, no longer had an overseas empire, since the Treaty of Versailles had stripped her of her few colonies in Africa and the Pacific in 1919.

However, there was still a kind of de facto German overseas colony in Latin America, where many thousands of Germans had emigrated in previous generations. These communities were cohesive and commercially active, and Bormann had access to them through the NSDAP Auslands-Organisation. A file was brought to his attention that had been written during World War I by the young naval intelligence officer Wilhelm Canaris, describing his escape in 1915 from internment in Chile via Patagonia—the vast, sparsely inhabited region of southern Chile and Argentina that had a predominantly German settler population.

Lt. Canaris had been sheltered by the German community around a small town in the foothills of the Argentine Andes. Its isolation and the strongly patriotic German influence among the local population were significant factors. However, if this place was to be selected for such an all-important and top-secret project, then the attitude of the Argentine national government would be equally important. Fortunately, a military coup d’état in Buenos Aires in June 1943 brought to power a regime sympathetic to Nazi Germany—indeed, a highly placed member of the new government, Col. Juan Domingo Perón, had already been on the German intelligence payroll for two years. With massive funds already deposited in Argentina, a cooperative regime in power, and a significant part of the nation’s industry and commerce owned by people of German extraction, the pieces were now in place for the execution of a concerted plan.

Bormann’s scheme was code-named Aktion Feuerland (Project Land of Fire) in reference to Patagonia’s southern tip, the archipelago Tierra del Fuego (Spanish for “Land of Fire”). The plan’s object was to create a secret,

self-contained refuge for Hitler

in the heart of a sympathetic German community, at a chosen site near the town of San Carlos de Bariloche in the far west of Argentina’s Río Negro province. Here the Führer could be provided with complete protection from outsiders since all routes in by road, rail, or air were in the hands of Germans. In mid-1943, Bormann’s chief agent in Buenos Aires, a banking millionaire named Ludwig Freude, put the work in hand.

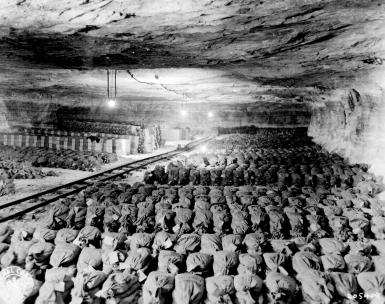

In April 1945, the U.S. 90th Infantry Division discovered a trove of Nazi loot and art in a salt mine in Merkers, Germany.

AMONG THE BRITISH FORCES that landed in French North Africa during Operation Torch in November 1942 was a new unit on its first major operation—30 Commando Unit (CU). Primarily, 30 CU was tasked with gathering military intelligence documents and items of enemy weapons technology before they could be hidden or destroyed. The unit had been conceived in the British Admiralty, and the Royal Navy was particularly anxious to gather any intelligence concerning the sophisticated Enigma encryption machines that were used to communicate with Adm. Dönitz’s U-boats at sea. The

Naval Intelligence Commando Unit

was the brainchild of Lt. Cdr. Ian Fleming of the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve (RNVR)—the future creator of the quintessential fictional spy James Bond. Fleming was recruited in 1939 by Vice Adm. John Godfrey, director of naval intelligence, as his personal assistant. On March 24, 1942, Fleming’s proposal for the new unit landed on the admiral’s desk.

Fleming had been influenced by the exploits of the Abwehr-kommando—German clandestine special forces, often disguised in Allied or neutral uniforms. The

Abwehrkommando

had performed most effectively against the Allies during the invasions of Holland, Yugoslavia, Greece, Crete, and the USSR. Formed on October 15, 1939, as part of Adm. Canaris’s Abwehr, the obscurely titled Lehr und Bau Kompanie zbV 800 (Special Duty Training and Construction Company No. 800) was commanded by Capt. Theodor von Hippel and based at the Generalfeldzeugmeister-Kaserne barracks in Brandenburg, Prussia. Thereafter the unit adopted the name of that town as its informal title—the Brandenburgers. On May 20, during the initial German paratroop drop at Maleme airfield during Germany’s airborne invasion of the island of Crete, a special forces unit led the assault on the British headquarters, with the specific task of capturing military intelligence documents and codebooks—fortunately, it found nothing related to Ultra intelligence (see

Chapter 1

). It was reports of this mission that prompted Ian Fleming to write his missive to Godfrey proposing a similar raiding force.

At the outset,

Fleming’s “Red Indians,”

as he liked to call them, were given the cover name of the Special Engineering Unit of the Special Service Brigade, which was under the operational control of the Chief of Combined Operations, Adm. Lord Louis Mountbatten. Accordingly, after completing training, its personnel were entitled to wear the coveted green beret, as well as drawing a daily special-service allowance to enhance their pay. Subsequently, the group’s title was changed to 30 Commando Unit; the “30” related to the room number at the Admiralty in Whitehall, London, occupied by Fleming’s legendary secretary Miss Margaret Priestley, a history don from Leeds University and the inspiration for Miss Moneypenny in his James Bond novels.

The unit comprised three elements: No. 33 Royal Marine Troop, which provided the fighting element during operations; No. 34 Army Troop; and No. 36 Royal Navy Troop. Originally there was to have been a No. 35 RAF Troop, but the Royal Air Force never seconded the necessary personnel. Like all such special forces units, 30 CU attracted some extraordinary characters. Its first commanding officer was Cdr. Robert “Red” Ryder, Royal Navy, who had just been awarded the Victoria Cross, Britain’s supreme decoration for gallantry in battle, for his exceptional valor and leadership in the destruction of the vital lock gates of the Normandie dock at St. Nazaire during Operation Chariot earlier in the year. This brilliant but costly raid denied the Kriegsmarine any docking facilities on the Atlantic coast for its capital ships such as the

Tirpitz

.

Despite coming under Combined Operations, 30 CU reported directly to Fleming in his capacity as personal assistant to the director of naval intelligence. The unit was first deployed during Operation Jubilee, the ill-fated Dieppe raid on August 12, 1942, but their gunboat HMS

Locust

was struck several times by gunfire on entering the harbor and was forced out to sea before any troops could be landed. One of the primary reasons for the failure of Operation Jubilee was the fact that German signals intelligence had broken Royal Navy codes and had full knowledge of the planned raid some five days before it was launched.

FOR OPERATION TORCH

, 30 Commando Unit landed from HMS

Malcolm

on November 8, 1942, at Sidi Ferruch in the Bay of Algiers, together with an assault force of American troops from the U.S. 34th Infantry Division. Advancing with the leading infantry, No. 33 Troop, commanded by Lt. Dunstan Curtis, RNVR, captured several buildings in their quest for intelligence. Because of the peculiar terms of the armistice that was soon concluded with the Vichy French authorities, Curtis and his men needed all their ingenuity to uncover material from places guarded by the French police. In addition, 30 CU captured an Abwehr officer named

Maj. Wurmann

, who, already disillusioned by the war, provided a mass of information on the structure and organization of the Abwehr, as well as character assessments of its key personnel. This intelligence was rapidly disseminated throughout MI6 and the OSS. In all, some two tons of documentation were collected and shipped back to London. Most importantly, another Enigma encryption machine was captured, which proved immensely helpful to Station X at Bletchley Park in the long task of cracking the Shark U-boat cipher.