Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (47 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

As Bell explained during an interview in a documentary aired on British television in 1999, he “very much” regretted not arresting Bormann:

We were absolutely devastated and it took us a little while to get over the trauma of seeing him get away, one of the biggest; Hitler’s right-hand man to just be at liberty to board a ship and go to freedom. After all the trouble and the journey we had and the strain of having to restrain ourselves from doing something was very hard on us. And just to see that, just go away like that and not be able to do anything about it, yes, I was very upset about, I was very disheartened. But that was life, we had to get on with it, and go back to headquarters and take on another role, another brief.

Bell was asked how Bormann could have been allowed to go free and who he thought was responsible.

We were sure that the Vatican had a lot to do with Martin Bormann’s escape, because nowhere down the whole line was he ever stopped by the Carabinieri [the military force charged with police duties among civilian populations in Italy] or any army personnel; he was allowed through with complete liberty. It had been well organized. Who else could do that but the cooperation [sic] between the Vatican and the Italian government?

Martin Borman arrived in Buenos Aires on May 17, 1948, on the ship

Giovanna C

from Genoa. (Although it is not evident when or where Bormann changed ship, the

Giovanna C

was almost definitely not the same vessel that Bormann and his vehicles had boarded in Bari.)

He was dressed as a Jesuit priest, and he entered the country on a Vatican passport identifying him as the Reverend Juan Gómez. A few weeks later he registered at the Apostolic Nunciature in Buenos Aires as a stateless person and was given Identity Certificate No. 073, 909. On October 12, 1948, he was given the coveted “blue stamp” granting him permission to remain in Argentina permanently. With dreadful irony, Martin

Bormann was now known

, among other pseudonyms, by the Jewish name Eliezer Goldstein.

Bormann and the Peróns met in Buenos Aires shortly after the Reichsleiter arrived. The final negotiations over the Nazi treasure would have been heated and protracted. Documents made public in 1955 after the fall of Perón, and later in 1970, showed that the Peróns handed Bormann his promised 25 percent. The physical aspect of the treasure—outside of investments carefully structured by Ludwig Freude on behalf of his Nazi paymaster, which the Peróns had left untouched—was impressive:

187,692,400 gold marks

17,576,386 U.S. dollars

4,632,500 pounds sterling

24,976,442 Swiss francs

8,370,000 Dutch florins

54,968,000 French francs

192 pounds of platinum

2.77 tons of gold

4,638 carats of diamonds and other precious stones

Bormann’s quarter of these physical assets was still a massive fortune. Coupled with investments in over three hundred companies across the whole economic spectrum of Latin America—banks, industry, and agriculture—with Lahusen alone getting 80 million pesos—this money became “a

major factor in the economic life

of South America.”

The sailor Heinrich Bethe was present when

Bormann once again met with his Führer

at Inalco later the same year. Bormann, now disguised as “Father Augustin,” arrived wearing priest’s clothing. He was there for just over a week. On the final day of his stay, Hitler and Bormann had a private meeting that lasted almost three hours, after which he left the Center.

By the time Bormann arrived in Argentina in 1948, the world was a very different place from the one in which Col. Perón had first got involved in Aktion Feuerland with the agents of the Third Reich. The time for swastikas and defiant rallies was long over; Bormann, ever the realist, recognized that, and he would be content (once he had settled certain scores) to oversee the substantial remaining part of the looted wealth. He would be a regular visitor to the Center, but, confident of the close protection he had bought from the Peróns, he spent most of his time in Buenos Aires, where he could oil the wheels of the Organization and plan for a secure financial future.

TWO OF THE MOST IMPORTANT PLAYERS

in the Nazis’ attempted seduction of Argentina were the millionaire La Falda hoteliers Walter and Ida Eichhorn. They had been supporters and friends of the Nazi Party and Hitler since at least 1925, and Hitler would visit them—without Eva—in 1949 at La Falda.

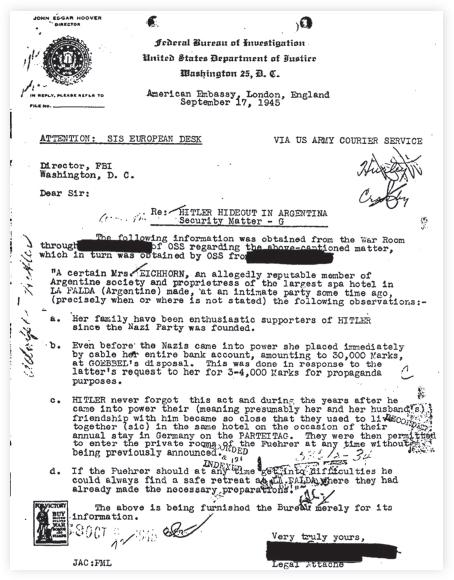

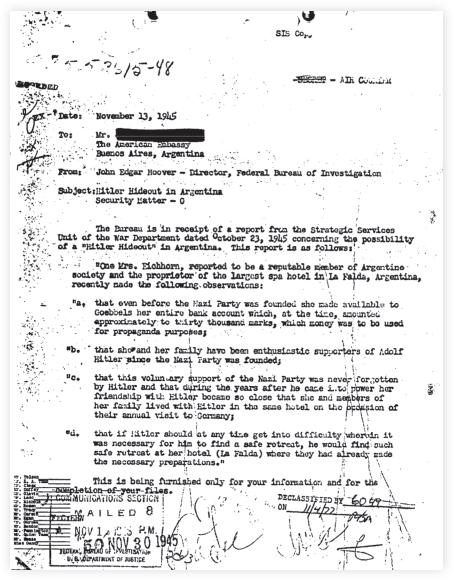

The Eichhorns first came to the attention of FBI director J. Edgar Hoover in a couriered document from the American embassy in London in September 1945. After reporting what was known of the Eichhorns’ relationship with Hitler, the document ends with a paraphrased quote from Ida Eichhorn: “if Hitler should at any time get into difficulty wherein it was necessary for him to find a safe retreat, he would find such safe retreat at her hotel (La Falda), where they had already made

the necessary preparations

.” Hoover wrote to the American Embassy in Buenos Aires several weeks later, apprising them of the situation (see

reproduction of both documents

).

The relationship between Ida Eichhorn and her “cousin,” as she always called Hitler, went back much further than 1944, though there is some dispute over the date the Eichhorns actually joined the Nazi Party. On May 11, 1935, Walter and Ida were awarded the “honor version” of the Gold Party Badge; fewer than half a dozen of the 905 such badges awarded were given to non-Reich citizens. The Führer sent the Eichhorns a personal congratulatory letter dated May 15, an unusual extra compliment accompanying the award. In the letter, which thanked Walter Eichhorn for his services, the Führer used the words “

since joining in 1924

with your wife,” which seems to indicate that the Eichhorns were among the earliest members of the party. They were also personally given No. 110 of the limited edition of 500 copies of

Mein Kampf

when they first met Hitler

at his apartment in 1925—the year the book was published.

The Eichhorns saw him again in 1927 and 1929, and thereafter they began to travel more regularly to Germany. At least one letter of Hitler’s from 1935–36 directly thanks them for a generous personal money donation. The couple were described by their grandniece Verena Ceschi as “big idealists who were really enthused by the ideas of the Führer, like all Germany at that time, [and] they became great friends.” At their luxurious

Hotel Eden

at La Falda, when Ida Eichhorn was asked if something could be accomplished, she would say anything was possible, “Adolf willing.” On her office wall there was a large photo of Hitler personally dedicated to her. There was also a room in the hotel set up as a shrine to the Führer and always decorated with freshly cut flowers. The Eden’s crockery, cutlery, and linen were stamped with the swastika, and there were many other pictures of Hitler throughout the hotel. Hitler’s speeches were captured by a shortwave antenna on the roof of the Eden and broadcast on speakers both inside and outside the hotel. The hotel had more than one hundred rooms with thirty-eight bathrooms, central heating, a huge dining and ballroom, an eighteen-hole golf course, tennis courts, a swimming pool, and many other amenities. Even today, the now semi-derelict Eden shows signs of its former magnificence, which attracted many international celebrities in the 1930s, including celebrated Jewish physicist Albert Einstein and the

Prince of Wales

. (The prince was crowned Edward VIII in January 1936, but abdicated eleven months later to marry American divorcée Wallis Simpson; as the Duke and Duchess of Windsor, both suspected Nazi sympathizers, the couple visited Hitler in 1937). It appears that Einstein may have stayed at the hotel when the anti-Semitic Eichhorns were not present.

The Eden was the meeting place for many of the Nazi organizations of Córdoba province, and military training was carried out in a camp called “Kit-Ut” on land owned by the Eichhorns. Ida also founded the

German School in La Falda

in 1940. Its primary teachers had to swear an oath of allegiance to Hitler at the German Embassy in Buenos Aires, secondary teachers had to join the National Socialist League of Teachers, and the school provided a complete program of Nazi indoctrination. This devotion to Nazism, which by 1940 applied in almost two hundred German schools in Argentina, persisted—especially in the countryside—despite a 1938 decree by President Roberto Ortiz prohibiting the exhibition of foreign flags or symbols in schools.

The schoolchildren were present at a

commemorative ceremony

held at the Eden on December 17, 1940, the first anniversary of the scuttling of the

Admiral Graf Spee.

Most of the supposedly “interned” crew marched in full uniform and paraded the Nazi flag under the eyes of dozens of Argentine dignitaries and senior members of the military. The parade ended on the hotel’s esplanade, where the Nazi Party marching song, the “Horst-Wessel-Lied,” was sung, and there were impassioned pro-German speeches. However, despite the protection of the Argentine

police and armed German sailors

who were billeted nearby, the Nazi presence in La Falda did not go completely unchallenged. When the Eichhorns decided to raise money by showing Nazi propaganda films to a large audience, members of an anti-Nazi, pro-Allies group called

Acción Argentina

punctured the tires of the parked cars of the film attendees. Among the attackers was Ernesto Guevara Lynch, father of Ernesto “Che” Guevara—the Argentine Marxist leader and Fidel Castro’s chief lieutenant of the Cuban Revolution.

AN FBI MEMO dated September 17, 1945, from the American embassy in London, outlining details of Hitler’s relationship with the Eichhorns—filed four months after the “suicide.”

A NOVEMBER 13, 1945 FBI report sent to the American embassy in Buenos Aires, recapping the September FBI report detailing the Eichhorns’ relationship with Hitler.

THE EICHORNS CONTINUED TO ORGANIZE COLLECTIONS

for the Nazi cause, and as late as 1944 they were still transferring tens of thousands of Swiss francs to the Buenos Aires account of Joseph Goebbels. However, in March 1945, under intense pressure from the United States, Argentina finally declared war on the Axis powers—the last of the Latin American nations to do so. After this declaration, the

Hotel Eden was seized

as “property of the enemy” and—now surrounded by barbed wire and guards to keep people in rather than out—used for eleven months to intern the Japanese embassy staff and their families. Shortly after the Japanese were repatriated, anti-Nazis in La Falda broke in, pulled down the eagle from the facade of the hotel, and destroyed anything with the swastika on it.

In May 1945, Ida Eichorn

told her closest circle

that her “cousin” Adolf Hitler was “traveling.” The Eichhorns, shutting themselves away in their chalet a short distance from the hotel, created a network of distribution centers that sent thousands of clothing and food parcels to a devastated Germany. They also helped the network for Nazis who fled to Argentina, and Adolf Eichmann would often visit La Falda with his family. One of his sons,

Horst Eichmann

—who led Argentina’s Frente Nacional Socialista Argentino (FNSA) Nazi party in the 1960s—married Elvira Pummer, the daughter of one of the Hotel Eden’s gardeners.

The Eichhorns maintained close contact with the Gran Hotel Viena on the shores of Mar Chiquita;

they owned a property

just 150 yards from the hotel. They would have met Hitler and Eva there while he was convalescing in 1946. (Whatever the Nazis’ long-term plans were for the Gran Hotel Viena, they never came to much. After the Hitlers’ second visit in early 1948, the property was virtually abandoned. In March of that year the

head of security, Col. Krueger

, was found “poisoned” in a room off the hotel garage—the same fate that befell Ludwig Freude four years later.)