Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (42 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

As there were no more light signals on the following nights, the whole operation was reduced to observation, and a file classified “secret,” reporting these events, was sent to the admiral in command. Bustos remembered a second incident at the end of June:

One of my soldiers found a cave almost three meters deep. We found that somebody had put three wooden shelves in the inside of the cave, ten or twenty centimeters above the high tide mark. On the shelves there were cans, the size of a beer can, without any type of identification except for one letter. The first we opened contained bread, and the next one chocolate bars. I thought the others would also have food and drinks. I then thought that this was a place to resupply either submarines or clandestine crew members who disembarked in the area. We took photos and wrote a detailed report. We took away the cans and the wood. I do not know what happened afterward to this evidence.

With hindsight, the retired colonel thought it was strange that the local press did not mention what happened, since “everybody in the area was talking about it.”

Col. Bustos was present a couple of weeks later when U-530 arrived in Mar del Plata on July 10, 1945. “When I went on board, two things caught my attention: the nasty smell in the boat (although all doors were open), and finding cans identical to the ones we had seen on the beach.”

THE GERMAN CAPABILITY TO SHIP OUT

personnel and cargo by submarines, on an ambitious scale and over long distances, certainly survived into the final weeks of the war. Intriguing proof of this was provided by

U-234

, which sailed from Kiel on March 25, 1945. This was originally built as a Type XB mine-laying boat; at 2,710 tons displacement when submerged and fully loaded, this small class of eight were the largest U-boats ever built. After suffering bomb damage during construction, U-234 was reoutfitted as a long-range cargo transporter. On this occasion—U-234’s first and only mission—its destination was Japan, and it was carrying not mines, but a dozen special passengers and 240 tons of special cargo, plus enough diesel fuel and provisions for a six- to nine-month voyage. The cargo included a crated Messerschmitt Me 262 jet fighter, a Henschel Hs 293 guided glider bomb, examples of the newest electrical torpedo guidance systems, many technical drawings, and over half a ton of uranium oxide. The passengers included Luftwaffe Gen. Ulrich Kessler, two Japanese naval officers, and civilian engineers and scientists; among the latter were Dr. Heinz Schlicke, a specialist in radar, infrared, and countermeasures who was the director of the Kriegsmarine test facility at Kiel (later recruited by the United States in Operation Paperclip), and August Bringewalde, who was in charge of Me 262 production at Messerschmitt.

The fate of U-234 would be decided by another of Martin Bormann’s “carrot and stick” deals with U.S. intelligence.

On May 1, 1945, Lt. Cdr. Johann-Heinrich Fehler opened sealed orders that instructed him to head for the east coast of the United States. He was to deliver his cargo to the U.S. Navy, but was ordered not to let some things fall into U.S. hands.

Bormann would have needed to maintain his secure communications links, so the U-boat commander threw overboard his Kurier and T43 encryption equipment and all Enigma-related documents. On May 14 the USS

Sutton

took command of U-234 and led her to the Portsmouth Navy Yard.

DOZENS OF U-BOAT SIGHTINGS

off Argentina are faithfully recorded in police and naval documents. Many of them took place within the crucial period between July 10, 1945, when the Type IXC boat U-530 surrendered at Mar del Plata, and August 17, when the Type VIIC boat U-977 surrendered at the same Argentine navy base. (U-977 allegedly took sixty-six days to cross the Atlantic, submerged all the way, and U-530 made it in sixty-three days.)

On July 21, just a week before the landing at Necochea that delivered Hitler, the Argentine navy’s chief of staff, Adm. Hector Lima, issued orders to “

Call off all coastal patrols

.” This order, from the highest echelon of the military government, effectively opened up the coast of Argentina to the landings described by the

Admiral Graf Spee

men. But despite the chase being called off by the navy, the reports of submarines off the coast kept coming in. There was a determined cover-up by highly placed members of the military government to ensure that U-530 and U-977 were the only “real” Nazi submarines seen to have made it across the Atlantic. Columnist Drew Pearson of the Bell Syndicate wrote on July 24, 1945,

Along the coast of Patagonia

, many Germans own land, which contains harbors deep enough for submarine landings. And if submarines could get to Argentine-Uruguayan waters from Germany, as they definitely did, there is no reason why they could not go a little further south to Patagonia. Also there is no reason to believe why Hitler couldn’t have been on one of them.

Speaking from exile in Rio de Janeiro in October 1945,

Raúl Damonte Taborda

—the former chair of the Argentine congressional committee on Nazi activities, and a close colleague of Silvano Santander—said that he believed it was possible Adolf Hitler was in Argentina. Damonte said that it was “indicated” that submarines other than U-530 and U-977 had been sunk by their crews after reaching the Argentine coast; these “undoubtedly” carried politicians, technicians, or even “possibly Adolf Hitler.”

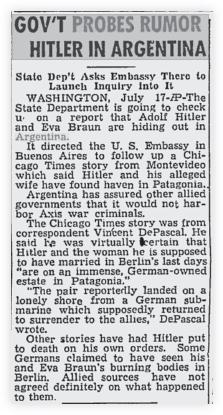

AN AP ARTICLE published in the

Lewiston Daily Sun

, July 18, 1945: One of many newspaper reports taken seriously by U.S. authorities that Hitler and Eva Braun had been landed by submarine on the Argentine coast and were living in the depths of Patagonia.

Che Guevara’s father, Ernesto Guevara Lynch, who was an active anti-Nazi “commando” in Argentina throughout the 1930s and ’40s, was also convinced: “

Not long after the German army was defeated

in Europe, many of the top Nazis arrived in our country and entered through the seaside resort of Villa Gessell, located south of Buenos Aires. They came in several German submarines.”

When asked by the authors about the submarines as recently as 2008, the Argentine justice minister, Aníbal Fernández, said simply, “In Argentina in 1945, anything was possible.”

THE EXILES STAYED JUST ONE NIGHT

at the Estancia Moromar. The first thing the couple would have done was bathe in an attempt to wash away the lingering stench of the U-boat. Fegelein had provided a selection of traveling outfits and now arranged for their old clothes to be burned. Hitler and Eva stayed in separate rooms. On the dressing table in Eva’s bedroom was her favorite perfume, Chanel No. 5; a bottle of Canadian Club whisky with an ice bucket and a tumbler; a pack of Lucky Strike cigarettes and a silver cigarette case—which Fegelein had not had time to get engraved with her distinctive “EB” monogram; and a gold Dunhill “Unique” lighter.

The grass airfield at the ranch had been laid out in 1933, shortly after Carlos Idaho Gesell had bought the property.

The next morning, July 30, 1945, Hitler, Eva, and Fegelein, accompanied by Blondi, boarded the same Argentine air force Curtiss biplane that had picked Fegelein up at Mar del Plata. They would travel the last leg of the months-long journey that had brought them nearly one-third of the way around the globe, from the rubble-strewn battlefield of Berlin to a world of huge, silent horizons.

Although Hitler had been thoroughly briefed about the vastness of Patagonia, such knowledge was theoretical, and during the daytime flight westward he was amazed at the physical spectacle unrolling below him. After what would have been a three-and-a-half-hour flight, the Curtiss Condor landed at another grass strip just outside the town of Neuquén in the north of Patagonia. None of the passengers bothered to leave the aircraft as a small tanker truck drew up, and the pilot supervised a group of men in air force uniforms while they refueled it. Topped up, the Condor was soon back in the air and heading southwest, while from the right-hand windows the three passengers watched the majestic, snow-capped Andes Mountains unrolling under the afternoon sun. Two hours later, with the waters of Lake Nahuel Huapí glinting below as dusk approached on July 30, the biplane came in to land again, bumped over the grass, and taxied to a halt on the airfield at San Ramón.

In this region, the Estancia San Ramón was the first officially delineated estate to be fenced in. The ranch is isolated, approached only via an unsurfaced road past San Carlos de Bariloche’s first airfield. The family of

Prince Stephan zu Schaumburg-Lippe

—who had been, with his ardently patriotic princess, one of the regular poker players at the German Embassy in Buenos Aires—had bought the estate as long ago as 1910 and still owned it in 1945. In 1943 Prince Stephan and Wilhelm von Schön, respectively the Nazi government’s consul and ambassador in Chile, had been called back to Germany as part of the planning for Aktion Feuerland. They left South America through Buenos Aires, where they held lengthy discussions with the de facto ambassador, the local millionaire Ludwig Freude.

A MAJOR VULNERABILITY IN THE PLAN

had been the fact that it was Adm. Wilhelm Canaris of the Abwehr who had first spotted the Estancia San Ramón, when he had used it himself as a bolt-hole during his escape across Patagonia in 1915. In 1944, when Bormann was finalizing plans for the Führer’s escape, Canaris’s knowledge of the estate, and of Villa Winter on Fuerteventura—which had been set up by his Abwehr agent Gustav Winter—was more than dangerous. Canaris—as mentioned in

Chapter 2

—was a long-time and effective conspirator against Hitler. Although Canaris had covered his tracks for years, he had still attracted suspicion from Himmler and the SS hierarchy, who, on general principles, had long wished to absorb Canaris’s military intelligence network under the Reich Main Security Office (RSHA). Canaris finally lost his ability to stay one step ahead of the SS and the Gestapo in February 1944, when two of his

Abwehr agents in Turkey

defected to the British just before the Gestapo could arrest them for links to an anti-Nazi group. Canaris failed to account for the Abwehr’s activities satisfactorily to Hitler, who had had enough of the lack of reporting to the Nazi hierarchy and instructed SS Gen. Hermann Fegelein to oversee the incorporation of the Abwehr into the RSHA. The admiral was dismissed from his post and parked in a pointless job as head of the Office for Commercial and Economic Warfare.

The involvement of Abwehr personnel in the July 20, 1944, bomb plot finally led to Canaris being placed under house arrest; the noose tightened slowly, but eventually he was being kept in chains in a cellar under Gestapo headquarters on Prinz-Albrechtstrasse in Berlin. On February 7, 1945, he was sent to Flossenbürg concentration camp, but even then he was kept alive for some time—there have been suggestions that even at this late date Himmler thought that Canaris might be useful as an intermediary with the Allies.

Bormann could not take the risk that such a potentially credible witness to the refuge in Argentina and the staging post between Europe and South America would survive to fall into Allied hands. In the Führerbunker on April 5, 1945, Bormann’s ally SS Gen. Kaltenbrunner presented Hitler with some highly incriminating evidence—supposedly, the “diaries” of Wilhelm Canaris. After reading a few pages marked for him by Kaltenbrunner, the Führer flew into a rage and signed the proffered death warrant. On the direct orders of Heinrich “Gestapo” Müller, SS Lt. Col. Walter Huppenkothen and SS Maj. Otto Thorbeck were sent to Flossenbürg to tie off this loose end. On the morning of April 9, stripped naked in a final ignominy,

Adm. Canaris was hanged

from a wooden beam. Although reports of his death vary, his end was not a quick one. At 4:33 that afternoon, Huppenkothen sent a secret Enigma-encoded message to Müller via Müller’s subordinate, SS Gen. Richard Glücks. The latter was “kindly requested” to inform SS Gen. Müller immediately, by telephone, telex, or messenger, that Huppenkothen’s mission had been completed as ordered. The only major figure who could have pieced together the details of Hitler’s escape and refuge in Argentina was dead.