Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (40 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

Inalco, Hitler’s estate in Patagonia, Argentina, looks out on Lake Nahuel Huapí, seen here with the town of Bariloche in the distance.

THE AIRFIELD AT

SAN CARLOS DE BARILOCHE

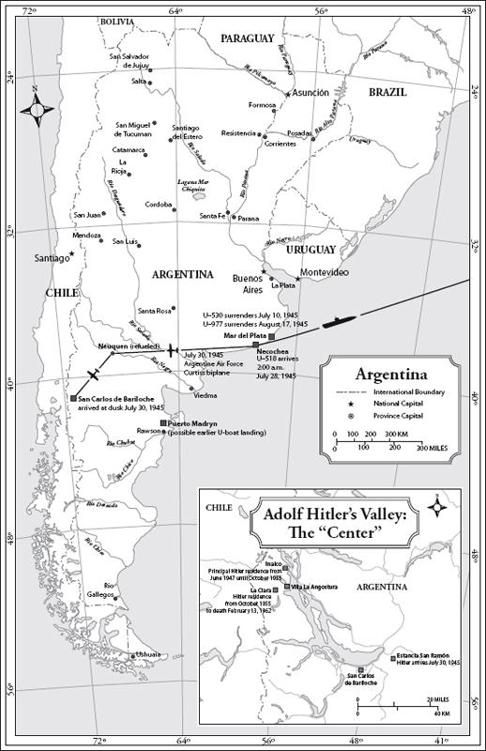

, a lakeside town in Patagonia’s Río Negro province, was opened in 1921 as part of the global boom in aviation following World War I. For the wealthy German estancia owners of Patagonia it opened up the region to commerce; the British-built railway did not arrive in the area until 1934.

The U.S. journalist Drew Pearson reported on December 15, 1943, that “Hitler’s gang has been working to build up a

place of exile

in Argentina in case of defeat. After the fall of Stalingrad and then Tunisia, they began to see defeat staring them in the face. That was their cue to move into Argentina.” The airfield had been extended and modernized during 1943 as part of the Aktion Feuerland program. This improvement made it capable of handling long-range four-engined aircraft such as the Focke-Wulf Fw 200 Condor and Junkers Ju 290, several of the options that Bormann included in his contingency planning for Hitler’s escape. The airfield was situated on the extensive lands of the Estancia San Ramón, a little over twelve miles from San Carlos de Bariloche. A dirt road led from the airfield to a large timber-built house about three miles away from the airfield, where the young Lt. Wilhelm Canaris of the German Imperial Navy had been sheltered thirty years earlier during his escape from Chile (see

Chapter 6

, and

Chapter 17

). On July 26, 1945, German sailors—a handpicked party from among the stranded crew of the

Admiral Graf Spee

—were protecting the house in expectation of important visitors.

About 650 miles to the northeast, a smaller group of

Admiral Graf Spee

men were being mustered by Capt. Walter Kay on another airfield, this one on the

Estancia Moromar near Necochea

on the Argentine coast. Carlos Idaho Gesell had bought the property, covering more than 3,200 acres, in 1932. He developed the nearby town of Villa Gesell, which he named after his father; the family was wealthy and undoubtedly had close links to the Lahusen organization. The former first officer of the

Admiral Graf Spee

,

Kay normally ran his operation

out of offices on the seventh floor of the Banco Germánico on Avenida Leandro in Buenos Aires. Kay was central to facilitating the employment—by the Nazi intelligence service in Argentina—of his supposedly “interned” sailors. The men of the

Admiral Graf Spee

had been interned by the Argentine authorities when they sought refuge after their humiliating defeat by the British Royal Navy in the Battle of the River Plate in 1939. However, the internment was at best loose, with many men simply disappearing from “captivity.” Kay—despite his interned status—had helped more than two hundred of the ship’s gunnery, communications, and other specialists to return to Germany on ships sailing under neutral flags, but he had opted to stay on in the south, where he believed he could be of more use. Kay had motivated the remaining crew, many of them committed Nazis, to regain some self-respect. Six years had been a long time to wait, but even now that the Reich had been defeated they would have a real chance to salvage something from the flames.

On July 28, 1945, three Admiral Graf Spee petty officers named Alfred Schultz, Walter Dettelmann, and Willi Brennecke were at the Estancia Moromar, equidistant between Necochea and Mar del Sur on the Argentine coast. With submachine guns slung from their shoulders, the sailors were organizing

eight trucks

to drive to the beach. The vehicles all carried Lahusen markings; five of them had been brought in by a potato farmer from his Lahusen-run property thirty-eight miles north of the Estancia Moromar, at Balcarce.

AFTER FIFTY-THREE DAYS at sea, U-518—carrying Hitler, Eva, and Blondi—arrives at Necochea on the Argentine coast. Fegelein is there to meet them. The next day the party flies to the Estancia San Ramón on the outskirts of San Carlos de Bariloche to begin their exile.

AT 1:00 A.M. ON JULY 28

,

1945

, SS Gen. Hermann Fegelein, wrapped in a borrowed greatcoat to protect him from the Argentine winter’s night, was waiting under a starlit sky on the beach at Necochea for his sister-in-law and his Führer. U-518 arrived off the coast an hour later.

Hans Offermann brought his submerged boat as close to the shore as he could, moving dead slow and with a tense hydrophone operator straining for the sounds of surface vessels; the commander had little detailed or recent information about the coastline he was approaching. Eventually he ordered the boat to periscope depth and cautiously raised the observation periscope; a careful 360-degree sweep satisfied him that no vessels or aircraft were nearby and that the light signals from shore coincided with those in his orders. Still taking no chances, he ordered his gun crews to prepare to man the 37mm and 20mm antiaircraft cannons as soon as the boat surfaced, although they had little ammunition in the lockers.

Fegelein sent out a small motorboat belonging to the ranch to meet the submarine. For the middle of the Southern Hemisphere winter, the water was surprisingly calm. As the launch approached the beach, lit by sailors’ flashlights, Fegelein raised his arm in the classic Nazi salute. The

Admiral Graf Spee

men splashed into the small breakers on the beach and helped pull the craft up onto the sand, and Fegelein moved forward to help Eva Braun from the boat. Hitler was helped down by the boat crew, returned Fegelein’s salute, and shook him by the hand.

The one-time ruler of the Thousand-Year Reich was almost unrecognizable. He was pasty-faced from the long voyage, the trademark moustache had been shaved off, and his hair was lank and uncut. Eva had made an effort to look good throughout the trip, but the prison-house pallor of her skin was highlighted by the lipstick and rouge she had applied before leaving the submarine. Of the three arrivals, Blondi probably looked the best; her excitement at being in the open air at last was controlled with the familiar red leather lead, gripped firmly in Hitler’s right hand as the party walked up the beach to a waiting car. No doubt Fegelein took the opportunity of the short drive to brief Hitler on the immediate arrangements. An avenue lined with tamarisk trees led to the main house of the Estancia Moromar, where they would spend the first night. Security at the ranch house was surprisingly light: the fewer people who knew about the visitors, the better.

The petty officers Shultz, Dettelmann, and Brennecke helped in the subsequent unloading of many heavy boxes, which were ferried ashore from the U-boat on repeated trips by the motorboat and the submarine’s rubber boats. The boxes were loaded onto the farm trucks and driven to outbuildings on the Estancia Moromar; repacked in new boxes, the contents would be taken to Buenos Aires and deposited in Nazi-controlled banks.

At the end of the unloading, most of the crew from U-518 came ashore in the rubber dinghies and marched in column in civilian clothes, their kitbags slung over their shoulders, to quarters on the estancia. Meanwhile, an eight-man skeleton crew took U-518 out on its final voyage, to be scuttled further from shore. They would return in the motorboat, to join their shipmates for their first fresh meal in two months.

They did not know that their operation had almost been compromised.

DON LUIS MARIOTTI, THE POLICE COMMISSIONER

at Necochea, had called his off-duty men in from their homes on the evening of the previous day, July 27, 1945, and ordered them to investigate unusual activity reported on the coast. The officers arrived at the beach to see an unidentified vessel offshore making Morse code signals, and they found and arrested a German who was signaling back.

Interrogated through the night

, he eventually admitted that the signaling vessel was a German submarine that wanted to put ashore at a safe place on the coast to unload.

The next morning a six-man police squad led by a senior corporal decided to comb several miles of beach north and south of the place where they had caught the signaler. After some hours, they found a stretch of sand bearing many signs of launches and dinghies being beached; heavy boxes had also been dragged toward the tire tracks of trucks. The police squad followed the tire tracks along the dirt road that led to the entrance of the Estancia Moromar. The corporal sent one of his men back to the station with his report, and then, without waiting for orders, he decided to enter the farm. The five police officers had walked a couple of miles in along the tree-lined drive when they came to some low hills, which hid the main buildings. Four Germans carrying submachine guns challenged them. The corporal had no search warrant and was seriously outgunned; he decided to withdraw and report back to his superior.

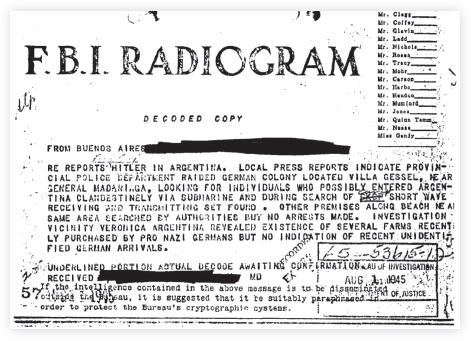

Commissioner Mariotti telephoned the chief of police

at La Plata. The call was taken by the latter’s secretary, who told him to do nothing and remain by the telephone. Two hours later Don Luis was ordered to forget the matter and release the arrested German. The following month an

FBI message

from Buenos Aires stated: “Local Press reports indicate provincial police department raided German colony located Villa Gesell … looking for individuals who possibly entered Argentina clandestinely via submarine and during search a short-wave … [illegible] receiving and transmitting set found. Other premises along beach near same area searched by authorities but no arrests made.”