Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler (38 page)

Read Grey Wolf: The Escape of Adolf Hitler Online

Authors: Simon Dunstan,Gerrard Williams

Tags: #Europe, #World War II, #ebook, #General, #Germany, #Military, #Heads of State, #Biography, #History

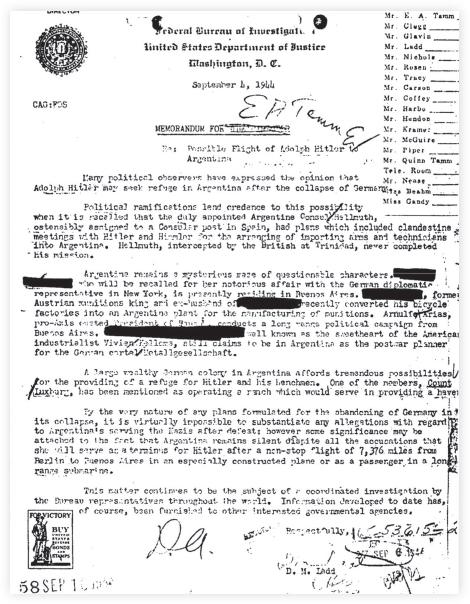

AN FBI DOCUMENT from 1944 details where Hitler would find refuge in Argentina if he lost the war.

MUCH OF THE CREDIT FOR EXPOSING

Nazi links with leading Argentine figures belongs to the one-time Radical Party deputy for the province of Entre Ríos, Silvano Santander. This dedicated anti-Nazi had worked with Raúl Damonte Taborda since 1939, and in 1944 their refusal to be silenced led to a warrant for their arrest, obliging them both to flee the country. Santander went only as far as Montevideo in Uruguay, just across the Río del Plata from Buenos Aires, where he continued to work

tirelessly in exile

. In November 1952, he and his team traveled to West Germany, following a tip-off about a mass of documentation uncovered by the war crimes commission in Berlin during its hunt for Nazi links with Argentina.

Santander subsequently published

two books about the background of the Peróns’ rise to become Argentina’s first couple; his work was based on the documents he had studied in Berlin, which had been authenticated by U.S. Department of State foreign service investigator William Sidney and Herbert Sorter, chief of the External Assets Investigation Branch in the U.S. High Commissioner’s Office.

Among the documents were confidential reports about diplomats and Nazi agents, sent from South America to Bormann, Foreign Minister

Joachim von Ribbentrop

, and the spymaster Gen. von Faupel. Among them were handwritten memos that had passed between Bormann and the German ambassador in Buenos Aires, Baron Edmund von Thermann (who, unsurprisingly, held the rank of SS major). In one such memo, Ambassador von Thermann praised the Buenos Aires government as loyal supporters of Nazism and pointed out that the Buenos Aires provincial governor from 1936 to 1940, Dr. Manuel A. Fresco, had installed on his ranch, Estancia Monasterio, “a powerful radio transceiver by which they had a permanent communication system” between Argentina and Germany. This would be a crucial link in Bormann’s plans for Hitler’s escape, allowing for the likely use by Ludwig Freude of a

Siemens & Haske T43 encryption machine

that would have been delivered to Buenos Aires in 1944.

AS EARLY AS MAY 1940

, many of the Nazis’ Argentine supporters would gather regularly for friendly games of poker at the German embassy in Buenos Aires. The German players included Ambassador von Thermann; Prince Stephan zu Schaumburg-Lippe, a consular officer based in Chile; the naval attaché Capt. Dietrich Niebuhr; the press attaché Gottfried Sandstede; Ricardo von Leute, the general manager of Lahusen; and the multimillionaire banker Ludwig Freude. On the other side of the dealer, the Argentine players included various military and naval officers: Generals von der Becke, Pertiné, Ramírez, and Farrell, and Colonels Perón, Brickman, Heblin, Mittelbach, Tauber, Gilbert, and Gonzalez (the number of German family names is striking). Occasionally Carlos Ibarguren, head of the legal department of the Banco de la Nación, and Miguel Viancarlos, chief of investigations for the Argentine police, would also sit in. The Nazis were “useless” at poker and lost heavily. Allied intelligence reported that the Argentines would leave with smiles on their faces, remarking how innocent their German opponents were, but Thermann would later tell the Allied war crimes commission, “We wanted to make our friends happy—

we always let them win

.”

Press attaché Gottfried Sandstede had two other roles: he was also an employee of the

Delfino shipping

line and Gen. von Faupel’s personal representative. The FBI suspected that Delfino SA was heavily involved in Bormann’s shipments of loot from Europe, at first by surface vessel and aircraft and later by submarine. On September 8, 1941,

Time

magazine reported:

In the three months since thirty-two-year-old Deputy Raúl Damonte Taborda began a [congressional] investigation of anti-Argentine activities he has stealthily and steadily crept closer to Argentina’s cuckoo nest: the German Embassy. Last week Deputy Damonte thought he had his hands on the biggest cuckoo in the nest.

The bird he was after was not Ambassador von Thermann, but Gottfried Sandstede. Damonte believed that Sandstede was the senior Nazi spy in Argentina and that Thermann actually took instructions from him—a suspicion that Thermann would later verify.

When Damonte came after him, Sandstede claimed diplomatic immunity, but, as an employee of Delfino, he was denied this status by the Argentine Foreign Ministry. Somebody tipped off the German embassy about Sandstede’s imminent arrest, giving him time to arrange his urgent departure. Police were posted outside his house and the German embassy and at checkpoints along the roads leading from the city to the airport. One of these pickets stopped a suspicious-looking car that tried to pass through the cordon, and arrested Karl Sandstede, the fugitive’s brother. Believing they had the wanted man, the police relaxed the cordon, and early the next morning Gottfried Sandstede boarded a plane for Brazil at Buenos Aires airport. Upon Sandstede’s arrival in Rio de Janeiro, Ambassador von Thermann “announced blandly that Herr Sandstede had been

recalled to Berlin

to report on anti-German activities in Argentina.”

The truth was more interesting. On the morning of the escape, the Kriegsmarine attaché, Capt. Niebuhr, wrote to Gen. von Faupel, “We had to send our press attaché Gottfried Sandstede from the country in haste. We received information from our Miss Eva Duarté, an Argentinean who is always excellently informed.” The actress was more than simply an informant, however; she had played an active part in the escape by turning up at the German embassy in Col. Perón’s War Ministry staff car with an Argentine military uniform complete with greatcoat and cap: a disguise for Sandstede. Thus disguised as a senior Argentine military officer, with a stunning blonde beside him, Sandstede was

simply waved through

the police cordon. Three days after Sandstede’s flight, Deputy Damonte submitted to the Argentine congress a report by his investigative committee. Among its major conclusions, the report stated that, despite its official dissolution in May 1939, the Argentine Nazi Party continued to operate cells throughout the country, organized on military lines, and that the German embassy participated directly in the party’s activities.

The papers studied by Santander in 1952 revealed that Eva Duarté would soon

enjoy the trust of the Nazi agents

to a remarkable degree. When Niebuhr himself had to leave the country after being “outed” for espionage activities, he wrote to von Faupel, “Luckily, with some exceptions, they did not have news of our most important staff or of our contacts.” Niebuhr reported that he was actually passing over responsibility for parts of the Nazi network in the “Brazil and South Pacific [southern Chile] sections” to Duarté, whom he described as “a devilishly beautiful, intelligent, charming, ambitious, and unscrupulous woman, who has already caught the eye of Colonel Perón.”

Three months after the flight of Gottfried Sandstede, the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor brought the United States into World War II. In January 1942, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s government summoned a conference of all the nations of the Americas to meet in Rio de Janeiro. The State Department exerted pressure on all Western Hemisphere countries to cut diplomatic relations with Japan, Germany, and Italy. Within two weeks, on January 28, all but two of the twenty-one republics announced their agreement; those that refused were Chile and Argentina. Despite the

revelations

of the

Damonte report

, it would be October 23, 1942, before Ambassador von Thermann left Buenos Aires for good. His practical functions passed, unofficially but unequivocally, to the banker and industrialist Ludwig Freude.

IN APRIL 1943

,

WHEN THE TIDE OF WAR

was obviously beginning to turn in the Allies’ favor,

von Faupel

traveled to Buenos Aires in person by U-boat. He was accompanied by Sandstede, who had not returned to the country since he had been spirited out with Eva Duarté’s help in September 1941. When they arrived on May 2, they were received by Argentina’s outspokenly pro-fascist and anti-American navy minister, Adm. Leon

Scasso

. Von Faupel stayed in the German evangelist church on Calle Esmeralda in Buenos Aires. Before they departed on May 8, they held meetings with—among others—Ludwig Freude, Ricardo von Leute of the Lahusen company, and Col. Perón and Eva Duarté. Thermann would later tell the war crimes commission that “the real motive for Faupel’s visit was to make Argentina a safe place for the future, in the certainty of defeat.”

Von Faupel told Perón that it was now possible that Germany would lose the war. In that case, he warned, Perón and his friends were going to end up facing charges of high treason. The Nazi spymaster told his Argentine contacts that there was only one way to avoid this: they had to seize power and “

maintain it at all costs

.” It would take less than a month for them to act on his advice.

On June 4, 1943, Gen. Arturo Rawson and the Grupo de Oficiales Unidos (United Officer’s Group, or GOU)—a secret clique of senior military officers in which Col. Perón played a significant part—launched a coup d’état. It took about half a day to overthrow the three-year-old regime of Argentina’s conservative president, Ramón S. Castillo; Rawson himself would preside for less than two days, however, before being replaced by Gen. Pedro Pablo Ramírez. Germany, Italy, and the U.S. State Department immediately recognized the new regime; the United States hoped that Argentina would finally give up its neutrality and join the fight against the Axis. The precedent of the authoritarian Getúlio Vargas regime in Brazil, which had joined the Allies in August 1942, was encouraging. However, the new Argentine government proved even less cooperative than the old one. Ramírez was president in name only; the real power lay with the GOU, known simply as “the Colonels,” and well placed among them was Juan Domingo Perón. (One of the GOU’s early acts was to close down Deputy Damonte’s committee of enquiry into Nazi activities.) Perón became an assistant to the secretary of war and, a short time later, the head of the Department of Labor. This then-insignificant ministry would provide him with an unsuspected power base.

At the German embassy, Capt. Niebuhr’s replacement in the Nazi network was Erich Otto Meynen (another of the poker players), and he could hardly contain his triumph when he wrote to his predecessor: “I have spent day and night traveling or receiving Party members; they come from all parts of the country to see me. My efforts have not been in vain. The success of our friends’ revolution has been complete.” Eva Duarté had shown

Meynen

a letter that outlined Perón’s political philosophy: “The Argentine workers were born animals of the herd, and they will die as such. To rule them it is enough to give them food, work, and laws to follow, which will keep them in line.” Niebuhr thought Perón followed “the good school.”

AMERICAN ANGER AT ARGENTINA’S REFUSAL

to curb Nazi activities, and at the Ramírez government’s stubborn maintenance of an ostensible neutrality in the war, came to a head with the publication of a blistering exchange of letters between Argentine foreign minister Adm. Segundo Storni and U.S. secretary of state Cordell Hull in September 1943. The row was deliberately made public by the United States, causing a storm in Buenos Aires; Storni resigned, and anti-American feeling blossomed in Argentina. The press reported one typical young “hothead” as declaring, “

To hell with the U.S.

We’re looking toward Europe, for now and after the war.”

Continuing American pressure only made the Colonels more popular, but then Great Britain and the United States threatened to go public with detailed information on the Nazis’ links with members of the Argentine government—which would lead to global ostracization of Argentina. In January 1944, President Ramírez, folding under this threat, suspended diplomatic relations with Germany and Japan. (Italy had already surrendered to the Allies on September 8, 1943.)

The GOU immediately replaced Ramírez with his fellow poker player Gen. Edelmiro J. Farrell. Perón became vice president and secretary of war, while retaining his labor portfolio. His work in this ministry helped him to forge an alliance with the Argentine labor unions; together they put forward laws that strengthened the unions and improved workers’ rights. Against intuition, the military conspirator Perón increasingly became the voice of the working people, and now he was just one step from the presidency.

PERÓN’S PUBLIC RELATIONS BREAKTHROUGH

followed the devastating earthquake that hit San Juan on January 15, 1944, which claimed over 10,000 lives and leveled the central-western Argentine city.

Vice President Perón moved into overdrive

; he was entrusted with fund-raising efforts and enlisted media celebrities to help. His work made a real difference in the region’s recovery and gained him great popular support. This was also the perfect time for his relationship with Eva Duarté to be revealed to the public. Accepted history tells us that Perón met the young radio star at one of his fund-raising events in May 1944; in reality, as we have seen, their working and romantic relationship went back considerably further. It was at this time that Eva’s public profile was created—as a girl from humble beginnings who used her achievement of stardom and social connections to work for the interests of the poor among whom she had grown up. It was a perception that fit neatly alongside Col. Perón’s pose as a defender of workers’ rights. This image of a beautiful, glittering champion of the poor—los descamisados (the “shirtless ones”)—would earn “Evita” unparalleled public affection, and indeed a sort of secular sainthood, which would endure in the hearts of many Argentines for generations after her death.