Grit (11 page)

Authors: Angela Duckworth

I thought about how important it is to know how low-level goals fit into one’s overall hierarchy when I listened to Roz Chast, the celebrated

New Yorker

cartoonist, give a talk at the local library. She told us her rejection rate is, at this stage in her career, about 90 percent. She claimed that it used to be much, much higher.

I called Bob Mankoff, the cartoon editor for the

New Yorker

, to ask how typical that number is. To me, it seemed shockingly high. Bob told me that Roz was indeed an anomaly.

Phew!

I thought. I didn’t want to think about all the cartoonists in the world getting rejected nine times out of ten. But then Bob told me that most cartoonists live with

even more

rejection. At his magazine, “contract cartoonists,” who have dramatically better odds of getting published than anyone else, collectively submit about five hundred cartoons every week. In a given issue, there is only room, on average, for about seventeen of them. I did the math: that’s a rejection rate of more than 96 percent.

“Holy smokes! Who would keep going when the odds are that grim?”

Well, for one: Bob himself.

Bob’s story reveals a lot about how dogged perseverance toward a top-level goal requires, paradoxically perhaps, some flexibility at lower levels in the goal hierarchy. It’s as if the highest-level goal gets written in ink, once you’ve done enough living and reflecting to know what that goal is, and the lower-level goals get written in pencil, so you can revise them and sometimes erase them altogether, and then figure out new ones to take their place.

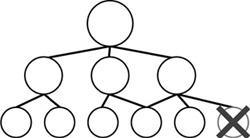

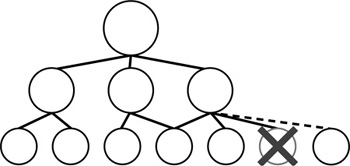

Here’s my not-at-all-

New Yorker

–quality drawing to show what I mean:

The low-level goal with the angry-looking X through it has been blocked. It’s a rejection slip, a setback, a dead end, a failure. The gritty person will be disappointed, or even heartbroken, but not for long.

Soon enough, the gritty person identifies a new low-level goal—draws another cartoon, for example—that serves the same purpose.

One of the mottos of the Green Berets is:

“Improvise, adapt, overcome.” A lot of us were told as children, “If at first you don’t succeed, try, try again.” Sound advice, but as they say “try, try again, then try something different.” At lower levels of a goal hierarchy, that’s exactly what’s needed.

Here’s Bob Mankoff’s story:

Like Jeff Gettleman, the

New York Times

East Africa bureau chief, Bob didn’t always have a clearly defined passion. As a child, Bob liked to draw, and instead of attending his local high school in the Bronx, he went to the LaGuardia High School of Music and Art, later fictionalized in the movie

Fame

.

Once there, though, he got a look at the competition and was intimidated.

“Being exposed to real drawing talent,” Bob recalls,

“made mine wither. I didn’t touch a pen, pencil, or paintbrush for three years after graduating.” Instead, he enrolled at Syracuse University, where he studied philosophy and psychology.

In his senior year, he bought a book called

Learning to Cartoon

by the legendary Syd Hoff, an exemplar of the “effort counts twice” maxim. Over his lifetime, Hoff contributed 571 cartoons to the

New Yorker

, wrote and illustrated more than sixty children’s books, drew two syndicated comic strips, and contributed literally thousands of drawings and cartoons to other publications. Hoff’s book opens cheerily with “Is it hard becoming a cartoonist? No, it isn’t. And to prove it,

I’ve written this book. . . .” It ends with a chapter called “How to Survive Rejection Slips.” In between are lessons on composition, perspective, the human figure, facial expressions, and so on.

Bob used Hoff’s advice to create twenty-seven cartoons. He walked from one magazine to another, trying to make a sale—but not the

New Yorker

, which didn’t see cartoonists in person. And he was, of course, summarily rejected by every editor he saw. Most asked him to try again, with more cartoons, the next week. “More?” Bob wondered.

“How could anyone do more than twenty-seven cartoons?”

Before he could reread Hoff’s last chapter on rejection slips, Bob received notice that he was eligible to be drafted for combat in Vietnam. He had no great desire to go; in fact, he had a great desire

not

to. So he repurposed himself—quickly—as a graduate student in experimental psychology. Over the next few years, while running rats in mazes, he found time, when he could, to draw. Then, just before earning his doctorate, he had the realization that research psychology wasn’t his calling: “I remember thinking that my defining personality characteristic was something else.

I’m the funniest guy you ever met—that’s the way I thought of myself—I’m

funny

.”

For a while, Bob considered two ways of making humor his career: “I said, okay, I’m going to do stand-up, or

I’m going to be a cartoonist.” He threw himself into both with gusto: “All day I would write routines and then, at night, I would draw cartoons.” But over time, one of these two mid-level goals became more attractive than the other: “Stand-up was different back then. There weren’t really comedy clubs. I’d have to go to the Borscht Belt, and I didn’t really want to. . . . I knew my humor was not going to work like I wanted it to for these people.”

So Bob dropped stand-up comedy and devoted his entire energy to cartoons. “After two years of submitting, all I had to show for it were enough

New Yorker

rejection slips to

wallpaper my bathroom.” There were small victories—cartoons sold to other magazines—but by that time Bob’s top-level goal had become a whole lot more specific and ambitious: He didn’t just want to be funny for a living, he wanted to be among the best cartoonists in the world. “The

New Yorker

was to cartooning what the New York Yankees were to baseball—the Best Team,” Bob explains. “If you could make that team,

you too were one of the best.”

The piles of rejection slips suggested to Bob that “try, try again” was not working. He decided to do something different. “I went to the New York Public Library and

I looked up all the cartoons back to 1925 that had ever been printed in the

New Yorker

.” At first, he thought maybe he didn’t draw well enough, but it was plain to see that some very successful

New Yorker

cartoonists were third-rate draftsmen. Then Bob thought that something might be awry with the length of his captions—too short or too long—but that possibility wasn’t supported, either. Captions were generally brief, but not always, and anyway, Bob’s didn’t seem unusual in that respect. Then Bob thought maybe he was missing the mark with his

type

of humor. No again: some successful cartoons were whimsical, some satirical, some philosophical, and some just interesting.

The one thing all the cartoons had in common was this: they made the reader

think

.

And here was another common thread: every cartoonist had a personal style that was distinctively their own. There was no single “best” style. On the contrary, what mattered was that style was, in some very deep and idiosyncratic way, an expression of the individual cartoonist.

Paging through, literally, every cartoon the

New Yorker

had ever published, Bob knew he could do as well. Or better. “I thought, ‘I can do this, I can do this.’

I had complete confidence.” He knew he could draw cartoons that would make people think, and he knew he could develop his own style: “I worked through various styles. Eventually I did my dot style.” The now-famous dot style of Bob’s cartoons is called stippling, and Bob had originally tried it out back in high school, when he discovered the French impressionist Georges Seurat.

After getting rejected from the

New Yorker

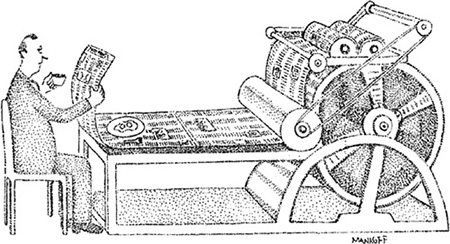

about two thousand times between 1974 and 1977, Bob sent in the cartoon, below. It was accepted.

Robert Mankoff, the

New Yorker

, June 20, 1977, The

New Yorker

Collection/The Cartoon Bank.

The next year, he sold thirteen cartoons to the

New Yorker

, then twenty-five the following year, then twenty-seven. In 1981, Bob received a letter from the magazine asking if he’d consider becoming a contract cartoonist. He said yes.

In his role as editor and mentor, Bob advises aspiring cartoonists to submit their drawings in batches of ten, “because in cartooning, as in life, nine out of ten

things never work out.”

Indeed, giving up on lower-level goals is not only forgivable, it’s sometimes absolutely necessary. You should give up when one lower-level goal can be swapped for another that is more feasible. It also makes sense to switch your path when a different lower-level goal—a different means to the same end—is just more efficient, or more fun, or for whatever reason makes more sense than your original plan.

On any long journey, detours are to be expected.

However, the higher-level the goal, the more it makes sense to be stubborn. Personally, I try not to get too hung up on a particular rejected grant application, academic paper, or failed experiment. The pain of those failures is real, but I don’t dwell on them for long before moving on. In contrast, I don’t give up as easily on mid-level goals, and frankly, I can’t imagine anything that would change my ultimate aim, my life philosophy, as Pete might say. My compass, once I found all the parts and put it together, keeps pointing me in the same direction, week after month after year.

Long before I conducted the first interviews that put me on the trail of grit, a Stanford psychologist named Catharine Cox was, herself, cataloging the characteristics of high achievers.

In 1926, Cox published her findings, based on the biographical details of

301 exceptionally accomplished historical figures. These eminent individuals included poets, political and religious leaders, scientists, soldiers, philosophers, artists, and musicians. All lived and died in the four centuries prior to Cox’s investigation, and all left behind

records of accomplishment worthy of documentation in six popular encyclopedias.

Cox’s initial goal was to estimate how smart each of these individuals were, both relative to one another and also compared to the rest of humanity. In pursuit of those estimates, she combed through the available evidence, searching for signs of intellectual precocity—and from the age and superiority of these accomplishments she reckoned each person’s childhood IQ. The published summary of this study—if you can call a book of more than eight hundred pages a summary—includes a case history for each of Cox’s 301, arranged in order from least to most intelligent.

According to Cox, the very smartest in the bunch was the philosopher John Stuart Mill, who earned an estimated childhood IQ score of 190 by learning Greek at age three, writing a history of Rome at age six, and assisting his father in correcting the proofs of a history of India at age twelve. The least intelligent in Cox’s ranking—whose estimated childhood IQs of 100 to 110 are just a hair above average for humanity—included the founder of modern astronomy, Nicolaus Copernicus; the chemist and physicist Michael Faraday; and the Spanish poet and novelist Miguel de Cervantes. Isaac Newton ranks squarely in the middle, with an IQ of 130—the bare minimum that a child needs in order to qualify for many of today’s gifted and talented programs.