Grit (7 page)

Authors: Angela Duckworth

In other words, mythologizing natural talent lets us all off the hook. It lets us relax into the status quo. That’s what undoubtedly occurred in my early days of teaching when I mistakenly equated talent and achievement, and by doing so, removed effort—both my students’ and my own—from further consideration.

So what is the reality of greatness? Nietzsche came to the same conclusion Dan Chambliss did. Great things are accomplished by those “people whose thinking is

active in

one

direction, who employ everything

as material, who always zealously observe their own inner life and that of others, who perceive everywhere models and incentives, who never tire of combining together the means available to them.”

And what about talent? Nietzsche implored us to consider exemplars to be, above all else, craftsmen: “Do not talk about

giftedness, inborn talents! One can name great men of all kinds who were very little gifted. They

acquired

greatness, became ‘geniuses’ (as we put it). . . . They all possessed that seriousness of the efficient workman which first learns to construct the parts properly before it ventures to fashion a great whole; they allowed themselves time for it, because they took more pleasure in making the little, secondary things well than in the effect of a dazzling whole.”

In my second year of graduate school, I sat down to a weekly meeting with my advisor, Marty Seligman. I was more than a little nervous. Marty has that effect on people, especially his students.

Then in his sixties, Marty had won just about every accolade psychology has to offer. His early research led to an unprecedented understanding of clinical depression. More recently, as president of the American Psychological Association, he christened the field of Positive Psychology, a discipline that applies the scientific method to questions of

human flourishing.

Marty is barrel-chested and baritone-voiced. He may study happiness and well-being, but

cheerful

is not a word I’d use to describe him.

In the middle of whatever it was I was saying—a report on what I’d done in the past week, I suppose, or the next steps in one of our research studies—Marty interrupted. “You haven’t had a good idea in two years.”

I stared at him, openmouthed, trying to process what he’d just said. Then I blinked. Two years? I hadn’t even been in graduate school for two years!

Silence.

Then he crossed his arms, frowned, and said: “You can do all kinds of fancy statistics. You somehow get every parent in a school to return their consent form. You’ve made a few insightful observations. But you don’t have a theory. You don’t have a theory for the psychology of achievement.”

Silence.

“What’s a theory?” I finally asked, having absolutely no clue as to what he was talking about.

Silence.

“Stop reading so much and go think.”

I left his office, went into mine, and cried. At home with my husband, I cried more. I cursed Marty under my breath—and aloud as well—for being such a jerk. Why was he telling me what I was doing wrong? Why wasn’t he praising me for what I was doing right?

You don’t have a theory. . . .

Those words rattled around in my mind for days. Finally, I dried my tears, stopped my cursing, and sat down at my computer. I opened the word processor and stared at the blinking cursor, realizing I hadn’t gotten far beyond the basic observation that talent was not enough to succeed in life. I hadn’t worked out how, exactly, talent and effort and skill and achievement all fit together.

A theory is an explanation. A theory takes a blizzard of facts and observations and explains, in the most basic terms, what the heck is going on. By necessity, a theory is incomplete. It oversimplifies. But in doing so, it helps us understand.

If talent falls short of explaining achievement, what’s missing?

I have been working on a theory of the psychology of achievement since Marty scolded me for not having one. I have pages and pages of diagrams, filling more than a dozen lab notebooks. After more than a

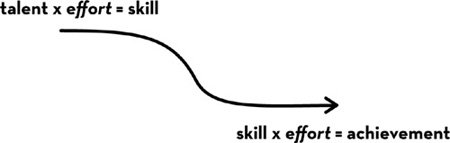

decade of thinking about it, sometimes alone, and sometimes in partnership with close colleagues, I finally published an article in which I lay down two simple equations that explain how you get from talent to achievement.

Here they are:

Talent is how quickly your skills improve when you invest effort. Achievement is what happens when you take your acquired skills and use them. Of course, your opportunities—for example, having a great coach or teacher—matter tremendously, too, and maybe more than anything about the individual. My theory doesn’t address these outside forces, nor does it include luck. It’s about the psychology of achievement, but because psychology isn’t all that matters, it’s incomplete.

Still, I think it’s useful. What this theory says is that when you consider individuals in identical circumstances, what each achieves depends on just two things, talent and effort. Talent—how fast we improve in skill—absolutely matters. But effort factors into the calculations

twice

, not once. Effort builds skill. At the very same time, effort makes skill

productive

. Let me give you a few examples.

There’s a celebrated potter named Warren MacKenzie who lives in Minnesota. Now ninety-two years old, he has been at his craft, without interruption, for nearly his entire adult life. Early on, he and his

late wife, also an artist, tried a lot of different things: “You know, when you’re young, you think you can do anything, and we thought, oh, we’ll be potters, we’ll be painters, we’ll be textile designers, we’ll be jewelers, we’ll be a little of this, a little of that. We were

going to be the renaissance people.”

It soon became clear that doing one thing better and better might be more satisfying than staying an amateur at many different things: “Eventually both of us gave up the drawing and painting, gave up the silk-screening, gave up the textile design, and concentrated on ceramic work, because that was where we felt

our true interest lay.”

MacKenzie told me “a good potter can make

forty or fifty pots in a day.” Out of these, “some of them are good and some of them are mediocre and some of them are bad.” Only a few will be worth selling, and of those, even fewer “will

continue to engage the senses after daily use.”

Of course, it’s not just the number of good pots MacKenzie makes that has brought the art world to his door. It’s the beauty and form of the pots: “I’m striving to make things which are

the most exciting things I can make that will fit in people’s homes.” Still, as a simplification, you might say that the number of enduringly beautiful, exquisitely useful pots MacKenzie is able to produce, in total, will be what he accomplishes as an artist. It would not satisfy him to be among the most masterful potters but only produce, say, one or two pieces in his lifetime.

MacKenzie still throws clay on the wheel every day, and with effort his skill has improved: “I think back to some of the pots we made when we first started our pottery, and they were pretty awful pots. We thought at the time they were good; they were the best we could make, but our thinking was so elemental that the pots had that quality also, and so they don’t have a richness about them which I look for

in my work today.”

“The

first 10,000 pots are difficult,” he has said, “and then it gets a little bit easier.”

As things got easier, and as MacKenzie improved, he produced more good pots a day:

talent x

effort

= skill

At the same time, the number of good pots he’s brought into the world increased:

skill x

effort

= achievement

With effort, MacKenzie has gotten better and better at making “the most exciting things I can make that will fit in people’s homes.” At the same time, with the same invested effort, he has become more accomplished.

“

Garp was a natural storyteller.”

This is a line from John Irving’s fourth novel,

The World According to Garp

. Like that novel’s fictional protagonist, Irving tells a great story. He has been lauded as “

the great storyteller of American literature today.” To date, he’s written more than a dozen novels, most of which have been best sellers and half of which have been made into movies.

The World According to Garp

won the National Book Award, and Irving’s screenplay for

The Cider House Rules

won an Academy Award.

But unlike Garp, Irving was not a natural. While

Garp “could make things up, one right after the other, and they seemed to fit,” Irving rewrites draft after draft of his novels. Of his early attempts at writing, Irving has said, “Most of all, I rewrote everything . . . I began to take

my lack of talent seriously.”

Irving recalls earning a C– in high school English. His

SAT verbal score was 475 out of 800, which means almost two-thirds of the students who took the SAT did better than him. He needed to stay in high

school an extra year to have enough credits to graduate. Irving recalls that his teachers thought he was both

“lazy” and “stupid.”

Irving was neither lazy nor stupid. But he was severely dyslexic: “I was an underdog. . . . If my classmates could read our history assignment in an hour, I allowed myself two or three. If I couldn’t learn to spell, I would keep a list of my most

frequently misspelled words.” When his own son was diagnosed with dyslexia, Irving finally understood why he, himself, had been such a poor student. Irving’s son read noticeably slower than his classmates, “with his finger following the sentence—as I read, as I

still

read. Unless I’ve written it, I read whatever ‘it’ is very

slowly—and with my finger.”

Since reading and writing didn’t come easily, Irving learned that “to do anything really well,

you have to overextend yourself. . . . In my case, I learned that I just had to pay twice as much attention. I came to appreciate that in doing something over and over again, something that was never natural becomes almost second nature. You learn that you have the capacity for that, and that it doesn’t come overnight.”

Do the precociously talented learn that lesson? Do they discover that the capacity to do something over and over again, to struggle, to have patience, can be mastered—but not overnight?

Some might. But those who struggle early may learn it better: “One reason I have confidence in writing the kind of novels I write,” Irving said, “is that I have confidence in my stamina to go over something again and again

no matter how difficult it is.” After his tenth novel, Irving observed,

“Rewriting is what I do best as a writer. I spend more time revising a novel or screenplay than I take to write the first draft.”

“It’s become an advantage,” Irving has observed of his inability to read and spell as fluently as others. “In writing a novel, it doesn’t hurt anybody

to have to go slowly. It doesn’t hurt anyone as a writer to have to go over something again and again.”

With daily effort, Irving became one of the most masterful and prolific

writers in history. With effort, he became a master, and with effort, his mastery produced stories that have touched millions of people, including me.

Grammy Award–winning musician and Oscar-nominated actor Will Smith has thought a lot about talent, effort, skill, and achievement. “I’ve never really viewed myself as particularly talented,” he once observed. “Where I excel is ridiculous,

sickening work ethic.”

Accomplishment, in Will’s eyes, is very much about going the distance. Asked to explain his ascendancy to the entertainment elite, Will said:

The only thing that I see that is distinctly different about me is: I’m not afraid to die on a treadmill. I will not be outworked, period. You might have more talent than me, you might be smarter than me, you might be sexier than me. You might be all of those things. You got it on me in nine categories. But if we get on the treadmill together, there’s two things: You’re getting off first,

or I’m going to die. It’s really that simple.

In 1940, researchers at Harvard University had the same idea. In a study designed to understand the “characteristics of

healthy young men” in order to “help people live happier, more successful lives,” 130 sophomores were asked to run on a treadmill for up to five minutes. The treadmill was set at such a steep angle and cranked up to such a fast speed that the average man held on

for only four minutes. Some lasted for only a minute and a half.

By design, the Treadmill Test was exhausting. Not just physically but mentally. By measuring and then adjusting for baseline physical fitness, the researchers designed the Treadmill Test to gauge “stamina

and

strength of will.” In particular, Harvard researchers knew that running hard was not just a function of aerobic capacity and muscle strength but also the extent to which “a subject is willing to push himself or has a tendency to quit before the punishment

becomes too severe.”

Decades later, a psychiatrist named George Vaillant followed up on the young men in the original Treadmill Test. Then in their sixties, these men had been contacted by researchers every two years since graduating from college, and for each there was a corresponding file folder at Harvard literally bursting with questionnaires, correspondence, and notes from in-depth interviews. For instance, researchers noted for each man his income, career advancement, sick days, social activities, self-reported satisfaction with work and marriage, visits to psychiatrists, and use of mood-altering drugs like tranquilizers. All this information went into composite estimates of the men’s overall psychological adjustment in adulthood.