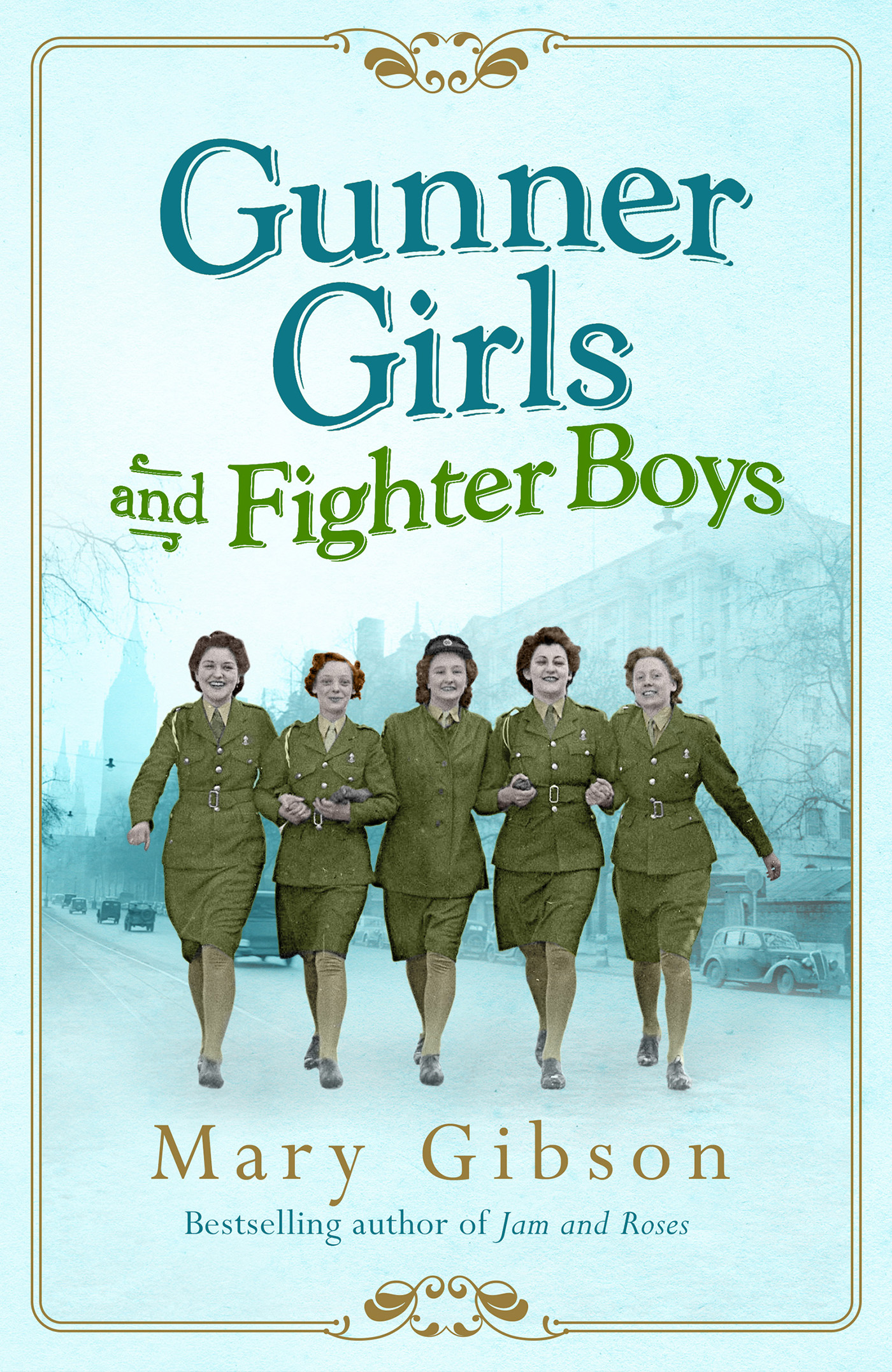

Gunner Girls and Fighter Boys

Read Gunner Girls and Fighter Boys Online

Authors: Mary Gibson

About

Gunner Girls and Fighter Boys

About The Factory Girls Series

Dedicated to the memory of my parents Mary and Bill Gibson, whose service in the ATS and RAF during the Second World War was my inspiration.

Chapter 5: Predicting the Future

Chapter 14: No Taste in Nothing

Chapter 15: Engaging the Enemy

Chapter 20: Gold and Pleasant Land

Chapter 23: The Land of Begin Again

Chapter 24: ‘I’m Looking For An Angel’

Chapter 25: ‘Always Together, Whatever the Weather’

Chapter 26: ‘Tomorrow is a Lovely Day’

Chapter 33: The World That Was Ours

About

Gunner Girls and Fighter Boys

About The Factory Girls Series

An Invitation from the Publisher

Home Bird

3 September–December 1939

Heat burned May’s cheeks and stung her eyes so fiercely that water trickled from their corners. She jerked away from the searing blast, and the wailing continued.

‘Everyone’s running to the shelters! Come on, May, we’ve got to go!’ her sister Peggy’s terrified voice came from the open kitchen door.

May slid the beef into the hot oven and slammed the door. She knew she should leave the dinner, turn off the oven and run, but though the siren’s howl was like a cold knife slicing her heart, it opened a deep vein of defiance in May. If she could only carry on with the weekly Sunday dinner ritual, she told herself, then nothing could harm her home or loved ones. The keening note, rising in intensity, held all the essence of fear, the seeds of panic and the promise of loss that her eighteen-year-old self strained to resist. Momentarily, strength and youth drained from her limbs. But she held tight to the oven door, drawing courage from its domestic familiarity.

‘I can’t go to the shelter. I’ve got to put the dinner on!’ May said, her face flushed with heat from the oven and irritation with the Germans. ‘Typical! They have to choose a Sunday dinner time to start dropping their bloody bombs!’

She spun back to the oven, checking the temperature, while her sister strained to look up at the sky from the kitchen window.

‘Where’s George? He’ll get caught in it, and Mum and Dad! May, what the bloody hell are you doing? Come on!’ Peggy pleaded, her face an odd mixture of panic and bewilderment.

Just at that moment, their brother burst in, his face flushed, eyes wide with excitement.

‘She won’t come to the shelter, Jack. Tell her,’ Peggy said.

‘May! Didn’t you hear on the wireless? We’re at war! Leave the soddin’ dinner and get to the shelter now!’ His voice sounded unusually tight in his throat.

She stood her ground, back to the oven, as if shielding the heart of her home. ‘No, I’m waiting here for Mum and Dad, and then we’re having dinner.’

‘The dinner’ll be no good to us if we’re all dead!’

When she didn’t move, he grabbed her arm. ‘Come on, do as you’re told!’

She twisted out of his grasp. ‘Do as I’m told? Who put you in charge? You’re not in the bloody army yet, Sergeant Major!’

She registered the shock on his face. Normally she indulged her brother’s every wish, as they all did, but her defiance towards the Germans seemed to have infected her normal peace-loving nature with a belligerence that matched Jack’s own.

‘Well, I will be soon,’ he said lamely.

Just then May heard a voice calling her name. She slipped past Jack and dashed up the passage to find Flo, their next-door neighbour, peering anxiously in through the open front door.

‘You all right in there, love? Did your dad finish your shelter? If not, we’ve got room for two littl’uns in ours.’

‘Thanks, Flo, he finished it yesterday.’

Flo retreated into her own house and May peered out at the street. Peggy had been right. The whole world was in motion. All their neighbours in Southwark Park Road without Anderson shelters were streaming out of their houses, hurrying to the nearest public shelter. Suddenly May felt herself grabbed from behind. Before she could resist, Jack twisted her round. Grasping both shoulders, he propelled her along the passage, through their house to the back door and out into the garden. Trampling freshly dug, soft earth, she stumbled forward as he forced her head low enough to enter the dim, curving interior of the Anderson shelter. Whether or not anyone had put him in charge, Jack was undoubtedly stronger than May. Peggy was already settled inside as Jack slammed the heavy door shut, confining them all to the dark, damp womb of corrugated iron. She gave Jack an ineffectual thump on the arm and took a deep breath of dank air. A sheen of sweat covered her face and she found her legs were trembling, mostly with anger at being manhandled by her brother. But as she squeezed herself on to a wooden bunk next to Peggy, she realized she’d forgotten all about the dinner.

‘Oh no, I’ve left the oven on!’ she said, getting up.

‘Leave it!’ Jack growled, pulling her back on to the bunk. ‘You’re not going nowhere.’

She knew he was only being protective, but she hated it when he turned bossy like this. She had a feeling he was going to love this war.

‘We could be in here for hours!’ He was stronger but she was swifter, and before he could stop her, she dashed back into the house. She wouldn’t let a good bit of beef burn to a crisp for anyone, not her brother and certainly not Herr bloody Hitler.

And after all that, the first air-raid warning of the war turned out to be a false alarm. No planes darkened the skies; no bombs fell. It had been like the flick of a whip, a sharp warning of what was to come. After half an hour, spent mostly trying to quieten Peggy’s fears about their parents’ and her husband George’s whereabouts, May was back in the kitchen, and soon the oven was piping hot, ready and waiting for the roast beef.

‘See! If I’d listened to you, it would have been dry as Old Harry by now!’ she said to Jack, who was looking over her shoulder, waiting to steal a roast potato. She pushed him out of the kitchen. ‘They’re not done yet. You’ll just have to wait. And don’t blame me, blame Hitler.’

When her mother and father finally walked through the door, accompanied by Peggy’s husband George, May was laying the table. One look at Mrs Lloyd’s white face told her the usual leisurely Sunday drink at the Blue Anchor had been anything but relaxing.

‘Oh, me poor kids, and I wasn’t here!’ Mrs Lloyd said, crushing May to her and looking round at her other children. ‘Are you all right? I can’t believe I’m up the pub, just when the war’s finally started!’

‘I can,’ her father said, and winked at May as he took off his jacket and cap.

Her mother gave him a sidelong look.

‘Well, if it was up to May, we could’ve all been blown to pieces, so long as you still got your Sunday dinner!’ said Peggy, who had rushed to George’s side and was now helping him off with his overcoat and hat.

‘I’ll give it to her, if she ran the railways they’d always be on time.’ Her father smiled at May. ‘Keep calm and carry on. They don’t have to tell our May that, do they, love?’ he said, giving her an appreciative peck on the cheek.

In that moment May was glad she’d resisted being bullied out of her weekly task of cooking the Sunday roast. She’d taken on the job because it seemed the least she could do for her hard-working mother. And though she might pretend otherwise, May secretly loved it when Jack crept in to steal a roast potato before they all sat down to eat: Mum and Dad, Peggy and George, her brother Jack. The white cloth on the kitchen table, the steam from the scullery, the smell of the meat sizzling in the roasting tin. It was a tradition, home. And she was proud that the small matter of a German bomb had not prevented her from dishing up the Sunday roast.

‘Well, next time, not so much of the brave Jack Lairy,’ her mother said sharply. ‘If we’re not here, you just get yourself straight in the shelter!’

‘Beef turned out lovely, though,’ May said, noticing her father’s small smile as she placed the joint carefully in the centre of the table.

*

Peggy linked her arm through George’s as they walked home from her mother’s house. ‘I was worried about you.’

‘Hold up, Peg, we’re not runnin’ a race, are we?’

Twelve years her senior, George Flint suffered from bouts of breathlessness. Today he was bad. She’d learned to hold herself back when walking with him, but sometimes she forgot.

‘Sorry, love.’ She slackened her pace.

‘Well, if we’d been having Sunday dinner in our own home like most people do, I wouldn’t have been traipsing up to Southwark Park Road during an air raid, would I?’

‘Mum loves having us. I thought you liked her spoiling you?’

In spite of the age difference and his dubious occupation, George had always been a favourite with her parents. Wide’oh, as he was more commonly known, was the local bookie and though this was his primary source of income, he was involved in other unspecified ‘businesses’, which meant he was never without a wad of cash in his pocket. Yet it wasn’t so much his money that her parents approved of as his unconcealed, extravagant adoration of Peggy. This was the first time George had baulked at her mother’s insistence on having them there for Sunday dinner. She counted three of George’s laboured breaths before he replied.

‘Gawd’s sake, Peg, you’re a twenty-four-year-old married woman. It’s time your mother understood that. Anyway, I don’t want no one spoiling me but my wife.’ He put a hand over hers and pulled her closer. ‘I think we should knock it on the head, going round there

every

Sunday.’

The suggestion was no doubt reasonable, but it filled Peggy with unease. The regular Sunday gathering was a comforting anchor not just to her family, but to the girl she’d been before she married. Perhaps it was because her nerves were still jangling from the fright of the raid, but she wasn’t as careful in her reply as she normally would have been.