Ha! (31 page)

Authors: Scott Weems

When I told my wife about this finding, she asked why I wasn't a genius by now. After all, I've seen hundreds of comedies in my life, so why hasn't that made me the smartest man in the world? It was a good question. My reply was that I'm not a genius, but imagine how stupid I'd be if I hadn't watched so many

Fawlty Towers

reruns. It was the best comeback I could come up with.

Insight isn't the only complex cognitive skill that benefits from humor. Another is “mental rotation,” the ability to rotate objects in our headsâa common task for assessing spatial ability. As it turns out, people who are presented with funny jokes are faster at turning and twisting abstract shapes in their minds, even when the jokes involve minimal visual imagery. Reading funny jokes also improves our scores on creativity tests, reflecting increased mental fluency, flexibility, and originality. One study even showed that watching videos of Robin Williams's stand-up helps us come up with unlikely solutions for word-association problems.

It's hard to say why watching comedy makes us smarter and more creative. Perhaps, by being exercise for the mind, humor provides a

much-needed warm-up. As I shared before, in my life I've run two marathons, and both times I was in fair shape. But that was a while ago, and a lot has changed since then. Now if I tried to run that far I'd probably collapse into a fetal ball. Exercise doesn't change us forever, and neither does humor. As a form of mental exercise, humor keeps our brains active. Our brains must be exercised regularly, and when they areâwell, we become capable of just about anything.

B

ECOMING

F

UNNY

In 1937 fewer than 1 percent of respondents admitted to having a below-average sense of humor. Forty-seven years later, a similar survey showed that 6 percent of people admitted to being sub-par in the funny department. So, the question isâare people getting funnier, or are our self-concepts becoming slightly less deluded?

A rudimentary understanding of statistics reveals that the first explanation can't be true, because by definition at least half of us must be below average. I like to call this the “Dane Cook Effect”: no matter how funny we think we are, we're probably being optimistic. It's easy to believe we're funny when our spouse or mother laughs at our jokes. But the truth is, being funny is hard. If it were easy, everybody would be a comedian, even Dane Cook. I don't mean to imply that Cook is an unfunny individual. I've seen him perform, and I enjoy his stand-up immensely. Cook has earned millions of dollars from movies and comedy specials, yet his success hasn't stopped him from being openly disliked within the comedic worldâmostly because he's a master storyteller, not a comedian. His performances are certainly entertaining, but they're based on anecdotes, not on humorâlike Lenny Bruce except without the edge. Perhaps this is why a tournament of “The Sixteen Worst Comedians” held in Boston, Cook's home town, rated him “the worst of all time.”

Rolling Stone

once made a list of things funnier than Cook that included prune Danishes. Comedy is hard.

Sadly, textbooks can't teach us how to be funny like they teach us calculus. It's simply too complicated for that (even compared to calculus). But there are a few things that aspiring comedians ought to know.

Fortunately for people with unfunny siblings, there appears to be little genetic influence over humor. So it doesn't matter who our relatives are, because everybody has an equal chance of being funny. Scientists know this by comparing identical and fraternal twins, as well as biological and adopted siblings. Intelligence has a heritability of 50 percent, meaning that half our smarts are determined by our parents. Height has a heritability of over 80 percent. By contrast, for humor that figure is probably less than 25 percent.

Much of what we know about the comic personality comes from a book by Seymour and Rhoda Fisher, psychologists at the State University of New York at Syracuse. The book is titled

Pretend the World Is Funny and Forever

, and over the course of 288 pages it explores the pathways taken by more than forty professional comedians, luminaries such as Woody Allen, Lucille Ball, and Bob Hope. Through interviews, observational study, and background research, the authors break down the personality characteristics of these successful comics, looking for patterns in the life experiences that made them funny.

The authors found that fewer than 15 percent of the comics thought they would be professional humorists when they started outâevidently, it's never too late to think about getting into comedy. Most received little support from their parents. Many had been class clowns. And each expressed his or her humorous perspective in a unique way. Some were lavish and highly expressive, like Jackie Gleason. Others were quiet and reserved, like Buster Keaton. Still others were social and spontaneous, like Milton Berle, or reclusive, like Groucho Marx. It seems there are almost as many ways to act up and be funny as there are comedians. But they all had one thing in common: a deep interest in sharing observations with others.

“The average comedian moves among his fellows like an anthropologist visiting a new culture,” write Fisher and Fisher. “He is a relativist. Nothing seems natural or âgiven.' He is constantly taking mental notes.”

The idea that comedy involves observation isn't new, though it's still important. Humorists question everything they see, never taking anything for granted. They tell jokes and humorous anecdotes because they feel compelled to share what they see. Fisher and Fisher saw this desire in their interviews and even during psychological assessments like the Rorschach inkblot test. That involves looking at inky, amorphous blobs and describing what they look like, and when comics looked at these blots, rather than provide simple interpretations they consistently turned them into stories. Frightening wolfmen weren't evil, just misunderstood. A pig-like face wasn't ugly, it was endearing. A blot that resembled the devil was interpreted by one comic as silly, even goofy.

These observations show how an active mind is a humorous mind, and that the more we keep our brains working, the more our humor benefits. Consider also this important factâmaintaining a humorous attitude, as measured by the ability to recognize humor when it presents itself, is strongly related to actually

being funny.

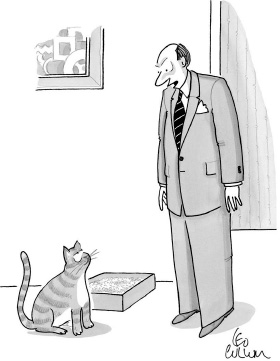

I'm referring to a study conducted by the psychologists Aaron Kozbelt and Kana Nishioka in which subjects were asked to identify the meaning and content of funny cartoonsâa measure of humor comprehension. Note that this is very different from appreciation. Appreciation was measured too, but here I'm talking about how well subjects understood the cartoons, a matter of recognizing the source of the jokes' incongruity. The researchers also measured humor production by asking subjects to come up with funny captions for an entirely different set of cartoons. Independent judges then rated how funny those captions were.

No significant relationship was found between humor appreciation and humor production, meaning that merely liking humorâas in, enjoying a good laughâdoesn't make us funnier. Rather, what matters is how well we understand the mechanisms behind the jokes. Consider

Figure 8.1

as an example.

“Never, ever, think outside the box.”

F

IGURE

8.1. A cartoon used to explore the link between humor comprehension and production. The ability to recognize that the man is warning against inappropriate feline creativity suggests an ability to actually

be funny.

Cartoon by Leo Cullum,

www.cartoonbank.com

.

If your interpretation is that the man is warning the cat against being “inappropriately creative,” then you understood the cartoon correctly. You are also more likely to produce funnier jokes, as found by the authors of the study. Specifically, those who score high on recognition also score high on production, even though subjective appreciation has no effect. In short, simply understanding jokes makes us funnier people.

If you thought that the humor stemmed from the man foolishly talking to a cat that doesn't understand English, you might want to buy a few joke books, or maybe get a subscription to

The New Yorker

and study a few more of its cartoons.

There's no shortage of companies willing to improve customers' sense of humor. For example, a workshop run by the comedian Stanley Lyndon promises that readers of his book will produce jokes 200 percent funnier than before. And an online course conducted by the ExpertRating training company offers to certify individuals in online humor writing, for a mere $130, as a way of preparing them for the lucrative career of comedy-club performance. From these programs, it might seem that learning to be funny is easy. It isn't. In fact, as discussed in this book's introduction, there's only one proven way to improve one's humor: namely, by following the

Rule of the Five P's:

practiceâand practiceâand practiceâand practiceâand practice.

I'm going to conclude this chapter with one last study, this time by the Israeli psychologist Ofra Nevo. She wanted to know what makes people funny, but rather than giving personality tests or administering surveys, she put groups of teachers through a seven-week course on improving humorâtwenty hours of training in all. Specifically, her aim was to find out if simply learning more about humor was enough to make people funnier to be around.

First, Nevo grouped her one hundred training subjects into several different experimental conditions. Some received an extensive humor training program, with numerous exercises providing background into the cognitive and emotional aspects of humor. They practiced telling jokes in front of larger groups. They talked about different humor theories and styles. They even explored its physiological and intellectual benefitsâmuch as we've done in this book. Others received similar training but without the practiceâa passive version of the humor training program. Still others received no training at all. All of the subjects took a humor assessment test at the beginning and end of the experiment, and received a questionnaire asking how helpful they thought the training was.

Nevo found that, on average, the subjects didn't find the training very helpful. They rated the program effectiveness between “small” and “medium”âthe equivalent of between 2 and 3 on a 5-point scale. She was disappointed by this result, but, as we'll soon see, perhaps she shouldn't have been. After the training was over, peers were asked to rate the subjects on their humor production and appreciation, with questions like “How much is this person able to appreciate and enjoy humor produced by others?” and “How much is this person able to create humor and make others laugh?”

As it turns out, the subjects who took the training scored significantly better on both measures, improving by up to 15 percent. Even those who hadn't practiced the techniques showed some progress. In short, although the subjects themselves thought they hadn't become any funnier, the people around them disagreed.

It's tempting to ask the obvious question: Only 15 percent? That hardly seems like much, especially compared to Stanley Lyndon's promise of 200 percent. But imagine how great it would be to be 15 percent smarter. Or 15 percent more attractive. If I were 15 percent taller, I'd be close to the size of an average center in the NBA. I'll take 15 percent any day.

Sadly, not much follow-up research has been conducted on Nevo's work, so we still don't know why the subjects in her experiment didn't “feel” funnier, even though their peers believed they were. One possible explanation is that sense of humor is a trait, as discussed earlier. Traits don't change quickly, meaning we'd need more than twenty hours of training to see obvious improvement. It might also be that changes in humorousness are subtle, more so than can be detected with scientific measurements. This might help explain why professional comics with years of experience often claim that they've only begun to learn their craft. Humor isn't something that can ever be mastered. It can only be learned.

And that learning occurs over a lifetime of practiceâand practiceâand practiceâand practiceâand practice.

Â

It is more enjoyable to read a humorous book than to read one explaining humor.

âA

VNER

Z

IV

“I'

VE GOT A SPOT

. I'

M GOING ONSTAGE NEXT

S

UNDAY

.”

That's what I told my wife Laura after finishing this book. I had signed up to perform a short act for amateur night at a local comedy club, and although I was terrified, it seemed the right thing to do. I had spent over a year of my life reading article after article, book after book on the topic of humor. My mind would never be more tuned to understanding, analyzing, and dissecting what makes jokes funny. If there was a time to apply that knowledge, this was it.