Hand of God (31 page)

Authors: Philip Kerr

‘You’ve got it all wrong. Nataliya didn’t use these for knocking out clients. That’s not how this business works. Not at our sort of level, anyway. No, these pills were for her. They’re antidepressants. A girl on Omonia Square might have done what you’re suggesting but not someone like Nataliya. At a thousand euros for a two-hour GFE she wasn’t exactly a hooker off the street.’

I showed her the next picture. ‘And I suppose the ceftriaxone was just in case she caught a cold.’

‘Accidents happen. It’s best to be prepared.’ She frowned. ‘How do you know all this anyway? About the Rohypnol? I thought you said the cops hadn’t found anything.’

‘They didn’t find it. I did. With the help of my driver, Charlie. He used to be a cop with the Hellenic police. We persuaded her landlord in Piraeus to let us into her flat and then had a nose around. I took her bag away for safekeeping. And I photographed the contents, as you can see.’

I handed her my phone and let Svetlana look at the pictures I’d taken.

‘For the moment I still have the bag although our team’s lawyer in Athens reckons that I will have to hand it over to the police sooner than later.’

Svetlana paused when she saw the picture of Nataliya’s iPhone.

‘So, the cops are going to want to speak to me after all. I mean they’ll almost certainly find my number on her phone. Not to mention a few texts, perhaps.’

‘Not necessarily. One of my players used to knock off phones for a living. He’s trying to break the code. It might be that I can erase one or two things before I hand it over.’

‘I see.’ Svetlana swept the screen of my phone to view the next picture and then frowned. ‘Wait a minute,’ she said.

‘What?’

She turned my phone around to show me a picture of one of Nataliya’s four EpiPens.

‘These EpiPens. I don’t think she was allergic to anything. In fact, I’m sure of it. I cooked for her. She’d have mentioned something like that.’

‘Charlie says that’s not why she had the stuff. He says Viagra is in short supply in Greece and that a shot of adrenalin will help some guys get it up.’

‘Nonsense. Believe me, there’s no Viagra quite as powerful as a twenty-five-year-old girl like Nataliya.’

She pinched the screen of my iPhone and enlarged the picture of the EpiPen.

‘Besides, look at the writing on the side of the box. It’s in Russian. This wasn’t even hers. This EpiPen was prescribed in St Petersburg.

To Bekim Develi

.’

‘What?’

‘She must have taken it.

Them

.’

For a moment I considered the possibility that Bekim had been using epinephrine as a performance enhancer, like ephedrine, for which Paddy Kenny had been busted while playing for Sheffield United back in 2009. Suddenly the heart attack started to look like it might have been self-inflicted.

‘Christ, the idiot,’ I muttered. ‘Bekim must have been using the stuff as a stimulant.’

‘Well, he was but not like you think,’ said Svetlana. ‘Bekim might have been a lot of things but he wasn’t a cheat. But surely you must know he suffered from a severe allergy?’

‘An allergy? To what?’

‘To chickpeas. He never travelled without at least one of these pens.’

‘Are you sure?’

‘Of course I’m sure. He told me himself.’

‘I’ve seen the medical report that was carried out prior to his transfer. There was no mention of any allergies.’

‘Then he must have lied to your doctor. Or the doctor agreed to cover it up.’

‘Our guy would never have done something like that.’ I shook my head. ‘But chickpeas. Surely that’s not very serious.’

‘Not in London, perhaps. But it is serious in Greece. They use chickpeas to make hummus. And for curries, of course.’

‘Christ. That explains the spaghetti hoops.’

Svetlana nodded. ‘As long as I knew Bekim he was always careful about what he ate. Especially in Greece.’

‘Then no wonder he didn’t let Zoi cook for him.’

‘If he’d accidentally ingested chickpeas, he’d have suffered anaphylaxis.’

‘And without the EpiPen that would have been potentially fatal.’

She nodded.

‘But surely someone at Dynamo St Petersburg, his previous club, would have known about this?’ I wasn’t asking her, I was asking myself.

‘And if they didn’t mention it?’ She left that one hanging for a few seconds before saying what was already in my mind. ‘That would have affected the transfer fee, wouldn’t it?’

‘It would have affected the whole transfer,’ I said.

‘I know Russians much better than I know football,’ said Svetlana. ‘They certainly wouldn’t allow the small matter of medical disclosure to affect a big payday. Not just his previous club, but Bekim, too. He was really delighted to go and play for a big London club. Russians love London.’

‘So they must have colluded in the deception,’ I said. ‘Him and Dynamo.’

‘Why not?’ said Svetlana. ‘Your own doctor probably just asked him a simple question. Are you allergic to anything? And all he had to do was answer was a simple “no”.’

I took a long hit on the cigarette and then put it out; the flavour brought back strong memories of prison when a single fag can taste as good as a slap-up meal in a good restaurant. I said: ‘The more important question now is what Bekim’s EpiPens were doing in Nataliya’s handbag?’

Svetlana didn’t answer. She lit another cigarette. We both did. There was much to think about and all of it unpleasant.

‘This is serious, isn’t it?’ she said after a while.

‘I’m afraid so. If Nataliya took his pens it must have been because she was paid to do it.’

‘By who?’

‘I don’t know. But forty-eight hours ago this guy from the Sports Betting Intelligence Unit – part of the Gambling Commission back in England – asked me if Bekim could have been nobbled. In spite of what I told him, it’s beginning to look as though he might have been.’

‘Nobbled? What does it mean?’

‘It means fixed. Interfered with. Doped, like a horse.

Poisoned

.’

I tried to remember the late lunch we’d all had at the hotel, prepared by our own chefs according to the guidelines laid down by Denis Abayev, the team nutritionist: grilled chicken with lots of green vegetables and sweet potato, followed by baked apple and Greek yoghurt. Nothing to worry about there. Not even for someone with an allergy to chickpeas. Unless someone had deliberately introduced some chickpeas into Bekim’s meal.

‘He must have eaten something with chickpeas in it before the match,’ I said. ‘There’s no other explanation.’

‘Okay, let’s work this out. How long before the match did you have lunch?

‘Three or four hours.’

‘Then that can’t have been it. When you have an allergy it’s almost instantaneous. He’d have gone into anaphylaxis the minute he ate the stuff. On planes they’ll sometimes tell you that they’re not serving nuts just in case a person who suffers from an allergy should inhale a tiny piece.’

‘Yes, you’re right. Which makes you realise that for someone who has got an allergy a nut or a chickpea can be as powerful as a dose of hemlock.’

‘And anyway,’ she asked, ‘why would someone do such a thing?’

‘Simple. Because on the night that Bekim died, someone in Russia took out a very big in-play bet on the match we played. These days, people will bet on anything that happens during a match: ten-minute events, the time of the first corner, the next goal scorer, the first player to come off – anything at all. It means that someone from Olympiacos, or someone from Russia, must have nobbled Bekim somehow. A ten-minute event like Bekim scoring and then being taken off. That must be it.’

‘Nobbled. Yes, I understand.’

I looked at my iPhone but as before there was no signal. ‘Shit,’ I muttered. ‘I really need to make some calls.’

‘You can’t,’ she said. ‘Not up here. But I could drive you into Naoussa where there’s a pretty good signal at the Hotel Aliprantis. I have a friend there who’ll let us use the internet, as well. If you think it’s necessary.’

‘I’m afraid I do. Svetlana, if I’m right, it wasn’t just Nataliya who was murdered, it was Bekim, too.’

Naoussa was a very typical little Greek town by the sea, with lots of winding, cobbled streets, low white buildings, and plenty of tourists, most of them English. The air was humid and thick with the smell of cooked lamb and wood smoke from many open kitchen-fires. Jaunty bouzouki music emptied out of small bars and restaurants and in spite of the English voices you would not have been surprised to have seen an unshaven Anthony Quinn step-dancing his way around the next corner. A line of Greek pennants connected one side of the little main square to the other and behind a couple of ancient olive trees was a taverna belonging to the Hotel Aliprantis.

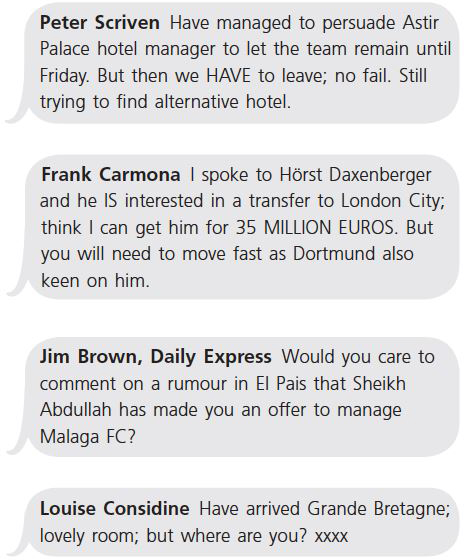

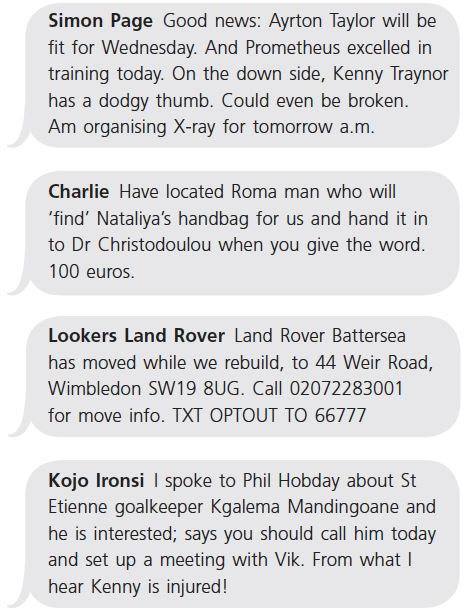

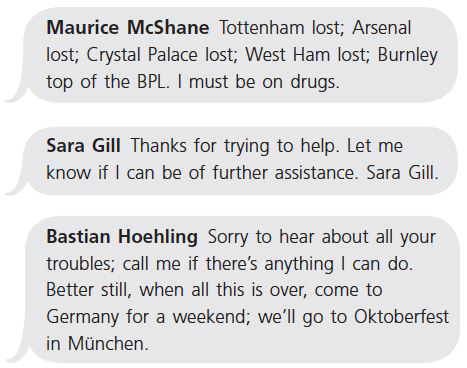

The minute we entered the place I got a five bar signal on my iPhone and the texts and emails started to arrive like the scores on a pinball machine; before long there was a little red 21 on my Messages app, a 6 on my Mail app but, mercifully, fewer voicemails. As Svetlana led me through the restaurant and into the little hotel’s tiny lobby I uttered a groan as life began to catch up with me again. But worse still, I’d been recognised by four yobs drinking beer and all looking as pink as an old map of the British Empire. It wasn’t long before the innocent holiday atmosphere of the Aliprantis was spoiled as they struck up with a typically English sporting refrain:

He’s red,

He’s dead,

He’s lying in a shed,

Develi, Develi.

and, just as offensive, although I’d heard half of this one before:

Scott, Scott, you rapist prick,

You should be locked up in the nick,

And we don’t give a fuck about Bekim Develi,

That red Russian cunt with HIV.

Svetlana spoke Greek to the hotel manager, a big swarthy man with a beard like a toilet brush, and then introduced me to him. We shook hands and as he led us both up to his office where I could make some calls in private and send some emails I was already apologising for what I could very clearly hear through the floorboards. Somehow, in the frustrating week I’d spent in Greece, I’d forgotten that when they wanted to be, a few English supporters could be every bit as unpleasant as the worst from Olympiacos or Panathinaikos. That’s football.

‘I’m sorry about that,’ I said.

‘No, sir, it is me who is sorry that you and your team should have had such poor hospitality while you are in Greece. Bekim Develi would often have a drink in here. And any friend of Bekim Develi’s is friend of mine.’

‘I ought to have realised I might be recognised. I should go. Before there’s any trouble.’

‘No, sir, I tell

them

to leave. You stay here, make your telephone calls, get your emails, I fix those bastards.’

‘All right,’ I said. ‘But on one condition. That I pay for their meal.’ I laid a hundred euro note on the desk in the office. ‘That way, when you tell them to leave, they’ll think they had a free meal and just clear off without any trouble.’

‘Is not necessary.’

‘Please,’ I said. ‘Take it from me. This really is the best way.’

‘Okay, boss. But I bring you something to drink, yes?’

‘Greek coffee,’ I said.

The manager glanced at Svetlana who asked for some ouzo.

I picked up the iPhone and started to read my texts.