Hat Trick! (9 page)

Authors: Brett Lee

The highest number of catches taken by a wicket keeper in a Test match happened in November 1995, when Jack Russell, playing for England against South Africa, took 11 catches. Bob Taylor (England) and Adam Gilchrist (Australia) have each taken 10 catches in a Test match.

Monday—morning

RAHUL

was fired up about doing the Madras Test for his cricket assignment and, amazingly, had arranged a couple of interviews, as we’d discussed. The teachers were impressed too. They said that it would ‘add another dimension to his assignment’, whatever that meant.

‘I guess that should give you all you need, Rahul,’ I said to him, hoping that he had lost interest in getting back to India. No such luck.

‘Toby, I have an opportunity to see cricket in my own country. You cannot possibly not take me back. Just once more, I say. Please?’

I shook my head. ‘I can’t. Jim said something about how tricky it is to take someone with you. How they can make it hard by getting too involved.’

But Rahul wouldn’t give up. After he had interviewed Dean Jones, he became even more insistent.

‘Toby, you wouldn’t believe how Dean Jones suffered. I talked to him on the phone.’

‘Yeah? What’d he say?’

‘That he lost seven kilos from the heat and humidity and that it took him two months to put it back on.’

‘Phew, must have been hot.’

‘Hot! It was over 40°C, with the humidity at 90 per cent. He couldn’t keep any fluid down, but he kept on batting and batting. All through the day. When he was on 170, he told Allan Border, who was batting with him, that he’d had enough. That he was really sick.’

Rahul paused, shaking his head.

‘And?’

‘Do you know what Border said to him?’

‘Course I don’t. What did he say?’

‘He said, “Okay, I’ll get someone tougher to come in.”’

‘But didn’t Dean Jones make over 200?’

‘That’s just it. He got the message. He stayed out there.’

Rahul was waving around a wad of notes he’d obviously scrawled during his phone conversation with Dean Jones.

‘I need to get my notes in order, Toby. I’ll tell you more tomorrow.’

Rahul caught up with me the next day, during lunchtime. He was out of control with excitement.

‘Toby, I’ve been thinking carefully about what you

said. And it’s true. When we went to Chennai I was just a bit overcome by the whole thing. But I know what to expect now. And I want to give you this.’ Rahul pulled a piece of paper out of his pocket and unfolded it. It was a list of points. ‘Go on, read it!’ he said excitedly.

- Toby is to decide when to do the travel, both to and from Chennai.

- I will not question his decisions.

- Toby is to carry this piece of paper with him while we are in Chennai.

- I will never ask to go again.

- I will tell Scott Craven everything I know about the time travel if I do not go once more.

Signed _______________ (Rahul) _______________ (Toby)

He looked at me expectantly.

‘You wouldn’t tell Scott Craven, Rahul?’ It was more a statement than a question, but it didn’t come out that way.

‘Yes, I would. I’m very sorry but I would. This is the opportunity of a lifetime for me. And for you, of course. You can’t go to India on your own.’

‘Why can’t I?’

‘Well, for one, you would get lost. You would need someone to help you with the language. With dealing with all the weird situations that can arise in a place like India.’

‘Maybe I don’t want to go to India.’

‘You know what? Dean Jones made 210 for the Aussies. He was throwing up on the field. He was totally exhausted. He was cramping. But he kept on going and going and going. When they finally got him out, he was taken to hospital. Or so they say. But was he? Or is it just a big myth? We can be the first to find out. As soon as I see Dean Jones lying in a hospital bed, then we can come straight home.’

‘But didn’t you ask him?’

Rahul looked up.

‘He has very little memory of what happened after he was out.’

‘Anyway, you didn’t write that bit about coming straight home on your little piece of paper here,’ I said, waving it in his face.

He grabbed the paper from me, pulled a pen from his shirt pocket, and squeezed in another sentence.

As soon as I have seen Dean Jones in hospital, we can leave.

‘No.’ As soon as I said it I knew I didn’t really mean it. I think Rahul did too.

‘What did you say?’ he asked, flabbergasted.

‘Oh, well, okay,’ I said, shaking my head. I thought for a moment that he was about to hug me. Instead he stuck out his hand. I took it.

‘You won’t regret this. I promise.’

We decided that I would stay the night at Rahul’s

on Sunday. Dad would drive me over to his place late in the afternoon. We would say that we wanted to put in a good couple of hours on our cricket projects as Mr Pasquali would be checking on our progress on Monday morning. We felt sure there wouldn’t be a problem.

‘You’re lucky, Rahul. I found some old

Wisden

s in Dad’s garage last weekend. I’m pretty sure he had the 1988 one.’

‘Fantastic. You won’t forget it, will you?’

‘I’ll try not to.’

Monday—afternoon

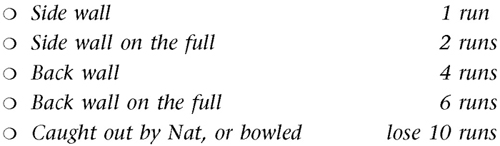

Nat had set the hallway up for a monster game of indoor cricket. She had bundled together 25 pairs of socks, all different shapes, sizes and colours. The game was simple, but heaps of fun. She would throw the socks at me as hard as she could. The wicket was an open door behind me. I had to belt the socks with the bat. The scoring was simple.

Having 25 pairs of socks was great—25 deliveries. It meant she had raided all available drawers in the house and that I was a good chance to make my 50—

as long as Mum didn’t catch us first. If I got my 50 I would definitely be giving Nat a bat.

‘Nat, you want a hit?’ I asked her. I’d made 67, but had been bowled once and caught once. I was happy with 47.

‘Only if you bowl under-arm.’

‘No probs.’ We gathered up the socks and I thought of Ally, the catcher in softball, as I pinged the socks at Nat, who was swinging the bat like a softballer.

After dinner I put through a call to Ivo at the hospital. He sounded pretty flat.

‘How are you feeling, Ivo?’

‘I’ve been better. But Mum says I’m over the worst.’

‘So will you be in there long?’

‘Probably another couple of days. I’ve got some internal bleeding, which they want to monitor or something. They had to operate too.’

I didn’t want to ask about the actual crash. I was assuming that no one else was hurt.

‘Watch out for driveways, Toby.’ Ivo’s voice was quiet.

‘You were on your bike?’

‘Yup. Remember that day in the gym when I had that headache?’

I nodded.

‘I was riding home and could hardly see, my headache was so bad, then this car rammed into me.’

‘Geez. They probably weren’t even looking.’

‘I think we both weren’t.’ There was a pause.

‘The cricket’s going well. We’ve got a one-dayer coming up this weekend.’

‘Oh, cool. They’re the best, aren’t they? When you can go home with a result. Hang on.’ I heard Ivo talking to someone. ‘I’d better go, Toby. Thanks for ringing.’

I liked Ivo. And I felt sorry for him, stuck in a hospital bed. Still, it sounded as if it wouldn’t be too long before he was back with us playing cricket. I wondered if Ally would be willing to give up her wicket keeping to him.

I rang the hospital again and this time asked for Jim, but he wasn’t available to talk.

‘Is he okay?’ I asked.

‘Who’s calling?’ said a bossy voice.

‘His grandson,’ I lied.

‘Well, you ask your mum or dad to ring.’

Maybe it was time to try a new one. A new fib, that is.

Wednesday—afternoon

We had our library session on Wednesday. Rahul told us all, including Mr Pasquali, more about his interviews. The one with Dean Jones had been by phone. Even Scott Craven was listening, though he pretended to be working. Gavin Bourke was so interested that he started asking a question—before Scott gave him a not-so-gentle whack in the ribs.

‘Go on, Gavin. That sounded like a good question,’ said Mr Pasquali, giving Scott a bit of a warning look.

‘Well, he said that you’d actually have to be there to get a feel for the heat.’ Rahul was looking at me, pointedly. ‘He said it was just shocking. And smelly too. There must have been some sort of sewerage place, nearby.’ Everyone was saying ‘yuk’ and ‘gross’ and wrinkling their noses.

‘It was gross!’ I said, without thinking. ‘I mean, it would have been,’ I stammered. ‘Rahul was telling me about it earlier.’ I felt my face going red.

I had brought Dad’s copy of the 1988

Wisden

to school. At the end of the library session I ducked over to the photocopier and copied the page describing the tied Test match. The scorecard for the game was on the second page.

I didn’t know what to expect when the sheets came out, but I was relieved to find that I could read them without a problem. The writing and numbers were clear and still. It must be the

Wisden

book itself that was the trigger for the time travel.

I folded the pages and put them in my pocket. I would practise with those, training my eyes to go straight to the correct spot. Hadn’t Jim said that, with practice, you could go to any specific part of a game by looking at the relevant section of the scorecard?

Rahul’s interview with Mr Bright, as he called him, was great too.

‘Poor Ray Bright,’ said Rahul. ‘You know, he was very, very sick too, just like Dean Jones. He almost didn’t play. He was so relieved when Australia won the toss and batted. It meant he didn’t have to go out into the field.’

‘So he just watched from the comfort of the dressing room?’ I asked.

‘Comfort? Oh, no. He lay on a table all day with wet towels on him. He doesn’t remember anything about that first day until the captain, Allan Border, came up to him with about half an hour to go and said, “You’re night watchy.”’

‘Night what?’ someone asked. Everyone was leaning forwards, listening to Rahul.

‘Night watchy. Night watchman. You come out if a wicket falls close to the end of play to protect the batters up the order.’

‘Sounds stupid to me,’ said Scott.

Rahul looked at him. ‘Well that’s what they did. And sure enough, a wicket fell and poor Ray Bright had to struggle off his sick bed—having eaten nothing all day—and walk out into 40°C heat to face the Indian bowlers.’

There was a pause.

‘Well?’ I asked.

‘It will all be revealed in my talk,’ Rahul said, smiling.

‘Yeah, but what happened to Bright?’ Gavin asked.

‘You’ll hear it all when I present my assignment,’ said Rahul with a cheeky grin. There were a few

groans of disappointment. ‘It’ll be just as if I was really there,’ he added.

I gave him a look. He just shrugged and smiled.

In a 1903 game between Victoria and Queensland, Victoria used only two bowlers in each innings. In the first, Saunders 6/57 and Collins 4/55 took all the Queensland wickets. In the second, two different bowlers grabbed all 10 wickets (Armstrong 4/13 and Laver 6/17).

Thursday—morning

BEFORE

school started the next day, Jimbo approached me when I was talking to Ally, Jay and Georgie.

‘Hey, Jimbo,’ I said.

‘Toby, can I ask you something?’

I moved away from the others and Jimbo followed.

‘I’ve been thinking a bit about our chat the other day. I want to find out some more about what happened the day my father decided to walk away from cricket, and I thought you might be able to help me.’

‘Oh,’ I was a bit shocked. Jimbo was the sort of guy who never asked for anything. ‘How could I do that?’ I asked.

‘All I know is that it happened on his birthday, which is the same day as the Boxing Day Test match. And I’ve also been hearing some pretty amazing things about some

Wisden

books and your ability to time travel from a library.’

‘You have?’ I asked, surprised.

‘Yes, from Rahul, and he isn’t the sort of guy to make up stuff like that.’

‘Rahul told you?’ I was stunned.

‘Not as such. But like I said, I’ve heard things. You know how you do.’

I wasn’t exactly sure what he meant, but somehow, if there was anyone who would know what was going on without appearing to—or even seeming interested—it was probably Jimbo.

‘Anyway, I rang up my grandfather and found out that Dad’s game wasn’t far from the MCG itself. It was in a big park where there are heaps of ovals and grounds.’

‘Hmm. So we go back to the Test match, then try and get to the ground where your dad is playing. And then what?’ Two lines from the poem ran through my mind.

Don’t meddle, don’t talk, nor interfere

With the lives of people you venture near.

‘Nothing. I just want to see and understand for myself why my father has made this decision. Then maybe I can accept it and we can get on better.’

I thought of Rahul and his reaction to the Madras Test.

‘Jimbo, strange things happen when you travel through time. You sort of lose control. You might do

something stupid. If you interfere with the past it can change things and stuff up the present.’

Jimbo looked at me hard. ‘I can be trusted, Toby.’

Jimbo rang his mum during lunchtime. He’d said she was a safer bet for getting permission for him to come round to my place.

‘Yeah?’ I asked as he put the phone down.

He nodded.

‘Yeah. I think she was actually pretty pleased. Dad’s going to pick me up at nine o’clock. He’s working late. I think that helped. Should you ring up your parents?’

‘Nah, it’ll be fine. I’m always bringing home friends. They’re used to it.’

I introduced Jimbo to Mum and Nat after school when they collected me. Mum seemed pleased that I was bringing home a new friend. She celebrated by stopping off for ice-creams on the way home.

Nat had taken a fancy to Jimbo right from the outset, and I had to wait till she had given him the full tour of the house before we could get upstairs and onto the computer.

‘Can we do corridor cricket?’ Nat whispered to me at my bedroom door. ‘I’m gonna get every pair of socks in the house—you’ll see.’

‘Okay, Nat, but later, okay?’

We logged into the best site on cricket that I knew. I had it bookmarked and often went there myself to check up on various games, especially the ones that Dad spoke about.

Every game—Test match, World Cup, one-day international and any other official first-class game—was listed. Most of them had full scorecards and match reports and some of the later ones even had a commentary so you could read what happened, ball by ball.

‘Jimbo, what year did your grandpa say for that game with your dad?’

‘Not sure, but it was early ’80s and the Boxing Day Test was an Ashes one, which means—’

‘Yep. Australia–England,’ I said, excitedly. I scrolled down, searching for the December Tests played in Australia. I knew that 1982 was an Ashes series; since England only came out every four years, it would have to be that year.

‘Oh, my God, Jimbo.’

‘What?’

‘It’s the 1982 Boxing Test match. The one that Border and Thomson had their huge last-wicket partnership and nearly won the game for Australia. Better still, Dad’s got the

Wisden

down there in the garage.’

‘What do you mean?’

‘The

Wisden

. It’s what we need to get there. And the exact game is down there, in the 1984

Wisden

!’

We spent the next 10 minutes looking over the scorecard. I told Jimbo the story about the match that I still loved having Dad tell me.

I was just up to the final morning when Dad called us down for dinner.

‘No worries. I’ll get him to finish the story. He won’t mind.’

We raced downstairs and into the kitchen. Dad told the story during dinner. He went a bit overboard when he got to the part about everyone stopping what they were doing to listen and watch the game. This time he had parliament stopping and trains and buses coming to a complete standstill as the whole country tuned into those fateful last minutes.

After dinner—and a quick game of corridor cricket—we raced back upstairs.

‘Okay, here’s the plan. We’re going to head out to play some cricket in the nets. On the way we grab the street directory from the car—’

‘And the

Wisden

book from the garage?’ Jimbo added.

‘And the

Wisden

book from the garage. No! We’ll go to the garage. Let’s go from there.’

Jimbo nodded excitedly. In fact, it was the most excited I’d ever seen him.

‘You are so going to like this,’ I told him.

‘It’ll be the best nets session I’ve ever had!’

I gathered up some loose change from my desk and we headed out, saying we were going for a hit in the nets at the oval across the road.

‘You expecting that someone has left all the gear there for you, too?’ Dad asked as we headed out the front door.

But Jimbo was a quick thinker. ‘I left my kit down in your garage, Mr Jones, we’re going to take that.’

‘Fair enough. You want an extra bowler?’

We stood there shuffling our feet.

‘Then again, maybe I’ll clean up the kitchen first.’

‘Okay, Dad.’ I felt a bit bad. Dad loved a hit. I’d make it up to him. We’d have a massive hit over the weekend.

A few minutes later the two of us were standing in the garage. Jimbo was holding the street directory, and I was holding the

Wisden

.

‘Here Jimbo. You find the Boxing Day Test match. Check the contents page.’ I passed him the

Wisden

and took the directory from him. I found the MCG and looked around for some green patches—ovals where his dad might have played.

‘Did your grandfather have a name for these ovals, Jimbo?’

‘Not that I recall. He just said that there were stacks of ovals, for rugby and hockey and soccer. Footy, and of course, cricket. Oh, and they were next to a hospital. A hospital that had—probably still has—a helicopter service. You know, for emergencies.’

‘Yep, I know.’ Jimbo heard the excitement in my voice. ‘I know exactly, I think.’

I flicked to the next page.

‘Got it. I reckon we’ll just take this with us,’ I said to Jimbo, holding the open page to him.

‘Here we go, England in Australia and New Zealand. Page 879.’ Jimbo flicked through the book.

‘Toby, you can get to any of these games? And this is just one

Wisden

!’

‘Yep. I think so. As long as there’s a scorecard for me to look at.’

Jimbo was shaking his head.

‘This is just crazy.’ He was searching for the right page. ‘What Test match was it?’

‘The fourth.’

‘Here we go. Pages 898 and 899. This is it.’

‘Okay, let’s swap again.’ We passed the books back.

‘What happens to the

Wisden

? Does it come with us?’

‘No, it sort of just falls to the ground.’ For the first time, Jimbo began to look a bit nervous.

‘You okay?’

‘Yep—let’s do it.’

‘Here, grab my hand.’ Jimbo took it. We sat down on the floor of the garage, next to the open kit.

I looked at the page of the

Wisden

. I must have been getting better at it, because almost straight away the shifting swirl of names and numbers had settled. Soon I saw a Cook, then a Fowler.

‘Cook, Cook,’ I said, slowly and clearly.

‘Now, Jimbo,’ I whispered as the familiar sound of rushing air and pressure surged through me.

A second later we were standing outside the MCG. I’m not quite sure how we managed to be outside the ground, but it was a good place to be. I had focused hard on the names of the first few English players on the

Wisden

page, and as I sensed the movement, kept my eyes away from the numbers. Even then, we had no idea how long it would take to get to the ground and then how long before whatever happened to Jimbo’s father actually happened.

Jimbo looked totally stunned.

‘Don’t ask,’ I said. ‘Just trust me. It works. We’ve just got to blend in.’ I looked at him. He was wearing runners that looked three sizes too big, the laces were undone, his cap was on back to front and his shorts went down below his knees.

‘Blend in as best we can,’ I added, spinning my cap the correct way. Jimbo’s mouth hadn’t closed.

We must have been the only two people walking away from the game. It was a beautiful sunny day and hordes of people with cheerful faces and huge Eskies were streaming towards the ground. Tight T-shirts, tight shorts, small white towelling hats, moustaches and thongs were everywhere. I felt as if I was from another planet, especially as I was walking away from the start of a Boxing Day Test match.

I spotted a line of taxis dropping people off.

‘C’mon, Jimbo.’

‘Yep. Just don’t leave my sight, Toby. You hear?’

‘I won’t.’

It proved easier than we thought and we didn’t

need the directory. We climbed into the back seat of a taxi, gave the driver the name of the park and took off.

The cab driver’s radio was blaring out a song I’d heard on one of those radio stations that play ‘Golden Oldies’ music.

‘I know this song,’ I said to the driver.

‘“Eye of the Tiger”? Of course you do—it’s on the radio all the time.’ He smiled.

I reached into my pocket and pulled out some coins.

‘Seven dollars will do you,’ said the driver. I handed over the coins. The driver grunted.

‘Well you can keep your foreign coin. That’s no good to me.’ He tossed a two-dollar coin back.

I opened my mouth, then closed it again quickly. He passed me back a few more coins.

We jumped out of the taxi and headed across the grass towards the first of the cricket games being played.

‘Hope none of those coins you have were made in the 1990s,’ Jimbo whispered to me. I hadn’t thought of checking. But it was unlikely the taxi driver would check himself. Still, it was a mistake. To have a coin floating around for 10 years before it had actually been made was something Jim would not be impressed with.

Jimbo had recovered well during the car trip, pointing out a few landmarks on the way that hadn’t changed. I think he was trying to convince himself that he wasn’t actually 20 years back in time.

There were a number of games going on, but it didn’t take us long to find the correct game just by asking for Jimbo’s father’s team. I could sense that Jimbo

was getting nervous, what with the time travel and now the thought of seeing his father. He had been pretty calm during the travelling part, saying little. But now he was edgy.

‘Remember, don’t get involved,’ I warned him. ‘We’re just here to watch, from the outside.’

Jimbo licked his lips, and nodded. ‘Yep. I know.’

We sat down by a tree and watched the game. A few wickets fell but nothing much seemed to be happening.

‘I reckon that’s him coming in to bat now,’ Jimbo said, as we watched a guy wearing glasses stride out to the pitch.

The first ball was a lifter and Jimbo’s dad just managed to fend it off his chest. The fielders were urging on the fast bowler, who we hadn’t seen bowl before.

‘C’mon, Cravo, give it to him!’ a fieldsman yelled.

‘Oh, my God,’ I whispered. ‘It’s Scott Craven’s dad!’

I stared at the bowler. He was big and strong, mean and fast, just like his son was going to be.

‘Like father, like son,’ I whispered.

But Jimbo wasn’t listening. The next delivery reared up and struck Jimbo’s dad a glancing blow on the side of the head. The next ball thudded into his chest. Jimbo winced and jumped to his feet.

‘Hey!’ he shouted. ‘He’s a tail-ender.’

A few of the fielders turned to look. Scott’s dad, who was bowling, didn’t. I grabbed Jimbo by the arm and pulled him down.

‘Jimbo, no!’ I said to him. ‘You can’t interfere. Remember?’

The last ball of the over was another bouncer and it caught Jimbo’s dad right above the eye. Jimbo gasped as his dad crumpled to the ground. His bat fell from his hand and toppled against the stumps. There was a shout of ‘Howzat?’ from the bowler. The umpire nodded, then raised his finger.

‘Yeah!’ shouted Craven and he pumped his fists in the air just the way I’d seen Scott do it so many times before.

I looked at Jimbo. There were tears streaming down his face and his fists were clenched. He wasn’t moving, though, which must have taken a lot of self-control.

A few of the fielders had run in to help Jimbo’s dad. There was blood streaming down his face. For a moment I felt sick, not only because of the injury but because of the rule that allowed a bowler to intimidate a player in that way, and even get him out just because he had lost control of the bat after being smacked in the face.

It just didn’t seem fair and I could sort of understand Jimbo’s dad’s decision never to play again.