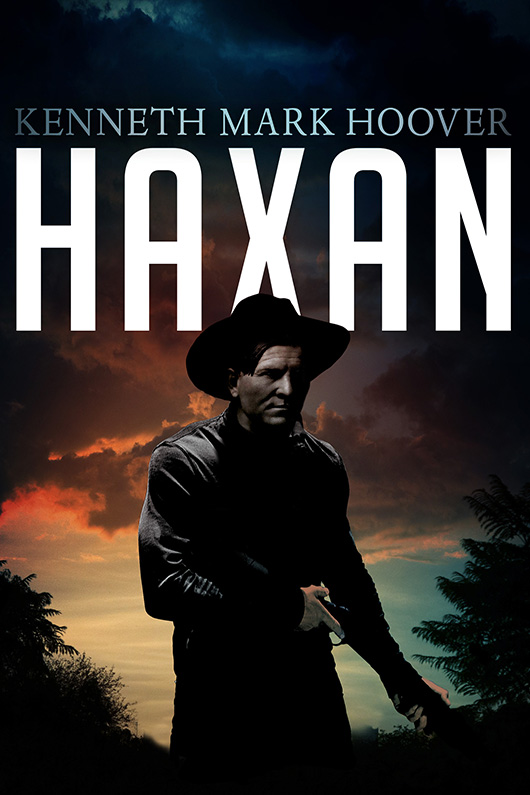

Haxan

Authors: Kenneth Mark Hoover

KENNETH MARK HOOVER

ChiZine Publications

for Gemma Files, who always believed

Thermopylae. Masada. Agincourt.

And now, Haxan, New Mexico.

We go where we’re sent.

We have names and we stand

against that which must be faced.

Through a sea of time and dust,

in places that might never be,

or can’t

become

until something is set right,

there are people destined to travel. Forever.

I am one.

—Marshal John T. Marwood

Haxan, New Mexico Territory

Spring, 1874

I

found the old man nailed to a hackberry tree five miles out of Haxan.

They had hammered railroad spikes through his wrists and ankles. There was dried blood on the wood and iron. Blood stippled his arms and chest. He was stripped naked so the westering sun could peel the flesh from his bones.

He was alive with I found him.

I got down off my horse, a blue roan I picked up in Mesilla, and went up to the man. His twitching features were covered with swarming bluebottles.

I swiped them away and pressed the mouth of a canteen to his parched lips. He was in such a bad way, I knew if he drank too much, too fast, he would founder and the shock would kill him.

He took a capful of water and coughed. Another half-swallow.

“I can work those nails out,” I said. “You might have a chance if a doctor sees you.”

He raised his grizzled head. His face was the colour of burned leather kicked out of a prairie fire. His eyelids were cut away, his eyes seared blind by the sun.

“Won’t do any good, mister.” He talked slow and with effort, measuring his remaining strength. He had a Scandinavian accent that could float a ship, pale eyebrows, and faded blue irises. “I been here two days.”

I tried to work one of the nails free. It was hammered deep and wouldn’t budge.

“No use,” he rasped. “Anyway, the croaker in Haxan is jugged on laudanum half the time. And the tooth-puller, he ain’t much better in the way of a man.”

I let him have more water. “Who did this?”

“People of Haxan.”

I tried to give him more water but he shook it off. He was dying and he knew it. He didn’t want to prolong the process.

“Why?”

“They’re scared. Like children are scared of the dark.”

He was delirious and not making sense. “Scared of what?”

“Me. What I know about this place.” His words and his mind grew distant together. “The ghost voices frozen in the rocks and the grass, the water and the sky. The memory of the world carried high on the wind.”

His head dropped onto his naked chest. He was losing strength fast. I tried to give him water again but he wouldn’t take it.

“What’s your name, mister?” he asked in a hoarse whisper.

“John Marwood.” I had other names, but he wouldn’t be able to pronounce them. Sometimes I couldn’t remember them all.

“I waited for you, son,” he said. “I called . . . but you didn’t get here fast enough. This moment . . . in time.”

I felt showered with ice.

“So you help her instead, Marwood. My daughter, I mean.”

“Let me help you first, old man. My horse can carry us both.”

“Thank you for the water. At least you tried.” His head rolled back. His breath sawed in his throat. “Did I tell you it snowed the day she was born?”

He gave a long, trembling sigh. With a sudden jerk his body slumped forward.

He was dead.

I cut him down and buried him in the shade of the hackberry tree. The sky was purpling in the east when I placed the last stone on top of his grave.

An hour of daylight remained. Across the empty landscape a single mourning dove flew to water. I walked over the hard ground looking for tracks. Two single-rider horses, well shod, and a wagon, had come from the north and gone back that way.

Headed for town.

The stirrup leather creaked when I mounted up. It was the only sound in the desert and it carried like a scream.

I shook the reins in my hand and pulled toward Haxan.

I

rode across a stone bridge that spanned a dry wash, remembering the old man. He was at rest now, but it took someone with a lot of hard bark on him to do something like that to another human being.

I knew what that was like. Carrying so much hate around inside until it blew you apart with dry, quiet winds.

I knew exactly what that was like.

The town of Haxan was a tumbled mix of old low-lying Spanish-style adobe buildings and brand new structures of ripsawed lumber going up around them like sawteeth. Some of the buildings were so new you could smell the resin seeping from the boards.

Haxan had all the earmarks of a boomtown. There were more saloons than schools, more dance halls than general stores. For those who couldn’t find lodging in town, a dirty tent city and clapboard shacks sprawled on the flat beside a foul-smelling creek.

It was the same story all over the

frontera

. Down in Texas, because of the war, cattle ran four dollars a head. They could be sold north for twenty along the Goodnight-Loving Trail. That brought money, but it also brought gamblers, drifters, thieves, and a bevy of soiled doves.

Enough to keep any lawman busy for a lifetime. However long that lasted.

There was a railway depot in Haxan for shipping beef, with a jumbled maze of cattle pens, corrals, and warehouses on the north side of town. A long street served as the main thoroughfare. It was bordered by weathered saloons, gaudy hotels, and painted store fronts. The outer facing of a mercantile emporium was covered in stamped metal panels, ordered from a mail catalogue. Beside it, two men rolled water barrels down a dirt ramp for storage in an underground cellar below a fancy French restaurant.

There were many waist-high stone walls throughout town, quarried from the San Andres Mountains that towered to the southwest. A roadrunner raced back and forth along one wall, seeking small lizards in the sun.

The livery stable stood on the other side of a wide-open plaza where a central public water well was surrounded by crude mesquite benches. Mexican women drew water for a cook pot. Their children bounced and chased a red ball.

In one corner of the plaza were several cottonwood trees, leaves rustling in the dry, desert wind. There were drifts of white gypsum sand, like snow, piled against the base of buildings and wooden sidewalks.

As I rode through town I noticed there weren’t many people around. It was much too hot despite the late hour of the day and they were in siesta. The only road traffic I saw were two ox-drawn

carretas

wobbling and screeching down Front Street.

The wire I received in Helena said the main freight office was in La Posta, a formidable adobe structure built by titled Spanish for the king’s rest. Those days of high royalty were long over, however. Now it was used as a mail drop for overland stages.

The mayor’s office was next door to La Posta. I drew rein and stepped out of leather. After tying my horse to the rail I pushed my way through the heavy wooden door.

It was cooler inside. The old adobe house had been converted to a way station and general office with walls a yard thick. The office had dark-stained furniture, chairs stuffed with horsehair, and a cochineal rug dyed from kermes bugs. Hand-hewn vigas supported a low ceiling that brushed the crown of my hat.

A blue-eyed man with balding red hair, and a nose with a bulbous tip, looked up from his paperwork. His shirtsleeves were rolled to the elbows. His hands were split by hard work and fishhooks, and his face wasn’t much kinder.

“Help you, stranger?” he asked.

“Looking for Mayor Polgar. I’m John Marwood. The War Department in Washington, D.C. sent me.”

He rounded his desk. We shook. “Glad to meet you, Mr. Marwood. Or should I say, U.S. Marshal?”

“John will do me fine.”

A smile split his seamed face. “Then you can call me Frank.” He hooked a thumb over his shoulder. “I own the freight service next door.” He chuckled. “Along with what little mayoring the good people of Haxan allow.”

He showed me to a horsehide chair. “We figured you to arrive on the eleven o’clock stage days ago, John.”

He offered me a Havana. I declined. I had a habit of taking an old briar pipe after supper and I hadn’t eaten yet. Polgar struck a lucifer against a sandpaper block and lighted his Cuban cigar.

“Got here fast as I could,” I explained. “Took a train partway and staged down from Montana Territory. Most of it I had to saddle.”

I had covered a lot of country after I received the telegram from Judge Creighton concerning my new appointment. Once I hit St. Louis I had some overdue paperwork in the U.S. Marshal’s office shoved under my nose. Finally, after I reached Mesilla, I picked up my horse and rode toward Haxan.

That was when I found the dying man in the desert.

However, I was certain Polgar didn’t want to hear about my cross-country travails. He had a directness about him, cold and sharp like the hooks that had scarred his hands.

“I wanted to get a feel for the countryside,” I said, expecting that would satisfy him.

He nodded. “Good idea, seeing how you’ll be stationed here for some time.”

“I hope so.” Now that the preliminaries were out of the way I thought it was time to discuss the job. Despite his open bonhomie I felt it’d be better to keep this part of the conversation on official terms. “Mayor, the telegram I got in Montana Territory sounded pretty desperate.”

Polgar waved his cigar in an off-hand gesture. “I must admit we didn’t know where to turn. We even set up a Haxan Peace Commission to show Washington we were serious about maintaining law and order.”

I didn’t like the sound of that. I preferred to work alone without someone gawking over my shoulder. A lawman that has to straddle a fence doesn’t live long.

“It’s bad enough answering to Judge Creighton when he’s sober,” I replied. “I don’t know if I want a busy-body commission full of old women telling me how to do my job.”

Polgar’s chair squeaked when he leaned forward. “You misunderstand, Marshal. All the propertied men in town are part of this commission. Men like Pate Nichols who owns the Lazy X. Hell, I’m on the commission, too. They’re all good men.”

I shook my head slow. I thought I had settled this with Judge Creighton when I accepted the badge. He knew when I took a job I preferred it my way or not at all. Now I had to make Polgar understand that as well.

“That’s even worse, Mayor. Propertied men sometimes feel they have a special provenance when it comes to the law.”

Polgar slapped his knee. “That’s not what we want, Marshal. We wired Washington and mailed a blizzard of letters requesting federal intervention in Sangre County. We wanted someone with a reputation.” He was a good politician. He liked to hear himself talk.

I decided to give up some ground. “All right, so long as we understand one another.” I was under no illusions this problem would not crop up again. I didn’t mind oversight, of course. That was expected. But men who pull political strings to get a certain lawman in their town often think they own him body and soul.

My soul had already been bought, and paid for, a long time ago.

Polgar looked relieved. Our first political skirmish had resulted in no serious bloodletting. He kicked back, legs crossed at the ankles. Like the rest of him, his boots were scuffed and marred. The man was a walking knot of flesh.

“So tell me, Marshal, how do you like our little corner of the world?” he asked. “I mean, from what you’ve seen.”

“Not much. I found a dead man south of town, nailed to a tree.”

Polgar’s sandy eyebrows came together. The silence between us lengthened like tempered chain. “Who was he?”

“He didn’t give a name. He was too busy dying.”

Polgar watched me with studied care. He laid his cigar aside. “The Navajo are peaceful and on reservation,” he said low. “Apaches, maybe. They get stirred up by the Army once in a blue moon.”

“I don’t think so.” I fished one of the iron spikes out of my grey duster and tossed it on Polgar’s desk. “Not unless the Apache have taken to pounding railroad spikes into people. It’s been my experience they are more civilized than that.”

Polgar picked up the railroad spike and rolled it thoughtfully between his thick fingers. He looked up, his blue eyes wary.

“What are you trying to say, Marshal?”

“Just this, Mayor. I’ve been in Haxan ten minutes and I already have one murder to solve.”

Polgar showed me the Marshal’s office located down the street. It was thirty yards west of the stone bridge I had crossed coming into town. It had a good view of the plaza and Front Street. The office was built of quarried stone faced with adobe mud mixed with too much straw. There were iron bars in the windows and thick wooden shutters with gun ports. Inside, the rectangular space was furnished with a desk topped with outdated wanted circulars and telegram blanks, a pine bench under a flyblown window, an iron potbellied stove, a rusted coffee pot, and a yellow map of Sangre County tacked to the wall.

The rifle racks were empty, but the jail cells in back were well oiled and the keys fit the locks. There was a rope cot with a cornshuck mattress for the jailer and a storeroom with enough room for one man to stand. A back door led to a broken hitch rail and a privy in a weed-choked lot.

“It’s not much,” Polgar apologized. “But long as you keep your appointment with the War Department your room and board will be paid at the Haxan Hotel, guaranteed by our commission.”

“Sounds fair enough,” I admitted. The office was a dark, lonely place. I had seen worse.

“You hungry, Marshal? Hew Clay owns the best hotel in town. He serves a good beefsteak.”

“Not now.” I put my Sharps rifle in the gun rack. It looked lonely there.

Polgar struck a match and fired a second cigar. He had a habit of smoking one halfway before tossing it aside and patting his pockets down with his rough hands for a fresh one. I figured a man hard up for tobacco would have a fine time just following him around town.

“John,” we were back on first name terms, “the only person who fits your description is old Shiner Larsen. He rode express guard for my outfit from time to time.” He was pointed with his next statement. “He built this town, don’t let anyone say different. Well, founded it, anyway. Same as.”

“What else you know about him?”

Polgar shrugged. “Not much. Kept a shack on the edge of town. Loner.”

“Larsen mentioned a daughter. What do you know about her?”

Instead of answering my question Polgar rapped a hard knuckle against the map. “Sangre County. Wild and dangerous, all four thousand square miles.” He paused. “You know what Sangre means in Spanish, don’t you?”

“I do.” Sometimes the very name of a place was strong enough to draw us in.

“John, this county is aptly named. This is a very bloody place. The man you’re replacing, Sheriff Cawley, set up a deadline on Potato Road. But after he quit all the saloons moved back into town.”

I sat behind the desk in a swivel chair that needed oiling and started hunting through the drawers. “Now they’re making so much money they don’t want to move back across the line,” I suggested.

“Exactly.” Polgar hooked his thumbs through his belt. His silver watch chain glinted from a broken shaft of light streaming through the window. “Out here a man must not only fight other men, but Nature herself. Sometimes, during the rainy season, Broken Bow River overflows its banks.”

I found a corked bottle in the bottom drawer. There was an inch and a half of good red eye in the bottom and a couple of dusty glasses. I didn’t like having liquor in the office, but there was no sense in having it go to waste, either. I set the bottle on my desk and poured at Polgar’s insistence.

“Broken Bow?”

“That’s what we call this bend of the Rio Grande. Thanks.” He accepted the shot of whiskey and we drank. Another splash for each of us finished the bottle.

Polgar motioned to the county map with his empty glass. “We’re digging

acequias

to handle overflow. But when the river floods it brings malaria, yellow fever, and property damage. Although with this current drought we’d be glad for a flood about now.”

If there is one thing that makes a lawman perk up his ears it is a mention of water rights. I remembered the men storing water barrels under the restaurant. “How bad a drought?”

“Cattlemen are complaining the coyotes are killing stock.” Polgar leaned his broad frame against my desk. “John, we need someone like you out here. A lawman with a tough reputation. I realize your jurisdiction is federal, but the Haxan Peace Commission wants to cede you local and county authority as well.”

I stoppered the empty bottle. “Sounds more like a double-edged sword than a help.”

“It will be,” he agreed. “Especially since you are the only U.S. Marshal in the territory.”

“I thought Breggmann rode out of Santa Fe.” He was a competent man. He shot two nightriders outside the Governor’s Palace a year ago after they got the drop on him.

“Guess you didn’t hear,” Polgar said. “Marshal Breggmann took after

comancheros

and trailed them to Palo Duro Canyon.”