Heart of Coal (25 page)

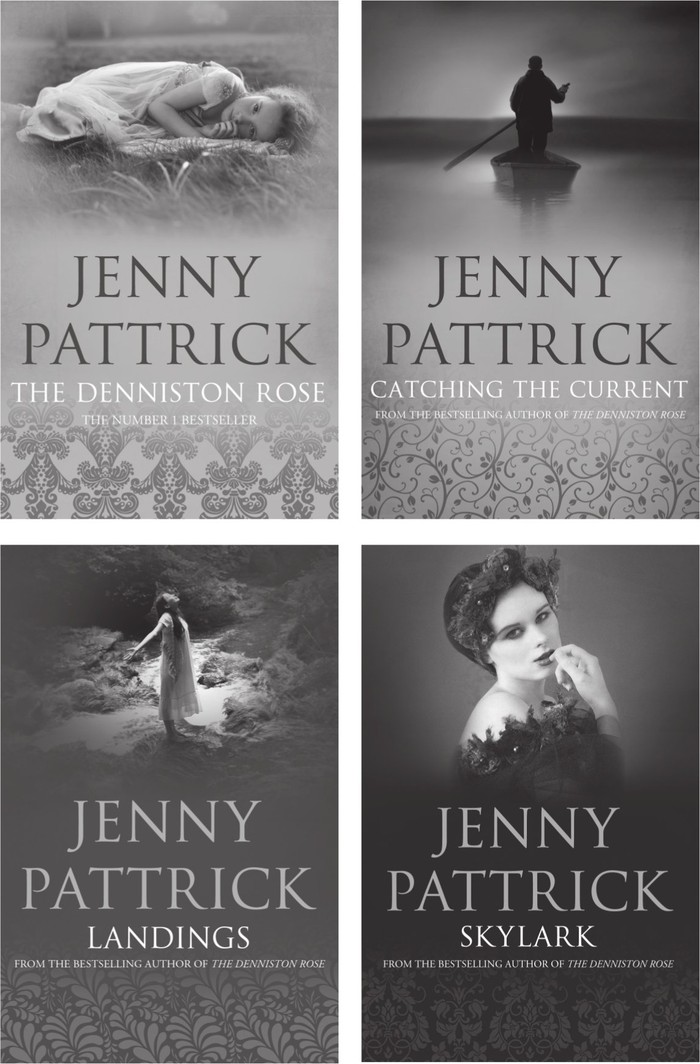

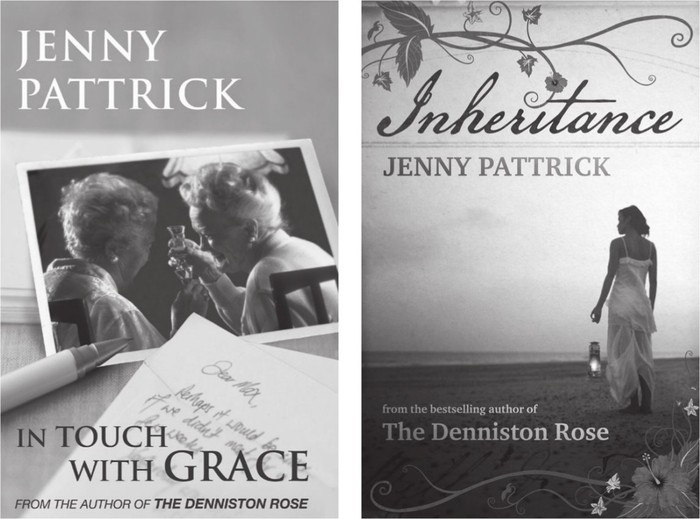

Authors: Jenny Pattrick

MARY SCOBIE LISTENS stony-faced to Brennan’s almost incoherent explanation. No, she says, it is simply not possible to change their plans. The trap is ordered, food at home will spoil if there are delays, she will in no way countenance travelling up to Burnett’s Face for the night. Brennan, she makes it clear, has a solemn duty to return her and the children to sea level this very evening. Brennan tries again. Only for one night. Rose has a right to see her children. Mary Scobie counters with her firmly held view that a mother who abandons her children has no future rights to them; and furthermore Brennan owes her an explanation over his failure to inform her about who the godparents were to be.

‘A child named after my own husband,’ she says, grasping her purse over her stomach as if to protect herself from further damage. ‘It was a slight not to ask me to godparent the boy. I was prepared

to overlook the matter. But then to choose that dangerous and thoughtless woman! I should have been warned.

You

should have warned me, son.’

Brennan, trembling, stands his ground. He wants to see Rose again himself, he says, and has made up his mind. This shocks and dismays his mother so much that for a moment she lacks a response. A tear springs to this battler’s eye, a sight that so unnerves Brennan that he almost gives in. His son Conrad is the one to save the day.

‘I want to see Mama too,’ he says. ‘Are we going now?’

Brennan takes a breath. ‘We are, son.’ And to his mother, ‘Janet will take care of you.’

Now, still shaking from the confrontation, he walks down towards Rose’s new house. Con trots beside him, one small hand in his father’s big one. Alice sits on Brennan’s hip asleep, her little arm around his neck and her fingers locked onto his collar. It is a new and satisfying feeling for Brennan, holding his two children like this. The spring air is sharp and clean. Despite his anxiety he grins.

‘What, Papa?’ says Con. ‘What’s so funny?’

‘We’re going to meet your mama!’

Con looks at him doubtfully. ‘That’s not funny.’

‘No,’ says Bren, still grinning, ‘but it might be fun!’

HENRY Stringer is curious. Guests have straggled away from Finnegans’ now; the Burnett’s Face contingent are trekking, still laughing and joking, back up home across the plateau. But Henry, who has been party to Rose’s plans, intends to spy on the tea-party between her and Brennan. He takes a walk on the playing field, ostensibly to enjoy a pipe on this calm evening, and strolls towards the edge of the flat ground. From here he can look down on the little shelf where Rose is building her house. There it is, perched on the edge of the plateau. It will be substantial — three good-sized

rooms and a kitchen. It is set sideways to the view so that kitchen and front room can both look down to the coast and out to sea — Rose’s stubborn idea. Who else but Rose would build a kitchen facing the road, for goodness sake?

One section at the back of the house has been roofed, and canvas, nailed to the timber frame, makes a covered and private room. Rose has slept here this past week. Henry cannot see into this room, but never mind. There they all are, their shadows long in the setting sun. Little Con is trying to climb up the framework. Rose and Brennan sit on folding canvas chairs, either side of the little card table she has borrowed from Henry. The spindly legs of the card table cast ridiculously long shadows across the raw wooden floors. Rose and Brennan sit there, caged by the timber struts but open to the evening air. The baby seems to be asleep in something. A drawer, perhaps? Food is on the table, and a pot of tea.

Are they talking? Both face out to sea, each with a hand flat on the table — close, but not quite touching. They seem relaxed. This day the Incline is silent: no rattle and clatter from the Bins. Even so, no words are audible. But yes! They are talking. Henry sees Rose lift her arm to point at little Con, who now folds his arms and taps his toes in a good imitation of a hornpipe. Brennan beckons to the boy and turns to Rose. The lad comes to her, holding something in his hand to show her. Rose bends to see, then turns sharply to Brennan. Her arms fly wide in a gesture Henry has often seen: why? How? Slowly, as Brennan talks, she lowers her arms, rests a hand on the table again. Now Brennan turns towards her; his hand moves to illustrate a point. To Henry it looks as if they are playing a careful game of cards.

He hears Rose laugh, sees her toss back her head in delight. Brennan’s lower chuckle joins in. Gently, as if reaching through water, he moves his hand to cover hers. She lets it rest there.

‘They will survive,’ says Henry to the setting sun. ‘In some unique way that only Rose and Brennan could imagine, they will survive.’

The whole scene is gilded — family, food and bare timbers — a deeper and deeper rose-gold as the sun slowly drowns. Henry watches. Now colour drains from house and occupants; the couple become clean-edged silhouettes high above the distant sea. Henry reaches his own hand out as if to steady himself, but of course there is no one, nothing to hold on to. He has felt, for a moment, not the sun sinking, but the world turning.

18 AUGUST 1967

There was no fanfare, no public holiday, the night the Incline closed. A handful of truckers saw the last wagons down and a skeleton crew filled them at the now almost derelict Bins. Even the weather lacked a touch of drama: gloomy, brooding skies, the air raw and windless. Officially the Incline was to stop at midnight, but the manager said the last load would likely go down earlier. Already much of the coal was being transported by the new aerial rope-way, and then trucked down by road to Waimangaroa. No point being sentimental, said the manager, about the Incline, which had lacked proper maintenance for a good few months. High time the scrappers moved in.

At the top of the Incline, near the brakesman’s hut, the Denniston Rose is standing. She is dressed beautifully: a wine-red

suit of fine merino wool, the skirt unfashionably long but falling in elegant folds to ankles that are still surprisingly fine. A scarf of rich purple is tucked at the neck, though one end escapes the lapel to lie jauntily over her shoulder. She stoops only slightly for all her eighty-nine years, in fact stands taller than the journalist beside her. Grasping rather than leaning on her stick, she takes no notice of him, but stares along the rails towards the waiting loaded wagon. Some bright ornament is pinned, rather incongruously for such an old woman, into her mass of white hair. A short distance away a photographer is picking his way over rails and wire ropes. He stops to look back at the old lady, then moves to a better angle. He shouts something that is lost in the rumble as the wagon is released to start its descent.

The wagon rattles down, wire ropes groaning, the shock of that descending weight vibrating up through the soles of their feet. In silence they wait for the empty to arrive. Then the photographer moves again. He stops to frame the shot.

The old lady shivers.

‘Shall I get you a coat or something?’ says the journalist. ‘He may take a while.’

She laughs at him. ‘No, no, young man, to me this is not cold. It’s the ghosts.’

They say she has buried two husbands. He touches the sleeve of her jacket to show sympathy, but she moves away. The journalist calls after her. ‘I think our fellow would like you to stay here.’

She waves at him without turning around, but walks on. She moves carefully, watching her feet. The step is firm and purposeful. Across the yard the photographer raises his arms in frustration. The reporter shrugs back. The old lady disappears into the brakesman’s hut. In a moment she is out again, laughing at some shared joke. The brakesman shouts a few words after her and she nods back to him.

‘I wanted to shake Andrew’s hand,’ she says when she is back at the reporter’s side. ‘The last brakesman. My father was the first, you know.’

‘Was he, now?’

‘Not that I knew it at the time.’

‘That he worked the brake?’

She laughs at him again. ‘Dear me, no. Everyone knows the brakesman. I didn’t know he was my

father

. By the time I did, there was nothing to be done about it.’

The journalist wants to pursue this interesting remark but Rose ignores him to follow her own line of thought.

‘He moved on. I thought him so solid and dependable back then. Everyone did. But he was a wanderer by nature. He couldn’t help it.’ She turns to smile at him. ‘It doesn’t do to go against your nature. I am a stayer.’

Another full wagon is shunted along the rails and waits to be hooked up. The woman everyone calls the Denniston Rose looks back towards the Bins. She waves to someone working there.

‘Your photographer fellow had better hurry up,’ she says, ‘or we may miss the boat. Shall I stand here?’

She throws her head back, tries one pose and then another. She is enjoying herself. ‘Wait a minute.’ She reaches up to untie the bright scarf, then hands it to the journalist. ‘We don’t need this.’ Her old fingers feel for a pendant that is now exposed at her throat. It is a small black heart edged with gold. She holds it towards him.

‘Look at that, now. This miner’s heart, young man, is purely of this place — Denniston coal, Denniston gold. Will the camera pick it up?’

‘I expect so.’

‘Good. My first husband gave it to me. No, my second.’ She centres it carefully at her throat between the wine-red lapels. Taps it

gently with her forefinger as if beating in time to a tune she hears in her head. Then lets it lie. ‘Now, are we ready?’

She straightens her back like a soldier and stares away to the distant hills. The journalist keeps talking to her, to keep the lined old face alive.

‘Will you go down now?’

‘Down where?’ She looks around as if he is suggesting she ride the Incline.

‘Off the Hill?’

‘Whatever for?’ she says, frowning. ‘What a silly question! I live up here. Why would I go?’

He is embarrassed to suggest her age, the empty streets, the derelict homes, never mind her children and grandchildren below. ‘With so many others gone —’

‘All the more need for someone to stay! Just because the Incline is stopping doesn’t mean the end of the world, young man. The best of the coal is still underground, even if the fools in Wellington don’t seem to recognise the fact.’

The photographer gives them the thumbs up. The Denniston Rose walks away from the Incline and stops at the edge of a small drop. To one side of them is an enormous slagheap. The area below — a broad ledge — is covered in scrubby bush. Here and there a chimney, abandoned when its house was demolished, rises through the scrub. The old lady waves her stick.

‘I grew up down there. With my mother in a big log house. Can’t even make out where, now. They called it the Camp.’ She looks down for a while, a half smile on her face.

‘Are they good memories?’ asks the journalist, his pencil and notebook ready.

Rose looks at him, head on one side, as if weighing up what to say. The old eyes are a clear blue still, and shrewd. After a while she

shrugs. ‘Good, yes. Good enough, I suppose. You remember the best parts, of course.’

She flashes him a wide smile and he recognises a formidable charm. ‘How did you know about me?’

He laughs. ‘Everyone knows you. The Denniston Rose. You’re a legend. Everything you’ve done! My mother — you taught her before she moved down — she says if she’d lived a quarter of your life she’d be crowing about it.’

‘Oh yes?’ Rose says, and smiles again, touching just once the heart at her throat. ‘I tell you what. To be honest I don’t want to wait for the last load to go down. No point looking back. Drive me up to the pub and buy me a drink. We’ll think of something cheerful to celebrate.’

As the two pick their way across to the road, ringing bells signal the arrival, below, of the final wagon-load. Brake handles are wound for the last time; cold water rushes into the pistons and the great brake-drum, groaning, slows, slows, slows again, and stops. In the sudden silence the long keening sigh of escaping steam reaches across the yard to halt the old lady. She turns for a moment and raises her hand, casually, as if to a passing friend, then continues on.

Readers may be interested in the real dates and events surrounding the period of this novel, and of

The Denniston Rose

.

1879

October 24th declared a public holiday in Westport for the opening of the Denniston Incline.

1881

First women and children arrive on the Hill. Some will not go down again for twenty years.

The drive through Banbury mine to Burnett’s Face is completed. 50,531 tons of coal produced.

First school opens, run by Miss Mary Elliot, the mine manager’s daughter.

Thirty colliers recruited from England arrive, via the Incline, at Denniston.

1883

New school built.

1884

The Track — a bridle path up to the plateau — opens.

1884

December: First miners’ strike in New Zealand begins, led by John Lomas on Denniston.

1885

June: Company capitulates. Returning miners drive scab labour off the Hill.

1895

Denniston the largest coal producer in New Zealand: 215,770 tons annually from 257 men underground.

1900, 1901, 1905

Denniston Brass Band wins West Coast championships.

1992

Road to Denniston opens, allowing wheeled transport up. The opening coincides with the end of the Boer War.

1905

Surface rope-road from Burnett’s Face to the Bins completed.

1910

Hospital built at Denniston.

Peak coal production (348,335 tons, 446 men underground).

Population of Denniston: 900; Burnett’s Face: 600.

1928-48

Major shift off the Hill. Many houses relocate to Waimangaroa.

1948

Government nationalises the Westport Coal Company, paying £900,000 for the assets.

1950s

Arial haulage-way built to take coal down to Waimangaroa.

1967

Denniston Incline closes. All coal transported by the aerial rope-way, truck and rail.

A small amount of coal is still mined privately on the Denniston Plateau. Millions of tonnes of coal remain underground.

The old school buildings are now a museum, open to the public, celebrating Denniston’s history.