Heinrich Himmler : A Life (20 page)

Read Heinrich Himmler : A Life Online

Authors: Peter Longerich

The league, which was a strong supporter of the ideology of ‘blood and soil’, was also anti-Slav, anti-urban, and anti-Semitic. Thus, from the start there was a close ideological affinity with Nazism, and a large number of Artamanen were in fact members of the Nazi Party. In 1937, for example, Friedrich Schmidt, who was leader of the league from 1925 to 1927, became head of the Nazi Party’s Main Indoctrination Department. His successor, Hans Holfelder, who was leader of the league from 1927 onwards, was also closely associated with the NSDAP,

48

and from September 1927 onwards he was Himmler’s link with the Artam League.

49

The league’s principles matched Himmler’s earlier enthusiasm for settlement in the east. Its model of how to live—a simple way of life, hard work, avoidance of nicotine and alcohol, sexual abstinence, adherence to Teutonic traditions—corresponded with the maxims that he himself followed. From 1928 onwards he acted as the Gau leader for Bavaria, a post in which he was confirmed in January 1929, only three weeks after his appointment as Reichsführer-SS (RFSS). The office of the Bavarian Gau was based within the building housing the NSDAP headquarters. Thus, Himmler was easily able to deal with the matters arising to do with the league. In fact there was only a very small organization in Bavaria, with about twenty members in all.

50

There is no record of Himmler having

played a very active part in the league; he can be shown as having participated only twice in events at the national level.

51

In fact his main role was to act as the link between the Nazi leadership and Holfelder. His involvement was very much ‘at the behest of the party’, as he later recalled.

52

For example, he recommended party members to join the Artamanen

53

and instigated the exclusion of those party members who had broken their work contracts with the league.

54

At the end of the 1920s the league became the scene of major disputes. At the end of 1929 there was a disagreement between one group, who wanted to focus above all on ‘selection and settlement’ and advocated a

bündisch

way of life modelled on the organizations of the German youth movement, and another group, whose members were more closely linked to the NSDAP and favoured turning voluntary service on the land into a labour service organization; they also advocated subordinating the league to the Nazi Party. Himmler was definitely a member of the second group, as is clear from a series of statements that he made in his role as deputy Propaganda Chief. Thus, in 1928, commenting on romantic agrarian ideas, he wrote: ‘internal colonization, cultivating heathland, horticulture—these are all forms of aid for declining, self-satisfied nations. Advocating internal colonization to a nation as a way out of a crisis simply means encouraging its cowardice.’

55

‘Settlement policy’, he noted succinctly in 1930, ‘can only ever be pursued after one has achieved power, never beforehand.’

56

At a meeting of the Artamanen ‘parliament’ (

Reichsthing

) on 21 December 1929 the

bündisch

group passed a motion of no confidence in the league’s leadership, which was closely linked to the NSDAP; in response they were immediately thrown out of the organization. Moreover, Friedrich Schmidt, referred to above, imposed a further sanction: he read out a letter from Himmler announcing that the group who had been defeated should also consider themselves excluded from the Nazi Party. Himmler, who was not present at the meeting, had evidently prepared this statement beforehand in anticipation of the row.

57

After the split, those who had been excluded established a new association called ‘The Artamanen’ and the NSDAP appeared to lose interest in maintaining close links with the Artam League. With the Nazi Party’s establishment of an agrarian cadre, the ‘Agrarian Political Apparatus’ headed by R. Walther Darré, in 1930 Himmler gave up his involvement in agricultural matters and, apart from that, sought to integrate the league into the Nazi Party.

58

As the NSDAP’s agricultural expert, for a short time in 1929 Himmler was responsible for editing

Der Bundschuh

, a weekly with the subtitle ‘A Fighting Journal for the Awakening Peasantry’.

59

In the first issue, which appeared on 2 May 1929, Himmler explained to its readers why the paper’s title was taken from the peasant revolts of the sixteenth century: ‘Four hundred years ago, the Bundschuh flag was unfurled for the first time as the German peasants rebelled against personal servitude and the lack of national freedom, against oppression and exploitation, and rose up in support of a great and unified Reich and for the rights of the ordinary man. And so, once again, the Bundschuh is being unfurled at a time of crisis for German peasants.’ The paper contained a mixture of practical information for its peasant readership and political and ideological contributions. There was a particular column devoted to the topic of ‘Peasant and Jew’. In addition, it regularly published the announcements of the Artam League.

Looking at Himmler’s role as the NSDAP’s agrarian expert during these years, it is clear that, while on the one hand his views on agriculture were imbued with völkisch ideology, on the other, he did not allow himself to be carried away by agrarian notions that were romantically inspired. In his view, what was decisive for solving Germany’s agricultural problems was the question of power: so long as the Nazi Party was not in control of Germany there was no point in trying to provide Germany with a new agrarian structure through settlement. Thus, to begin with, all efforts in this direction must be integrated into the party’s propaganda.

In the late summer of 1927 Himmler made a fateful acquaintanceship: he met Margarete Boden, his future wife. The date 12 September was specially marked out in his pocket diary; perhaps this was the day on which he saw Margarete for the first time. If this assumption is correct, they met in the town of Sulzbach in Bavaria, where Himmler was staying during one of his numerous speechifying trips.

60

In view of what we know about Himmler’s ideal woman, we should not be surprised by Margarete’s occupation: she was a nurse. The couple at once began a lively correspondence.

61

Her

letters have survived;

his

may also have done but are not available to researchers.

62

In any event, Himmler soon opened a special file for Margarete’s letters; he always scrupulously noted the date and time of their receipt.

63

He provided her with papers and newspaper cuttings and accounts of his travels in the service of the movement.

64

She was concerned about the dangers and burdens involved: ‘So you managed to get out of Brunswick all right, despite the fact that there was a fight. It’s sad that it always has to come to this, and not only for those involved.’

65

And on the following day she wrote: ‘Oh no -do you really have to speak 20 times in these 20 meetings? It would be awful. And you’ve got to go on doing this till Christmas.’

66

She repeatedly asked him about his health.

67

In November the correspondence became more personal. After Himmler had hinted that he had been a bit disappointed by her last letter, Margarete replied: ‘Frankly, I thought you would be pleased at getting two letters in such a short space of time.’

68

So why was he disappointed? Margarete kept probing, but evidently Himmler did not want to pursue the matter.

69

It is already clear from these first letters that Margarete Boden was an embittered woman: ‘Your letters always refer to my “mistrust” and my wish to give it all up. You’re right. I have lost faith in humanity, above all in men’s honesty and sincerity in their relations with women. Believe me, that’s worse than if one were just mistrustful. I’m really afraid of believing in the truth of words.’

70

Nevertheless, she was prepared to take the acquaintanceship further. They agreed to meet in Berlin.

71

During this meeting, which occurred in December, Himmler appears to have abandoned his dogged commitment to remaining celibate. After his Berlin visit they addressed one another in the familiar ‘Du’ form. Now her letters were addressed to: ‘My dear, beloved’, ‘My dear silly fool’, or ‘Silly fool and beloved’.

72

When she finally asked how she should address him in her letters,

73

Himmler suggested for the sake of simplicity ‘Heini’, which is what he had been called as a young boy. ‘What shall we call the “bigger” boy now? Something else?’ she replied mischievously.

74

In this first phase of their relationship, still committed to his role as ‘a soldierly man’, Himmler portrayed himself as a ‘freebooter’ (

Landsknecht

), and told her (as is clear from her letter): ‘We freebooters should really remain solitary and ostracized.’

75

However, the ‘freebooter’ was quite ready to confess his weaknesses. Thus, he complained to her about his continuing ‘submissiveness’ to his parents. ‘Surely you don’t think your “submissiveness” is noticeable at home?’, she wrote back. ‘In the first place it’s not in your character to change, at least not in a way that would be obvious. Secondly, it wouldn’t be a nice thing to do. Give in sometimes, my silly fool, but only if you yourself think you should.’

76

He also did not deny his dislike of big cities, indeed his fear of the metropolis. She replied by making gentle fun of him: ‘You needn’t be frightened of big cities. I shall do my very best to protect you.’

77

She regularly asked him about his stomach problems, which he was to complain about during the coming months, and enquired anxiously about the results of his visits to the doctor: ‘Did you go and see Uncle Doctor?’

78

From her letters it appears that Himmler believed his stomach pains were psychosomatic and attributed them to his constant attempts to discipline and control himself—to be ‘good and decent’, as he put it. He remarked to her that he would like once in a while to be allowed ‘not to be good and decent’, as a kind of therapy.

79

Himmler also appears to have admitted to her the issues he had with his outward appearance, for his rather insignificant and weak chin did not accord with his soldierly image of himself. ‘Why have you got your hand in front of your face?’ she commented about a photo he had sent her. ‘Did you want to cover up your chin?’

80

She quickly began to have doubts about the emotional basis of this new relationship: did he feel her deep affection as a burden? Did he doubt whether her love for him was as strong as his love for her?

My love, which will last for ever, should never be a burden to you, that is to say, never become too ‘much’. But you are convinced that I haven’t reached the right degree of affection because I just could not help saying when asked what I feel in my heart of hearts. Whether that feeling is still there I leave to you to sense, to feel. You write, ‘Whatever happens I will always feel the same towards you and love you always’, and, in spite of what you go on to say, that’s severe [ . . . ]. I cannot possibly think that you really feel I might not love you as much as you love me.

81

When she confessed to fearing that her love might be a burden to him, he troubled her by asking if he perhaps wrote to her too often. Did that mean, she wrote back, that he did not

want

to write to her so often?

82

Margarete Boden was an independent woman, who was very competent in her chosen profession and who, in her work environment, as head of nursing at a small private clinic in which she was a partner, behaved in an assured manner: ‘On rereading your letter I have just noticed that you wrote “small”. You’ll have to make that up to me. Anyway, it’s not true and you wouldn’t say that if you saw me in my clinic . . . ’

83

Yet this professional confidence concealed a deep insecurity.

The approaching end-of-year festivities provoked gloomy thoughts in her. ‘I dread Christmas for it is a festival of peace and yet what an awful year it was. The autumn was lovely, though, and it gave me faith in human beings again. I can believe and trust once more [ . . . ] Now I have to go across to the festivities. If only they were over, for I so dislike being the “matron”.’

84

The day before New Year’s Eve she wrote: ‘Tomorrow is the dreadful day when everyone is having a party and I must be alone. It really is awful. You see what a terribly discontented creature I am, wanting everything to suit me.’

85

She began the New Year full of pessimism.

86

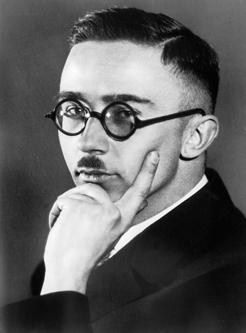

Ill. 4.

Heinrich Himmler in a photograph taken by Heinrich Hoffmann around 1930. Himmler covered his chin even for Hitler’s personal photographer.