Heinrich Himmler : A Life (26 page)

Read Heinrich Himmler : A Life Online

Authors: Peter Longerich

At the end of 1931 Himmler gave orders that the regional structure of the SS should be changed to conform to that of the SA. He subordinated the SS Abschnitte to two Gruppenkommandos (one for south, the other for north Germany) and appointed Weitzel and Dietrich as their chiefs.

68

In the course of 1932 they were joined by further Gruppenkommandos—East, South-East, and West—out of which the Oberabschnitte later emerged. Below this level there was a continuing increase in the number of Abschnitte. In January 1932 Himmler ordered the creation of SS Flying Units separate from the NS Flying Corps, in order to attract those interested in flying and gliding to the SS.

69

In April 1932, when the paramilitary units (SA and SS) were temporarily banned, the SS contained more than 25,000 members; after the ban had been lifted in June there were already more than 41,000.

70

This meant that the SS had succeeded in reaching the 10 per-cent quota fixed by Röhm, indeed in slightly exceeding it. The whole organization was financed half by membership contributions and half by contributions from so-called sponsor members.

71

In order to cope with these changes Himmler concentrated on consolidating the Munich headquarters. On 15 July 1932 he created an SS Administration Office (

SS Verwaltungsamt

) under a businessman, Gerhard Schneider. However, the ‘Reich Finance Administration’ under Paul Magnus Weickert was dissolved in October 1932. Weickert himself was dismissed from the SS, possibly on the grounds of embezzlement. This gave

Schneider the opportunity to expand the Administration Office, which was to fill a key position within the SS headquarters. However, in 1934 he too had to go because of embezzlement. The Weickert and Schneider cases were not the only errors of judgment that Himmler was to make in his appointment of key personnel.

72

In addition to such organizational measures, Himmler tried to unify the SS’s rapidly growing leadership corps in various other ways. For example, he arranged a special leadership course at the party’s so-called Reich Leadership School in Munich, to run from 31 January to 20 February 1932.

73

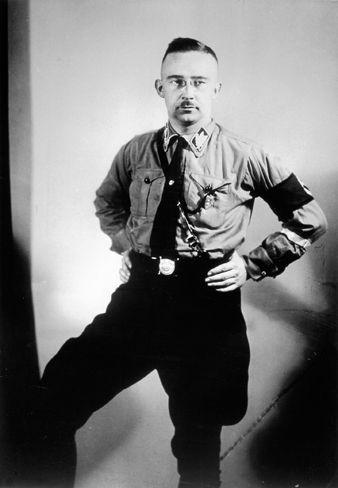

For the first time dressed in his black uniform, which after the course was introduced into the SS generally in order to distinguish it from the brown shirts of the SA,

74

he used this opportunity to give several lectures which, according to his later adjutant, Karl Wolff, covered ‘world revolution, the Jews, Freemasons, Christianity, and racial problems’.

75

In 1939, on the occasion of the tenth anniversary of Himmler’s appointment, Wolff described the impression his first meeting with Himmler made on him: ‘What impressed all those who had not yet met the Reichsführer-SS face to face was how, when marching slowly along the ranks, his clear eyes looked into our very souls. From this moment onwards he had succeeded in establishing the personal link that bound each one of us to his strong personality.’

76

During a post-war interrogation by the Munich prosecutor’s office, Wolff’s memory of Himmler’s appearance was rather different: ‘By contrast, Himmler’s appearance, pale and wearing a pince-nez, was rather disappointing. He lacked a strict military bearing and the self-confidence vis-à-vis an audience that one needs [. . .] If you talked to him one to one after his lectures his gleaming pince-nez no longer gave his eyes a distracting coldness and they could suddenly seem warm and even humorous.’

77

It may not appear surprising that the description of Himmler’s appearance that Wolff gave to the prosecutor differed from that in the piece celebrating his anniversary. Many of his contemporaries, however, noticed the different sides to Himmler’s personality revealed in Wolff’s descriptions—the coldness, the attempt to project authority, the insecurity which he endeavoured to disguise with informality and joviality. The contradiction between Himmler’s claim to be a member of an elite and his attempt to project a soldierly presence and the reality of his average appearance was only underlined by the smart black uniform which he had now adopted. Even the fact that Himmler had tried to give himself a suitable image, with a very short military haircut and a moustache, could not disguise the ‘pale, whey face, the receding chin and the blank expression’ that ‘Putzi’ Hanfstaengel, Hitler’s foreign-press chief, who for a time shared an office with Himmler, could remember so well.

78

Ill. 7.

Himmler gained in self-confidence with his success in building up the SS. But he tried to conceal his continuing awkwardness in relations with other people by adopting an ostentatiously ‘soldierly’ bearing.

During a six-hour train journey that he shared with Himmler, Albert Krebs, a Nazi functionary from Hamburg, gained the impression of a man who was strenuously trying, through his self-presentation, to compensate for what he felt he lacked. According to Krebs: ‘Himmler behaved coarsely and he showed off by adopting the manners of a freebooter and expressing anti-bourgeois views, although in doing so he was clearly only trying to disguise his innate insecurity and awkwardness.’ However, what Krebs found really intolerable was the ‘stupid and endless prattle that I had to listen to’. Never in his life had he heard ‘such political rubbish served up in such a concentrated form and that from a man who had been to university and who was professionally engaged in politics’. Himmler’s conversation had been ‘a peculiar mixture of warlike bombast, the saloon-bar views of a petty bourgeois, and the enthusiastic prophecies of a sectarian preacher’.

79

Evidently Himmler’s constant urge to express his views, for which he had continually criticized himself in his diaries, had not waned in the meantime. In fact the opposite was true, and, when combined with the self-confidence which he ostentatiously displayed, it clearly got on the nerves of those around him.

During the years 1929–32 a centrally directed and highly structured mass organization had been created from what had begun as a few dozen ‘protection squads’ (

Schutzstaffeln

), which were scattered across the whole of the Reich, consisting of no more than a few hundred men and functioning mainly as bodyguards for Nazi leaders. This success was not primarily due to Himmler himself, but above all to the fact that, as a newly appointed Reichsführer-SS, in 1929–30 he found himself in the middle of an historically unique process of political radicalization and mobilization, which worked in favour of the NSDAP. To begin with, his contribution lay essentially in creating organizational structures which made it possible to divert from the flood of hundreds of thousands of predominantly young men who wanted to join the SA a certain proportion into the SS, and at the same time to keep pace with this tremendous growth.

During these years Himmler demonstrated for the first time in his life real organizational talent. The strictly hierarchical structure into which he was integrated as Reichsführer-SS was evidently much more congenial to him

than the more opaque situation that had confronted him as secretary of the Lower Bavarian Gau or as deputy Propaganda Chief. In those positions he continually had to mediate between the different views held by party headquarters and the rank and file, a role which he clearly found difficult. Moreover, he had also developed an—albeit vague—idea of how the SS should develop, which went far beyond the protection of NSDAP leaders and the provision of an internal party intelligence service. He envisaged an elite guard, associated with the idea of racial selection, which would have the utopian future task of reviving the ‘Nordic race’. And he had recognized that, in order to strengthen its position within the Nazi movement, one thing was essential: absolute ‘loyalty’ to the party leadership, through which the SS could differentiate itself from the SA.

Despite repeated electoral successes, the NSDAP did not succeed in forming a government. According to the Weimar Constitution, the Reich President was by no means obliged to appoint the leader of the largest party as Chancellor. On the contrary, the Constitution permitted him to rule without parliament, thanks to his power to issue emergency decrees. If a parliamentary majority opposed government policy, he could dissolve the legislature.

In the spring of 1932 it became clear that the Brüning government, which had hitherto been supported by Reich President Hindeburg’s emergency decrees and by the SPD in parliament, was coming to an end. Of all things it turned out to be the ban on the SA and the SS, which Brüning had issued in April, that initiated the demise of his government. General Kurt von Schleicher, who had opposed the ban on ‘military-political’ grounds, spun a wide-ranging intrigue against the Chancellor, which eventually led to his fall.

80

Von Schleicher made an agreement with Hitler behind the scenes: Hitler offered to support a new presidential government if the NSDAP’s paramilitary organizations were once more allowed to operate freely and if new elections were held. In return, Schleicher did his best to undermine Brüning’s position with Hindenburg. Hindenburg finally dismissed Brüning on 30 May 1932, and appointed Franz von Papen, an old friend of Schleicher’s, as the new Reich Chancellor. Von Schleicher took on the post of Reich

Defence Minister. The Reichstag was dissolved in accordance with the agreement with Hitler, and new elections fixed for 31 July. The ban on the SA and SS was lifted punctually in mid-June to coincide with the start of the election campaign. On 20 July the Papen government replaced the Social Democrat-led government of Prussia with a ‘Reich Commissar’, and thereby removed one of the Weimar Republic’s last defensive bastions.

In these elections the NSDAP achieved its greatest triumph hitherto; it won 37.4 per cent of the vote. After this success—the party had once again managed to double its vote compared with the previous election of September 1930—the NSDAP assumed that it was about to seize power. In east Germany Nazi activists stepped up their campaign of violence to produce a wave of terror. They were in the process of breaking with the party’s ‘policy of legality’ and moving towards an open revolt against the state. On 1 August 1932, the day after the Reichstag election, the SA and SS launched a series of bomb attacks and assaults on the NSDAP’s opponents in Königsberg. A communist city councillor was murdered, and the publisher of the Social Democrat newspaper

Königsberger Volkszeitung

, as well as the right-wing liberal former district governor (

Regierungspräsident

) of Königsberg and another communist functionary, were seriously injured. In the coming days this campaign of terror was extended to the whole of East Prussia and then to the province of Silesia, with further attacks and murders.

81

There is clear evidence that it was Himmler who was primarily responsible for the Königsberg terror campaign and gave the orders to Waldemar Wappenhaus, the leader of the East Prussian Standarte. There is a letter in Wappenhaus’s SS personal file dated 1938, in which, commenting to the SS’s head of personnel on accusations that had been made against him, he referred to old ‘services’ he had rendered. After all, ‘in 1932, as leader of the Königsberg Standarte’, he had ‘carried out the RFSS’s order to finish off the communist chiefs’ and, as a result, had suffered ‘police persecution as a wanted man’.

82

Wappenhaus’s reference to the way in which orders were issued at the time is a rare document. Naturally, in the quasi-civil war situation of the years 1930–3 documents relating to political murders were not kept by the SS, and although after the takeover of power there was much talk of the ‘heroic deeds’ of the ‘time of struggle’, the unpleasant details of the terror campaigns of those days were concealed. In future Himmler too preferred to remain silent about his role in these violent political conflicts.

Violence meted out to political opponents, their ‘elimination’, was never a moral problem for Himmler. As we have seen, during his student days he had already played an active part in paramilitary organizations and come to terms with the idea of a civil war. He had been involved in an armed putsch. He regarded the post-war conflicts as merely an extension of the World War, for which he had prepared so thoroughly during his military service. As far as he was concerned, the Weimar Republic’s years of stability were simply a short interlude in the struggle against ‘Marxism’, which had to be destroyed.

In August 1932, by taking vigorous measures, the police and judiciary managed once again to put a stop to the wave of violence launched by Nazi supporters in eastern Germany. It was against the background of these conflicts that, on 13 August, the decisive meeting took place between the election victor and the Reich President, at which—and that was the firm conviction of the Nazis—Hindenburg would offer Hitler the office of Reich Chancellor. The Reich President, however, merely asked Hitler to cooperate with the new government and, after the latter declined to do so, published a statement in which he publicly repudiated Hitler.

83