Here Comes the Night (29 page)

Atlantic had opened the year by offering generous sales incentives to distributors—delayed billing, one in every seven records free—but the company had not rebounded. Wexler denied rumors to

Billboard

in November that the label was in talks for sale with Jerry Blaine and his Cosnat Distributing Corporation. While Cosnat was Atlantic’s largest single outlet and undoubtedly held considerable receivables over the cash-poor company, the Blaines were unlikely to be able to put together that big a deal. “Our only relationship with Cosnat is that they distribute for us in some areas,” Wexler told the trade magazine, “but I never mind taking Blaine’s money on the golf course.”

Wexler thought the entire market for singles had gone soft, by perhaps as much as 50 percent. His strategy was to double the number of Atlantic’s releases. “But these are not just any records,” Wexler told

Billboard

, “they have to be records the firm feels are potential hits. They must be worked on with great intensity throughout the country, so that each one gets a full shot at regional action that might bring it into national hit category.” He needed Berns.

Meanwhile, Berns was chafing increasingly under Mellin’s stingy adminstration. He had made tons of money for the poncy old bastard, and now Berns wanted a share of his publishing and he wanted his

own record label. He negotiated a new music publishing contract with Mellin while conspiring with Wexler to go to work for Atlantic. Mellin and Berns discussed terms during his trip to England. Mellin agreed to start a new publishing company, fifty-fifty with Berns. He gave Berns more money. They signed a new deal in November, about the same time Atlantic’s law firm was drawing up their contract with Berns.

Berns wanted his own label, and Atlantic and Berns agreed to start a record label that would be wholly owned by Berns and distributed by Atlantic, much like the deal with Stax. In addition, Atlantic also secured the services of Berns to produce artists already signed to Atlantic. They agreed to pay $300 a week advance on royalties.

The first single for Berns’s new label was already in the can—a rocking little romp called “Baby Let Me Take You Home” that somehow managed to catch the fresh excitement of the new rock and roll records that were starting to appear. Berns wrote the song with Wes Farrell, professional manager at Roosevelt Music and another one of the cast of characters at 1650 Broadway, who had only recently started writing with Berns.

In his new post as staff producer at Atlantic, in the weeks before Christmas, Berns would take over the most successful brand name vocal group in the history of rhythm and blues and begin producing the Drifters.

Johnny Moore had rejoined the Drifters in April. He first sang with the old Drifters in 1955, before the Five Crowns took over the name. During the group’s next recording session (where the group cut “Only in America,” among others), gritty vocalist Rudy Lewis had also recorded a couple of solo sides, as if Atlantic was gearing him for a solo career along the lines of Ben E. King. But Moore and Lewis got along, so the group expanded to five members with two capable lead vocalists (not including guitarist Billy Davis, a fixture in the group’s music for many years whose real name was Abdul Samad). During their final session with the group in August, Leiber and Stoller cut

another Bacharach and David song, “In the Land of Make-Believe,” which didn’t even chart.

In December, Berns took over the Drifters recordings in a three-song session at Atlantic Studios. The Drifters had outlasted entire epochs of changing styles since the group first appeared ten years before on yellow label Atlantic 78s. They were the flagship of the Atlantic fleet. Berns immediately abandoned the glistening percussion and celestial strings of the Leiber and Stoller productions in favor of a more hard-edged, spare sound with prominent, swinging horns. “Beautiful Music” was a half-hearted rewrite by Leiber and Stoller (with Mann and Weil) of their “(My Heart Said) The Bossa Nova.” “Vaya con Dios,” the old Les Paul and Mary Ford hit, featured female voices in the foreground of a Drifters record.

It was “One Way Love,” more than the others, however, that signaled the Berns era of the Drifters. Written by Berns and Ragovoy, the track glides along taut, clean lines, as lead vocalist Johnny Moore flies over the group vocal with the orchestra’s stop breaks punctuating the title lyric. The song takes a darker look at relations between the sexes than the typical Drifters romantic fantasy. Handing over the production duties for the Drifters to Berns was more than a symbolic gesture. Berns needed to reinvest this valuable property with new life.

If taking over stewardship of the Drifters wasn’t enough, within days of each other, he would also make his two most towering records yet with both Solomon Burke and Hoagy Lands.

Both sides of the Hoagy Lands record were epics; from the thumping twelve-string guitar introduction of “Baby Let Me Hold Your Hand” that could have been lifted from a Leadbelly record to the majestic finale of the other side, “Baby Come On Home,” Lands pleading over the gospel choir’s harmonies and Gary Chester’s cymbal crashes. Unlike the pared-down version of the song Berns and coauthor Wes Farrell recorded as the Mustangs, Berns takes Lands through a fully orchestrated landscape of “Baby Let Me Hold Your Hand,” booming

guitars, chorale harmonies, and a fierce, driving charge led by drummer Chester, a powerhouse track that never lets up. “Baby Come On Home,” a classic Bert Russell tune, moves grandly to a more elegant pace, Lands reciting the opening verse, leading to the wide-screen chorus, a curtain of voices draped behind him. The command, confidence, and personal vision Berns marshaled on this record was unequaled thus far in his career.

With Burke, he recorded one of the soul singer’s own compositions, another cover of a country and western standard (“He’ll Have to Go”) and another new Berns-Farrell composition, “Goodbye Baby (Baby Goodbye).” Over the sweetly cooing Cissy Houston choir, Burke gives the song everything. He moves easily from a warm, calm intimacy to powerful, cantorial heights on the chorus. He drops his voice at the end of the verse into his deepest, richest tones, as the chorus explodes behind him and everybody goes to church. Burke’s innate dignity lifts up a song that could easily be mired in its gloom.

You made me lonely

You made me hurt

Just like a fool, I gave you candy

And you fed me dirt

But I’m coming to your party

And just before the break of day

I’m going to kiss you one more time

Then I’m going away

Goodbye, baby

Baby goodbye

—

GOODBYE BABY (BABY GOODBYE), BERNS-FARRELL (1963)

With this new, upward juncture of his rocketing career, Berns was his own man. His rich, singular musical vision had been realized beyond anything he could have imagined as he was standing in the studio making “A Little Bit of Soap” a scant two years before. He arrived

at the utter heights of the music game in New York just in time. Within weeks, forces nobody could have predicted would sweep through the pop music world from all the way on the other side of the Atlantic Ocean.

*

Montgomery would later record for Motown Records under the name Tammi Terrell, where she was best known for duets with Marvin Gaye. She died from a brain tumor after collapsing onstage in Gaye’s arms.

J

OHN LENNON POPPED

a couple of Zubes throat candies in his mouth and lit a contraindicated Peter Stuyvesant cigarette. After more than twelve hours in EMI’s Abbey Road studios, the Beatles were one track short of finishing the group’s first album. Since it was past ten o’clock at night, the official triple session was over. The last three hours, the band had slammed down five songs from the group’s well-practiced stage act, finishing with a cover of Burt Bacharach’s Shirelles song, “Baby It’s You.”

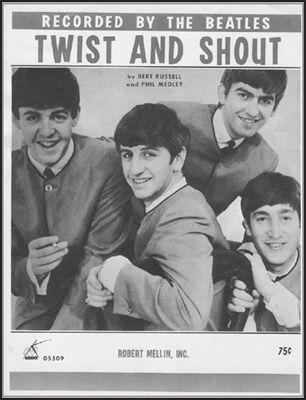

The four musicians and producer George Martin repaired to the cafeteria. While Lennon bathed his scorched throat in warm milk, the others drank tea. They wanted to try one last song, “Twist and Shout.” The band had been using the song to close its shows starting the year before. They had been playing the number, fresh off the U.S. charts by the Isley Brothers, since the band’s final nightclub engagement at Hamburg’s Star Club, whipping up hometown crowds with the song during their last shows at the Cavern. They had picked up the tune from another Liverpool group, Kingsize Taylor and the Dominoes, and had even nicked the guitar part in the middle from the Dominoes’ version.

Lennon took off his shirt and laid it across a bench. He gargled quickly with a mouthful of milk and counted off the take. He tore into the song—

Well, shake it up, bay-ay-bee

—pushing his ravaged voice

past the pain threshold. His throat would hurt for days. He staggered through the number, wrenching the vocal out of somewhere deep inside. His raw, inflamed flesh is there for all to hear, embedded in the performance. Paul McCartney’s triumphant

Hey!

punctuates the close. A perfunctory run at a second take was made, but Lennon spent it all on the first. The group’s manager, Brian Epstein, had to promise the tape operator a ride home to get him to stay for a playback. What they had committed to tape in that last half hour was nothing less than the most rugged, powerful piece of rock and roll that had ever been recorded in a British studio.

At the time the session was held in February 1963, “Please Please Me,” the group’s second single, was sitting on top of the British charts. The band had gone from down the bill on a tour starring Helen Shapiro, the British teenage pop vocalist best known for her 1961 hit, “Walking Back to Happiness,” to third-billed on a show headed by two American rock and roll acts, Chris Montez and Tommy Roe. “Twist and Shout” closed the band’s every show.

In July, on the heels of the Top Ten success of a cover of “Twist and Shout” by Brian Poole and the Tremeloes on Decca, a label still smarting from passing on signing the Beatles, EMI released a four-song EP by the Beatles titled

Twist and Shout

. The debut album,

Please Please Me

, had been released in March, hit number one on the charts in May, and stayed there for thirty consecutive weeks. No album since the

South Pacific

soundtrack topped the British charts from their inception in 1958 to 1960 had even remotely approached that kind of popularity. When the first $90,000 royalty check arrived for Berns’s “Twist and Shout” cowriter Phil Medley, his wife insisted they buy a house with the entire proceeds, convinced they would never see another check like that again. Berns went to England to see for himself.

“Twist and Shout” may have been an unlikely rallying cry for a new generation of British youth from an American perspective, but rock and roll meant something entirely different to people growing up

in postwar Britain. London still wore the scars of the Blitz. Bombed-out buildings stood on every block. A thin, charcoal blanket of coal dust, a hundred years old, covered the city. Few Londoners had central heat; most were warmed in the cold London winter by coin-operated gas heaters. London was still getting to its feet. War babies raised on rations were reaching their teens.

America looked like a shining New World, home of cowboys and Indians, gangsters and molls, enormous automobiles, Disneyland and all manner of exotic delights far beyond the gray realm of the British Isles. The country had watched one of the greatest empires in history crumble. Once the mightiest nation on earth, Britain had lost the lead to America in commerce, industry, communications, arts, world politics, culture, everything. English schoolkids marveled at Hollywood films such as

Rebel without a Cause

or

Blackboard Jungle

and wondered if life could really be like that in the United States.