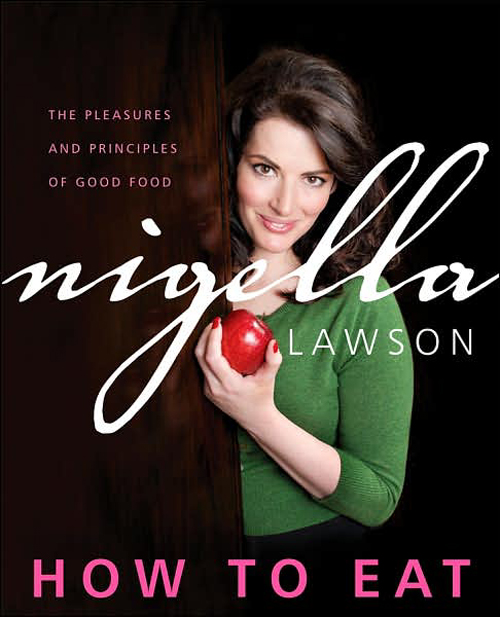

How to Eat

Authors: Nigella Lawson

N

IGELLA

L

AWSON

HOW TO EAT

T

HE

P

LEASURES

AND

P

RINCIPLES OF

G

OOD

F

OOD

In memory of my Mother, Vanessa (1936–1985)

my sister Thomasina (1961–1993)

and for John, Cosima, and Bruno

with love

Contents

Feeding Babies and Small Children

Cooking is not about just joining the dots, following one recipe slavishly and then moving on to the next. It’s about developing an understanding of food, a sense of assurance in the kitchen, about the simple desire to make yourself something to eat. And in cooking, as in writing, you must please yourself to please others. Strangely, it can take enormous confidence to trust your own palate, follow your own instincts. Without habit, which itself is just trial and error, this can be harder than following the most elaborate of recipes. But it’s what works, what’s important.

There is a reason why this book is called

How to Eat

rather than

How to Cook

. It’s a simple one: although it’s possible to love eating without being able to cook, I don’t believe you can ever really cook unless you love eating. Such love, of course, is not something that can be taught, but it can be conveyed—and maybe that’s the point. In writing this book, I wanted to make food and my slavering passion for it the starting point; indeed, for me it was the starting point. I have nothing to declare but my greed.

The French, who’ve lost something of their culinary confidence in recent years, remain solid on this front. Some years ago in France, in response to the gastronomic apathy and consequent lowering of standards nationally—what is known as

la crise

—Jack Lang, then Minister of Culture, initiated

la semaine du goût

. He set up a body expressly to go into schools and other institutions not to teach anyone how to cook, but how to eat. This group might take with it a perfect baguette, an exquisite cheese, some local speciality cooked

comme il faut

, some fruit and vegetables grown properly and picked when ripe, in the belief that if the pupils, if people generally, tasted what was good, what was right, they would respect these traditions; by eating good food, they would want to cook it. And so the cycle continues.

I suppose you could say that we have had our own unofficial version of this. Our gastronomic awakening—or however, and with whatever degree of irony, you want to describe it—has been, to a huge extent, restaurant-led. It is, you might argue, by tasting food that we have become interested in cooking it. I do not necessarily disparage the influence of the restaurant; I spent twelve years as a restaurant critic, after all. But restaurant food and home food are not the same thing. Or, more accurately, eating in restaurants is not the same thing as eating at home. Which is not to say, of course, that you can’t borrow from restaurant menus and adapt their chefs’ recipes—and I do. This leads me to the other reason this book is called

How to Eat

.

I am not a chef. I am not even a trained or professional cook. My qualification is as an eater. I cook what I want to eat—within limits. I have a job—another job, that is, as an ordinary working journalist—and two children, one of whom was born during the writing of this book. And during the book’s gestation, I would sometimes plan to cook some wonderful something or other, then work out a recipe, apply myself in anticipatory fantasy to it, write out the shopping list, plan the dinner—and then find that, when it came down to it, I just didn’t have the energy. Anything that was too hard, too fussy, filled me with dread and panic, or, even if attempted, didn’t work or was unreasonably demanding, has not found its way in here. And the recipes I do include have all been cooked in what television people call Real Time: menus have been made with all their component parts, together; that way, I know whether the oven settings correspond, whether you’ll have enough burner space, how to make the timings work, and how not to have a nervous breakdown about it. I wanted food that can be made and eaten in a real life, not in perfect, isolated laboratory conditions.

Much of this is touched upon throughout the book, but I want to make it clear, here and now, that you need to acquire your own individual sense of what food is about, rather than just a vast collection of recipes.

What I am not talking about, however, is strenuous originality. The innovative in cooking all too often turns out to be inedible. The great modernist dictum, Make It New, is not a helpful precept in the kitchen. “Too often,” wrote the great society hostess and arch food writer Ruth Lowinsky, as early as 1935, “the inexperienced think that if food is odd it must be a success. An indifferently roasted leg of mutton is not transformed by a sauce of hot raspberry jam, nor a plate of watery consommé improved by the addition of three glacé cherries.” With food, authenticity is not the same thing as originality; indeed, they are often at odds. So while much is my own here—insofar as anything can be—many of the recipes included are derived from other writers. From the outset I wanted this book to be, in part, an anthology of the food I love eating and a way of paying my respects to the food writers I’ve loved reading. Throughout I’ve wanted, on prin-ciple as well as to show my gratitude, to credit honestly wherever appropriate, but I certainly wish to signal my thanks here as well. And if, at any time, a recipe has found its way onto these pages without having its source properly documented, I assure you and the putative unnamed originator that this is due to ignorance rather than villainy.

But if I question the tyranny of the recipe, that isn’t to say I take a cavalier attitude. A recipe has to work. Even the great abstract painters have first to learn figure drawing. If many of my recipes seem to stretch out for a daunting number of pages, it is because brevity is no guarantee of simplicity. The easiest way to learn how to cook is by watching; bearing that in mind, I have tried more to talk you through a recipe than bark out instructions. As much as possible, I have wanted to make you feel that I’m there with you, in the kitchen, as you cook. The book that follows is the conversation we might be having.

OVEN TEMPERATURES

°F

description

275 very cool

300 cool

325 warm

350 moderate

375 fairly hot

400 fairly hot

425 hot

450 very hot

475 very hot

Approximate minutes per pound

ROASTING CHART

Beef

Starting temperatures, °F : 475

After 15 minutes, °F : 350

Rare: 15

Medium: 18

Well done: 25

Chicken

Starting temperatures, °F : 400

After 15 minutes, °F : 400

15+10 overall

Duck

Starting temperatures, °F : 425

After 15 minutes, °F : 350

20

Goose

Starting temperatures, °F : 400

After 15 minutes, °F : 400

15+30 overall

Lamb and venison

Starting temperatures, °F : 425

After 15 minutes, °F : 400

Rare: 12

Medium: 16

Well done: 20

Pork

Starting temperatures, °F : 400

After 15 minutes, °F : 350

30

Veal

Starting temperatures, °F : 425

After 15 minutes, °F : 350

20

There is more than one way to skin a cat; you may well find that, throughout this book, instructions are given for cooking various meats in the oven at temperatures or for times that differ from those given in the chart. There are many variables in roasting, as in cooking generally, but the chart, drawn up with my butcher, David Lidgate, should provide a clear and reliable guide to roasting times. An important factor in following these timings is the temperature of the meat before it goes into the oven. If it’s fridge-cold the guidelines are irrelevant, inadequate; all bets are off. Let the meat stand, out of the fridge, to get to room temperature before you cook it as instructed. After the meat has had its advised cooking time, test it; either press it (if it feels soft, it’s rare; bouncy, it’s medium; hard, it’s well done) or pierce with a knife to see. With chicken, stick a knife in between the thigh and the body; if the juices run clear, it’s cooked. And always let meat rest out of the oven for at least 10 minutes before carving.

FISH

Go to a fish seller, while they still exist, to get good advice and wise information and to ensure, please, their continuing existence. Going to a fish seller, like going to a butcher, makes life easier where it matters—in the kitchen. I go for good fish, good meat, no funny stuff. But once there, I make the most of it; butchers and fish sellers have skills that we don’t. Don’t feel apologetic about asking a fish seller to fillet or a butcher to bone. When I order fish or meat, I practically hold a conference to discuss every possibility, every eventuality; I pick brains, ask for advice on cooking, and relentlessly exploit the expertise on offer. So should you.

For those times you can’t get to a fish seller, I suggest you check the advice offered by the Canadian Department of Fisheries concerning cooking times: for every 1 inch of thickness, cook the fish, by whatever means—frying, grilling, poaching, baking—for 10 minutes; for a whole fish, measure at its thickest point and multiply accordingly. I heed this advice, but I alter it; I reckon that 8–9 minutes per inch will do, so I recommend changing the 1-inch rule to 1¼ inches, thus giving myself an extra quarter-inch for the Canadians’ 10 minutes. When baking fish, whether wrapped in buttered foil or not, I use a 375° F oven. Obviously, there are exceptions. (See pages

289–290

for notes on cooking a whole salmon.) And there are times when I ignore these rules altogether.