HETAERA: Daughter of the Gods

Read HETAERA: Daughter of the Gods Online

Authors: J.A. Coffey

Daughter of the Gods

J.A. COFFEY

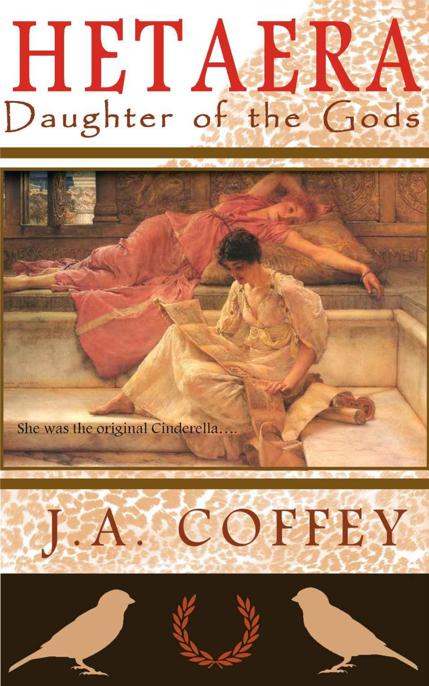

Cover image: “The Favourite Poet, 1888” Sir

Lawrence Alma-Tadema

Text copyright © 2013 Julie A. Coffey

All Rights Reserved

ISBN-13 978-1482785395

ISBN-10 1482785390

Please note:

A portion of the

proceeds from sales of this book are donated by the author to combat human

trafficking and modern-day slavery. To find out more, including how you can

help, please visit Polaris Project at

www.polarisproject.org

.

As is the way of

writers, we recognize that we stand on the shoulders of others to achieve our

dreams. This book would not have been possible without the following people:

To my mother, a

stalwart champion of all my endeavors. You are the model for following my

dreams.

To my sister, she

of the red-gold hair, whom I always admired and aspired to be. You are a

Thracian in my heart.

To the many authors

and editors who encouraged me to persevere in an industry which often doesn’t

support budding authors--the incomparable Jody Wallace (sorry it took me so

long to get it right!) and my critique partners of RWA; editor Mary Theresa

Hussey, for comparing me to one of my giants and thereby giving me hope; editor

Anna Genoese (for calling me out and making me want to be better); to authors

Mary Renault and Jacqueline Carey-women who showed me it was possible to write

the book of my heart; to Sarah for an eagle’s eye and a red pen (and whose work

I hope to one day read--you have been called!); and to Hope for friendship and

support.

To STM for the

mistakes and pain—both given and received.

But mostly to my

husband, Robert, for unfailing love and with whom the yoke of a marriage bed is

a most joyous and lighthearted place. I love you, I love you. I couldn’t do it

without you.

What soul can say for certain where her trail will

end, or upon which paths the sands of her life will blow? My life was one of

humble beginnings and yet I find myself at the point of scribing my name with

gods and murderers in the tombs of kings.

I have been given many titles in my life -

daughter, slave, and lover. Never have I held a child of my own in my arms. How

strange to think, then, she who has never borne life shall mother an entire

nation.

How I came to Egypt is not a mystery, in itself. I

was born in a coastal village in Thrace, near the shoreline fortress of

Perperek. We were often subject to slave raids from the neighboring Greeks and

Macedonians, the Spartans to the west, and the Persians across the cold salt

waters of the Sea of Marmara. All of them hungered for the strength of our

backs and the fire in our Thracian blood.

But, though we labored on the rocky slopes of the

Rhodopes Mountains, we loved as fiercely as we fought in homage to our honored

Dionysus, god of death, rebirth and of passion--my downfall.

Life in Perperek’s shadow was not easy. There were

those in our village who gained sustenance from the providence of the

ktístai

,

sacred priests in the temple. Fashioners of precious metals. And holy ones,

priestesses like my mother, a Bacchae, who crept the treacherous mountain paths

to worship the gods with wild beauty and song. Someday, I hoped I would be like

her. I dreamed of a time when I could live in leisure, with enough food to fill

my belly and, perhaps, lovely adornments for my body. Thracians have a love of

beauty, and I was no exception.

The village was filled with simple folk. We

tended, planted and gathered. But of all who toiled within the village, our warriors

were most revered. Warriors like my father. With pride I remember him, foremost

of those who fought for Perperek. His powerful arms. The precise color of his

red-gold hair, my legacy, shorn from his head in the warrior topknot. His

laughter. How much I loved him. But in my twelfth year, I set my feet upon a

course that would forever change us.

“What harm can there be in one last trip to the

temple before the storms come, Delus?” my mother asked. “There is talk in the

village of her.” She jerked her chin at me. “And of us.” She continued pulling

provisions from our dry storage for the evening meal.

“Sita, please. There is always the chatter of

crows in Perperek.” Milk of the gods, red and thick as blood, clotted my

father’s close-cropped beard. He motioned for her to refill the wineskin. “Let

the women talk. The Bacchae can wait. Perhaps in another year, we can spare

her.”

“The devotees of Dionysus will

not

wait. It

is time I took Doricha with me to the temple. She is nigh a woman and must earn

her place, as I once did. She is of an age that she can be taught the temple

diktat.”

My father smiled at me, his agate blue eyes

sparkling like sunlight on the waves of the sea. One large hand pawed the air

as he motioned for me to come forth. He seemed uncomfortable without the shaft

of his

sarisa

, his long spear.

“Have you memorized your mother’s teachings,

Dori?”

I nodded and ran to him. Twining my fingers into

the long tresses of his topknot, I marveled in the rich, warm protection of his

broad shoulders. His arms encircled me like bronze bands. The scent of roasting

goat wafted from the spit where my mother buried onions and garlic in the

tender meat, and I felt safe and as peaceful as I can remember being in my

life.

“You are a treasure, Doricha,” my father said. I

loved him for it. “I cannot let you go to the temples yet. Do you hate me for

denying you your birthright?”

“No, Papita.” And I didn’t.

His teeth flashed white against his ruddy skin as

I snuggled like a wolf kit into his lap. Though we were a spear’s point away to

starving as any in the village, my father saw a king’s ransom when he looked at

me.

I knew what starving was. Starving was thin,

patched wool cloth, and no meat. Starving meant freezing to death on the

mountainside at night, for lack of shelter and fire. True, we did not share the

luxuries of those who lived within the shoreline fortress of Perperek--but we

were not starving. Not quite yet. Once I was temple trained, my future would be

determined by my efforts to pay homage to the gods with my grace and beauty—or

the strength of my husband’s spear.

Still, I could not deny the warmth of my father’s

smile as he winked at me behind my mother’s back.

“The girl must take her place in the temple, as

others before her have done.” My mother wiped the fat grease from her hands

with a sharp, brittle movement. “Please, Delus. You must see the reason in

this. We can ill afford to anger them a second time.” She put away the scraps

from preparing our meal.

“I care not whom I anger. I am still your husband.

Or have you forgotten?” My father shook his head again and took another long

pull at the wineskin.

I burrowed further under the space beneath his

chin, tucking the skirt of my chiton around my knees. My mother’s lips

tightened and I confess I feared to see it, for it meant she was resolved to

have her way.

Do not mistake my heart in this. I loved my mother

as well as any daughter can, but in her eyes, I was first and foremost a

servant to Dionysus. It was heresy for me to refuse the path to temple service

when it was offered, when so many others had already been pressed into the

fold. Especially the daughter of a Bacchae. Yet to my mother, it seemed, I was

dissimilar to a king’s ransom as could be. I crouched there, safe and content

in my father’s arms, and glared at my mother’s back as she smoothed her hands

on her skirts, and turned to the chest containing her things.

“I have not forgotten, Delus,” she murmured. Her

movements were fluid and beautiful, as were those of all the Bacchae.

My father’s eyes were on her as she bustled around

our small hut. She knew it well, too. Maintaining her slight distance, she

uncoiled her bound hair until it fell in a shimmering crimson curtain in front

of her face, and picked up a carved wooden comb. Her limbs unfurled with canny

grace, mesmerizing to my eyes and to my father’s. With long strokes she brushed

her hair until it crackled with life, and the blue tattooed patterns on her

hands undulated in the firelight.

“Temple training has served us well, my love.” She

stared at him as her hands stroked up and down her exquisite silken locks. Her

voice was breathy and low. “And you are my husband. Still, we have a duty to

our people, Delus. We should not invite trouble where trouble does not dwell.”

I shifted in my father’s lap, uncertain of what

was to come next. His eyes never left my mother, but he took another long pull

at the wineskin. Some of the liquid dribbled out the side of his mouth and he

flicked a red-stained tongue to catch it. I was uneasy then, and acutely aware

of the smoking cook fire, my father’s unwashed but not unpleasant scent, and

the odor of soured grapes.

The firewood snapped, and I flinched. Father

laughed and embraced me even tighter. He crushed me against his barrel chest in

a bear-like embrace, while his rough whiskers tickled my cheek. “Very well,

Sita. You may take Doricha, but not until tomorrow. Tonight,” he smiled wide,

“we celebrate our victory over the Greeks!”

Mother’s cheeks were flushed. “Whist, Delus, for

shame! The battle has not yet begun, and will not until the moon shines bright

in the sky and the blood of Dionysus flows in your veins.”

My father’s laughter rattled the walls. “Think

you, they can best a Thracian? Come to me, Sita, that I may impress you with

the strength of my spear.”

My mother ran to him, her lovely face alight with

inner fire. She giggled like a young girl, sweeping herbs from the table onto

the floor in her haste. Father nudged me out of his lap to make room for her. I

huddled on the floor by their feet, forgotten, and busied myself with

separating the plants, until their soft laughter ceased. They rose and drew the

goatskin curtain back from the sleeping quarters. Father grabbed the wine.

“Doricha, go and fetch some water from the well. And

stay clear of the trees. There are Greeks about.” Father’s voice thickened with

so much wine in him. A glance revealed naught of my mother save her long,

slender limbs disappearing under the animal hides in the sleeping alcove.

I sighed, and grabbed the heavy wooden bucket from

its customary place, feeling surly from his oft repeated warning not to venture

into the unknown cypress groves at night. I’d never penetrated the thick trees

that hid us from the west, but kept always to the low bracken on the forest’s

edge as I made my way to the well.

Life in our village was ever solitary and

unchanging. In my few years of life, I’d busied myself with toiling at

gathering herbs or tending the small animals, as the villagers eschewed playing

with the daughter of a Bacchae. Now, here I was poised on the precipice of

womanhood. The pale moon hung just above the forest line, as I slipped from our

hut with a strange tight knot forming in the pit of my stomach, feeling both

loved and unwanted at the same time. In the twelve winters I lived in

Perperek’s shadow, I had yet to disobey my father, but tonight, with the soft

mewlings of my mother erupting from our tiny hut, I felt a burning in my middle

I could not explain.

With tears pricking my eyes, I entered the bower

of midnight cypress just beyond our village. I wandered through the silent

trees and scuffed up the dried fallen leaves that filled the air with a musty

scent of decay.

An image of my father’s face flashed before my

eyes and I hurled the bucket into the trees. I tromped further into the grove,

taking no pains to be quiet. So, there were Greeks about? Well, they never came

so close to our village and our men would raise the alarm if they did. Besides,

my father was so enthralled with my mother’s company, he would not even notice

if I was taken. Such were my thoughts and I am heartily sorry for them now.

Many times I have wished to recapture that moment

when first I chose to leave the safety of the path, but I was a child then and

had not a woman’s experience to make me wary.

I walked on in a night-blind stupor, until the

crack of a twig pierced my solitude. With a start, I realized I was much

further into the forest than I’d thought. Perhaps, too far. Where were my

bucket and the path that would lead me home?

I wandered for what seemed hours, thinking one

way, and then the next was the path I sought. Scuttling blindly through the

underbrush, rising panic beat a steady tattoo in my chest. Surely my father

would search for me? His concern over my tardiness would steal him from my

mother’s embrace, I thought. He loved me. He would come.

I waited, but he did not appear.

Unable to find my way home, I climbed the bough of

the nearest tree and sought refuge from the cold night and the prowling beasts

that preyed on human flesh. Perhaps in the morning light I would recognize the

way back to the village. Insects and other creatures of the forest clicked and

chirruped. Long moments passed, how many I cannot say, whilst I shivered and

sniffled into my damp woolen chiton, cursing the passion between the two people

I loved most in this world.

At once, I heard a strange noise, like a scuffle

in the underbrush, and held my breath. Who was about? Could it be my father? Then

another thudding hiss.

At the soft jangle of unsheathed metal, I thought

with a child’s hope it might be my father come to claim me. Slipping from my

perch, I crept toward the footsteps and whispers that emanated from the forest

grove.

“

Papita

?” I called softly.

Closer I moved toward the sounds and closer still,

until at last, I came upon a sight that burnt itself behind my eyes forever. It

was not one man, but many gathered in the woods that night.

The Greeks had come.

A group of twenty men from the village, men I had

known most of my life, burst from the trees. Their faces were painted with mud

and gore. They erupted in a wild frenzy, and howled like wild beasts as they

fought a horde of armored Grecian invaders. The odor of blood and filth

infiltrated the night air.

I froze.

Blood poured like red wine from split skin and

bones. Someone bellowed behind me and I scrambled behind the nearest tree trunk

and covered my mouth with my hands to stifle a scream as the sounds of battle

grew nearer. I did not want to look, but somewhere my father might be fighting

nearby. Keeping my back safely against the cypress trunk, I peered through the

dark at the carnage.

Some men carried swords, others their long spears,

but nowhere did I see my own father’s sarisa. All sounds froze in my ears, and

feeling fled from my limbs. I heard only my own ragged breathing as I watched

men screaming, hacking and dying.

Please

, I begged the unhearing gods,

as if my entreaty could move their immortal hearts.

Let him be home

enjoying the embrace of my mother’s body. Spare him

.

But Bendis, Huntress of the Earth, and Dionysus

turned their cruel faces away from me.

My father entered the starlit clearing. He towered

over the Greek invaders. The gore of battle covered his ruddy skin. With a wild

cry, he thrust his

sarisa

into the neck of the nearest Greek. A

spout of night-black crimson spattered his face and tunic, transforming him to

a living specter of Death.

He bared his teeth and growled a challenge. Two

Greeks attacked, swinging their swords and hacking at him. Father dispatched

them at once, his movements strong and sure. Another Greek, and yet another

succumbed to the tip of his spear. He was a fearsome sight. The men from our

village cheered as the grove began to clear of invaders. Bracing his stained

leather boots against the helm of a fallen raider, Father jerked his

sarisa

free and leapt out of the reach of the next invader. He veered into the worst

of the battle and spun. There, he jabbed with the tip of his long spear, to

worry the men who followed him. I’d never been so afraid, nor so proud. My

father, Delus, the pride of Perperek.